I

It’s fun to imagine what the devoutly digressive Swiss writer Robert Walser (1878–1956) would have made of the term “plot twist.” His stories generate so many whimsical offshoots that the twists themselves become the plot, or rather a series of plots that are gleefully announced and abruptly dropped, sometimes in the course of a single page. He favored, particularly in the wonderful novella The Walk, the structure of a ramble, which is, like many things in Walser, a contradiction, because rambles generally do not have structure. In a single short paragraph early in The Walk, the strolling narrator takes note of a bookseller, a bakery, a parson, a chemist on a bicycle, a doctor, a “bric-a-brac vendor,” and a group of children at play. “Let them be unrestrained as they are, for age, alas, will one day, soon enough, terrify and bridle them,” he muses, invoking, in classic Walser fashion, both youthful euphoria and the threat of soul-crushing adulthood in one fell swoop. He then ducks into a bookstore and offends the owner (“Uncultivated, ignorant man!” the bookseller shouts), and briefly visits a bank, where he learns that a group of philanthropic women have awarded him one thousand francs for no apparent reason. We are at this point only seven pages in.

One of the many remarkable qualities of Walser’s writing is that it holds together so well, even as it delights in its own recklessness. His style is at once unmistakable and hard to pin down. W. G. Sebald, another writer who found inspiration while walking (although he favored a more contemplative pace), called Walser a “clairvoyant of the small.” This is true—as time went on, even Walser’s handwriting became tiny. But his work is also spacious, rangy, and excitable, rushing along as if there’s a new discovery to be found at every turn. His narrators’ mental states are wiley and difficult to locate. The tone of the books tends to be erratic, evading the adjectives that might appear, for a moment, capable of capturing it.

Consider Walser’s novel Jakob von Gunten, narrated by a teenage runaway who has enrolled at a school for servants called the Benjamenta Institute, whose perspective and opinions dip and soar with the dramatic flair of a trapeze act. Jakob proclaims the importance of selflessness: “I know what a pupil at the Benjamenta Institute is, it’s obvious. Such a pupil is a good round zero, nothing more.” He asserts, in rhetoric that borders on the hyperbolic, the virtues of obedience. “To comply, that is much more refined, much more than thinking,” Jakob remarks. “If one thinks, one resists, and that is always so ugly and ruinous to things.” All of which would make him sound like a poster boy for servitude, except for the fact that he is just as often given to outbursts such as this:

“One must learn to dominate situations. I know excellently well how to throw my head back, as if I were outraged by something, no, only surprised by it. I look around, as if to say: ‘What’s this? What did you say? Is this a madhouse?’ It works. I have also acquired a bearing in the Benjamenta Institute. Oh, I sometimes feel that it’s within my power to play with the world and all things in it just as I please.”

Jakob is obsequious in one paragraph, subversive in the next. Often he is both things at once. His deference to the rules itself conceals a peculiar freedom, a refusal to compete, all the better to pursue his fantasies on the sly and without interruption: “Something great and audacious must happen in secrecy and silence, or it perishes and falls away, and the fire that was awakened dies again.” Even at his most compliant, Jakob celebrates his own subordination with such grandiosity that he approaches an infringement of the Benjamenta’s code, which forbids cheekiness.

It is difficult to describe a character like Jakob without placing him at odds with himself—is he an earnest pupil or a fount of mockery, a benevolent subordinate or a disaster about to happen? But Walser himself shows little interest resolving or even acknowledging the inconsistencies he euphorically offers up. His narrators pursue every notion and observation with equal interest. The ideas advanced in his monologues seem to take on lives of their own, grabbing the mic, running astray, and asserting themselves. Walser isn’t unique in revealing his narrators’ contradictions. But his treatment of those contradictions puts him in a unique class. With perhaps the exception of Jane Bowles and Gertrude Stein, it’s hard to think of a writer who can present a character’s paratactical ideas as gently and radically as Walser does. In the hands of another author, Jakob would most likely feel subservient and yet rebellious; the two feelings would inflect one another, and the contradiction would become a subject of inquiry and nuance. In Walser, Jakob feels both of these things without the “and yet.” His positions oppose one another, but they do not cancel each other out. He honors both. Such a disjunctive approach should result in a mess, but Walser’s eccentric enthusiasm provides a sense of cohesion and holds the reader’s attention, even as the narratives grow increasingly erratic. This is in part why he can slip from irrational exuberance to depressive defeat—and, remarkably, from one verb tense to another—without apology, explanation, or even transition.

The momentum of Walser’s prose delivers many local pleasures, generating unhinged observations at a rapid clip. Meanwhile, a more general sense of mystery and depth builds. This comes as a surprise, because at first glance, his stories do not linger over insights, or delve into his characters’ psychology, or pause to ponder complexities in motive. But the way his narrators raise and abandon topics without integrating them into the larger story results in a strange, layered effect. As readers, we pass through these ideas as if through rooms on a very unpredictable house tour. Walser’s design relies on a preservation of and an effortless, unpredictable navigation among these exceedingly various spaces.

II

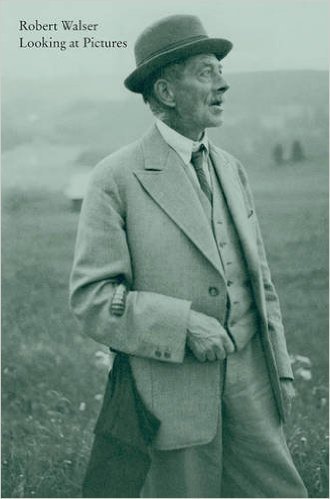

Walser’s delightfully kinetic storytelling style is on full display in Looking at Pictures, a recently published collection of short fiction and essays about art, translated by Susan Bernofsky, Christopher Middleton, and Lydia Davis. Here, we get to see how Walser, an author who consistently resists framework, writes about painting, which typically sits inside a frame. The ostensible subjects are artworks by van Gogh, Fragonard, Hodler, Bruegel, Cézanne, and others, and there are, occasionally, wonderful moments of descriptive writing. Of Aubrey Beardsley, Walser writes: “It may be that never before has an illustrator reproduced the flickering of a candle in so candle-like a manner, so flickery.” Staring at van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne, 1889, he notes “a wonderful patch of red that is delightfully in flux.” But as these descriptions suggest, with their flicker and flux, Walser does not offer an authoritative or objective representation of the artworks but an account of his own personal and deeply idiosyncratic interactions with them. He wrote about art as a “rapporteur,” dashing “through the streets . . . entering premises in which imposing works of art are on display, so as to try my hand at them journalistically.” The paintings he writes about are therefore various in style. What most of them have in common is that they set the author’s imagination in motion, inspiring him to concoct elaborate dramas that extend far beyond the confines of the scenes portrayed. The paintings he writes about all tend to spill outside of their boundaries. Looking at a wintery scene by Hodler, Walser feels compelled to put his hands in his pockets to keep them warm.

Many of the essays project audacious fantasies onto a particular painting. After offering some vague observations about the appearance of the peasant woman in van Gogh’s L’Arlésienne (“She wears the sort of skirt one sees all the time”), Walser’s description takes a hallucinatory turn: “The woman suddenly began speaking about her life,” telling him of her childhood, her parents, and school. In “Catastrophe,” probably about Albert Bierstadt’s The Burning Ship, ca. 1871, the author, never content to simply look at a picture, writes as if he has boarded the sinking ship himself. There, he finds two lovers who, in Walser’s increasingly unhinged fantasia, acquire an ornate back story: They have betrayed one another during the voyage but are now, facing disaster, reunited. They must all dive into the water, where they will drown. The final line is: “How our imaginations can run away with us!”

Other pieces here find traction in anecdotes that bear only a tangential relation to the artwork at hand. Lucas Cranach’s Apollo and Diana, 1530, inspires Walser to recall living in an apartment in Thun, where his landlord removed a reproduction of the painting that he had tacked to the wall, presumably because she was offended by the nudity. (He writes a “brash epistle,” but there is no rancor here; the landlady is soon, in a denouement that begs for psychoanalytic gloss, offering to mend Walser’s torn trousers.) An essay that’s supposed to be about Belgian art instead finds Walser rhapsodizing about a coffee shop, recalling a dream, and feeling “enlivened” by memories of a woman who has moved to the US. “How grateful I am,” he remarks, “that she once, with marvelous dignity, gave me a proper ‘dressing down’ outside a department store. ‘Dressing down’ is being used here to describe a certain breaking off of relations or rebuff.”

Throughout, Walser’s prose slips among a variety of tempos, registers, and tones. He is by turns lackadaisical (“There is no elegance without a certain nonchalance”) and enraptured (“Drafting a prose piece puts me in a devotional frame of mind”). He is allergic to playing the role of an authority (“Knowing little about him” are the first words of his essay about Watteau). But in freeing himself from the constraints of expertise, he is also able to throw himself, almost authoritatively, behind his eccentric interpretations. “Can she not have had a lover, and known joy, and many sorrows?” he asks about the woman in L’Arlésienne, and then abandons the question to offer, quite confidently, details about her everyday life. “She listened to the ringing of bells, and with her eyes perceived the beauty of branches in blossom.”

As in much of his work, Walser reveals a deep affection for multi-layered narratives, which provide him multiple entrances to the subject at hand. The author recalls coming across a reproduction of Hodler’s The Beech Forest, 1885, hanging in the window of a bookstore (many of the pieces here mention reproductions, which themselves suggest how a painting can exceed its own framework). This reminds him of a party he attended long ago, where he saw the original artwork hanging in a maid’s room. The piece becomes, in effect, a review not of the painting itself but of a memory of the painting. Walser’s imaginative élan allows him to burrow deep, but he is just as fond of an exit strategy. An essay on Bruegel concludes: “Beautiful women adorn the promenade with their presence, and still I sit here writing?”

Walser is rarely content to sit in a single time frame, or in a single space. His reflections on Fragonard’s The Stolen Kiss, 1786, open by invoking a modernity that lay far ahead of the scene portrayed: “Railroads didn’t exist yet, and the niceties of central heating had not yet been worked out.” At the moment the (imagined) lovers of The Burning Ship jump into the water, the author imagines concomitant scenes on the mainland, featuring people who have no idea that the ocean tragedy is taking place: “At this very hour, perhaps, a conscientious thinker in a reclusively charming room on the mainland was composing an essay that would usher in reforms, and at the very moment this serious occurrence was taking place out on the water, a dandy was sitting perhaps in a barbershop, being shaved by zealousness incarnate.”

Paradoxical to the end, Walser’s work can also reverse the process, finding multiple worlds in minutiae. As Sebald noted, he saw multitudes in small things—and even, as Jakob von Gunten suggests, in tight spaces. Walser’s “Thoughts on Cézanne,” which closes Looking at Pictures, admires the painter’s gift for finding life in small, ordinary objects: “Even this tablecloth has its own peculiar soul.” He ponders Cézanne’s late-life reclusiveness, and imagines the artist’s wife, Marie-Hortense, urging him to leave the valley where they lived, to travel and see more of the world. In Walser’s version of events, Marie-Hortense packs Cézanne’s bags, but he ultimately refuses to leave. The author respects the decision, pointing out that enclosures can contain more possibilities than a world without boundaries: “My gist is that a region, for instance, becomes bigger and richer in a surround of mountains.”

From Jakob von Gunten to “A Painter,” the story of an artist and his benefactress, Walser’s work suggests a longstanding fascination with and horror of entrapment. Later in life, Walser became devoted to his own enclosure. In 1929, after suicide attempts, bouts of hallucinations, and a mental breakdown, he checked himself into a psychiatric facility in Bern. In 1933 he moved to another asylum, where he would remain until his death. A sanitorium, you might say, is the ultimate frame, certainly more confining than a mountain range. Perhaps this is why Walser stopped writing during his institutionalization—he no longer felt (or no longer wanted to feel) the freedom that allowed him to write so expansively. Susan Bernofsky’s biography, reportedly in the works, will surely shed more light on this and other phases of his life. One question I have is: Was Walser’s life in the sanatorium anything like Jakob’s life at the Benjamenta? Perhaps, insofar as Walser was, like Jakob, still able to stray, at least a bit. He was allowed to wander the grounds. He died on Christmas Day, 1956. While taking a walk, of course.

Michael Miller is an editor at Bookforum.