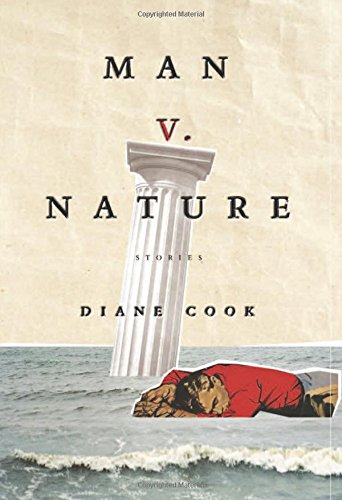

Diane Cook’s debut collection, Man V. Nature, strikes a disarming balance between quirk and claustrophobic sadness. In the opening story, a woman is removed from the house she shared with her late husband and taken to a shelter for widows and divorcées that, with its barbwire fences, is essentially a prison. Forced to take part in “moving on” seminars, the residents are denied even private expression of their grief as they wait to be assigned a new husband. In form, “Moving On” could be by one of Cook’s fellow social surrealists: Aimee Bender, George Saunders, or Steven Millhauser, all clear influences. Yet the strangeness of those writers has always offered a kind of security. Any critique provided by their alternative worlds is blunted by offbeat irony, casual magic, and a fashionably twee sense of the absurd, the approach more waggish courtier than avant-garde. Cook, on the other hand, carefully amputates all superficial faith in human nature. In doing so, she has written a collection that reads as more realistic than anything lately called realism.

Cook came of age in the hellacious 2000s, and she is unflinching in illustrating what our current condition feels like. In today’s political and social climate, the premise of “Moving On” is depressingly plausible. I know of no real-life junior executives being vivisected in corporate stairwells by a rampaging monster, as in “It’s Coming,” but the fictional execs, much like the young American inheritors of mass debt and unemployment, have to hear a whole lot about how it’s their own fault as they’re being ripped to shreds. Best of the purely allegorical pieces is “The Not-Needed Forest,” in which children whose future contributions have been preemptively deemed negligible are flushed down an enormous chute to an isolated wilderness. Here, Cook compresses a Lord of the Flies–type descent into barbarism into twenty pages simply by acknowledging that being found extraneous in the eyes of culture and the state is no longer merely something to fear; we ought to expect it.

This, then, is the Nature of the title. We should be less afraid of avalanches, earthquakes, volcanoes, and white water rapids than biopolitics. Cook’s breakthrough is in treating oppressive man-made constructions like beauty, marriage, and motherhood exactly as we have been trained to think of them: a priori realities beyond any question or doubt. The recent post-apocalyptic novels by Edan Lepucki, Laura Van Den Berg, and Emily St. John Mandel (to name a few of the best) are fantasies by comparison, exercises in imagining worlds just slightly worse than ours. It’s telling that Cook’s women don’t find their position in the world much altered by its having ended. One of several tragically funny wife-stories in the collection, “Marrying Up,” set after “the world got bad,” presents a collapsed cityscape waiting outside the apartment, an unspecified emergency state where only the strong second husband (the first was too weak) with his “violent kind of love” has the right of passage. For the good of the family, he leaves his weakening wife to nurse herself dry. (That doesn’t sound very funny. I promise it is.)

“The Way the End of Days Should Be” depicts an even more vivid doomsday. A wealthy man watches a flood from the elevated comfort of his sprawling estate, and presumes that the social contracts that so far have safeguarded his fortunes will outlive the apocalypse. It’s inconceivable to him that Gary, the man he’s rescued and sheltered, won’t be grateful or endlessly generous with his free labor. Having long conflated capitalism with human nature, the landowner refuses to help those marooned neighbors who can’t help themselves and is shocked when they begin to rally against him. How could this mutiny happen, when he was so unselfish with his liquor cabinet, so happy to instruct Gary, who leads the insurgent throng, in the wearing of French cuffs and silk undergarments? Earlier, thinking of the good life he enjoys as servitor, Gary had quibbled with his master over the definition of homelessness. The landowner gives his account of the argument:

I don’t know what he means. “Don’t be absurd,” I say. . . . Homelessness is a term of destitution. We’re not hanging out of windows, waving blankets; we’re not trod upon by soggy feet like my neighbor. But undeniably we are experiencing a lack. I respond, “Friend, we are worldless.” I let my new word linger.

The fatal conflation of the particular with the universal is a running theme in Cook’s work; having a home isn’t the same as being at home in the world. In the title story, it takes being adrift on a fishing boat for three men with scant hope of rescue to realize how little difference their lives make, to each other or anybody or just in general. “He’d rather drown,” one of them thinks, ”than stay in a boat with himself.” Even being happy—temporarily, of course—has a high price, as the couple in “The Mast Year” discover when their good fortune attracts a freebooting camp of seeming nomads who horn in on their romance, eating their food and sleeping under the dining-room table.

These might count as classic epiphany stories, but the only secret they reveal is that reality isn’t what you make it—it’s what other people put you through. Women have known this for centuries, even as they were being trained from birth to accept subjugation, objectification, and dependency as the “natural” order. Man V. Nature is split between women who struggle to conform to what their husbands and lovers demand and those who, ever so meekly, take up arms against the patriarchy. Or, in “Somebody’s Baby, ” against the man who waits in the front yard, sneaks in through the windows, and steals the babies. This is Cook at her bleakest and most whimsical, as the response to the baby-snatcher’s thefts point up the impossibility of expecting sympathy from other people:

There’s nothing you can do, her neighbors reminded her as she grieved. A few had stopped by bearing casseroles, homemade jams. You’ll get past this, and then you’ll have another, they said. But he’ll just take that one, she said. Maybe not, they exclaimed hopefully. Sometimes he only takes one!

Heartbreakers like “Girl On Girl” (an overweight girl begs her friends to trample her into a more pleasing shape) or “Flotsam” (a woman arranges children’s clothes from the laundry into the shape of the kid she isn’t allowed to want) ask the questions: Is there any unselfish act in the world, any relationship that is not somehow one-sided? Can we really know or care about anyone else or only about ourselves?

Man V. Nature shows us what very few books can—a “natural” world we recognize, but in other terms. We connect to Cook’s representation of life for the same reason that we are able to get through our experience of our own. Real life is not only terrible, it is comically terrible, well beyond the most bizarre farce. Realism will survive as long as somebody’s still bothering to survive to tell the tale. But if Man V. Nature is any indication, its new form will be somewhere between the sugarcoating of genre and the cold comfort of stylistic whimsy, taking the best of both and converting the rest to brutal new terms. Being partial to the trappings of imaginary tales—faerie stories with the faeries taken out—doesn’t mean you can’t tell the difference between falsehood and what we still recognize, by any name and however hard it is to swallow, as the truth. The most honest fiction in an era of certain oblivion will be that which dares to say: “It wasn’t a good life. But it was a life.”

J. W. McCormack has published in the New Inquiry, the Brooklyn Rail, Tin House, N1FR, Publisher’s Weekly, and Conjunctions, where he is a senior editor. He teaches at Columbia University.