Partway through Sophia Shalmiyev’s new memoir, Mother Winter, the author returns to Russia in an attempt to find her mother, a woman who has been absent most of her life. Shalmiyev imagines that the journey will be beautiful: “I would book the trip during the famous white nights in June, when the bridges part over the canals and it is dusk at four in the morning, the city actually not being able to sleep so people become possessed; they make out on every corner and leave their spouses for anyone who winks at them. I wanted my three-note, sleepy, leveled and depressed but loyal boyfriend to wake up in Russia and never pass out on me again.” Shalmiyev’s impatient hope feels familiar. Many of us attempt to preorder the turning points in our lives, planning a momentous event to crack our story open.

But as is often the case with this kind of planning, the trip turns out to be one frustration after another. “The glory of the white nights never materialized, because I was mostly paralyzed with dread and feelings of incompetence for not knowing how to find my mother.” She fails not only at this, but also at remembering the locations of airports, making connecting flights, waking up before noon once she arrives in St. Petersburg, and finding any information about her mother from government offices, city archives, family friends, or even by visiting what was once was her grandmother’s apartment. She fails to reignite her relationship with her boyfriend, too. Her story never cracks open. Shalmiyev’s life remains fragmented and incoherent—something with too many sharp edges to hold.

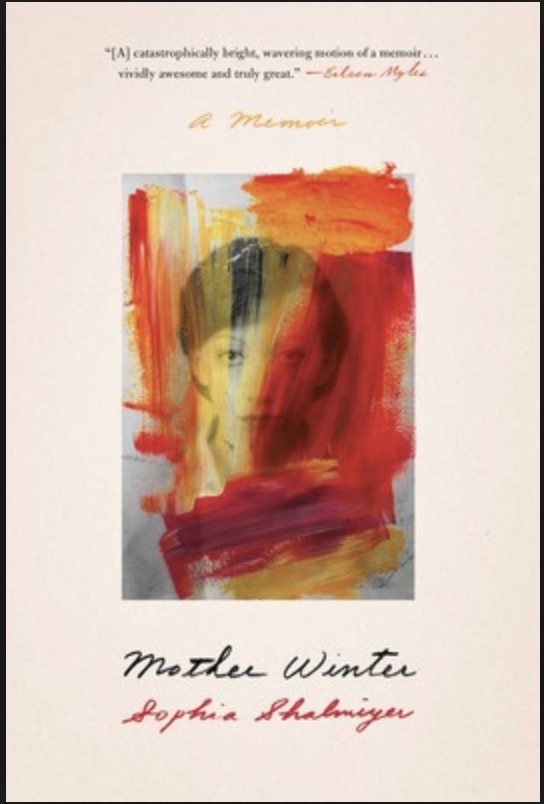

Shalmiyev builds her compelling new book out of those fragments. She tells the story of her life to date, structuring it around her attempts to make sense of her mother’s absence. Shalmiyev’s mother and father divorced in her early childhood in part because of her mother’s alcoholism; shortly after, in 1990, she and her father left Russia. They eventually wound up in Brooklyn, joined by Shalmiyev’s young stepmother. The events of the story are relatively small, and relatively straightforward, set against grand geopolitical events: As the Soviet Union collapses and the Cold War ends, Shalmiyev grows up, goes to college, and eventually marries and has a family of her own.

Shalmiyev renders motherhood and childbirth in graphically—almost confrontationally—physical terms. The story of her life is the story of a body, often violent, always leaking and wanting and making demands. In one memorable passage, she compares her post-childbirth body to her childhood bedwetting: “My womb is shrinking and draining itself of the blood that cushioned my daughter onto witch hazel–soaked pads I intermittently grab from the freezer. My pelvic floor muscles inverting back in like the rope of a tire swing pulled over a tree branch. The bed is a swamp again.” For Shalmiyev, motherhood may be an inheritance passed down from woman to woman, but so is the sexual, grotesque body; the two, she reminds us, are one and the same. “That body will make me think of her,” she writes, “how it was given to me through her lust and labor pain. . . . I will ache at the source. And I’ll try to see her. I will give birth twice in lieu of going back again and again to my first home.”

In her twenties, Shalmiyev works as an art therapist at a domestic violence shelter. Her description of the women she works with could easily apply to her own searching: “They needed the past reinterpreted for them so that it fit, sequentially, contained back into their heads, heads they banged on the walls, wailing, acting out, begging for a story with a beginning, middle, and end.” Shalmiyev’s protagonist grasps for this beginning, middle, and end in Mother Winter; Shalmiyev the author, however, knows that in real life these structures rarely appear. Her narrative is impressionistic, full of digressions on a mountain of topics including female artists, famous mothers, Russian history, the 1990s, the Pacific Northwest music scene, sex work, hospitals, child-rearing, Anaïs Nin’s sex life, friendship, marriage, and Cat Marnell. These digressions can be frustrating, perhaps intentionally so. That’s part of Shalmiyev’s point: Nothing hangs together. The search is all there is.

Shalmiyev is not particularly interested in “healing” or in conclusions. Throughout her story, she seeks surrogate mothers, both real and imaginary. These are often female authors, particularly ones who focus on the body, sex, and violence, from Nin to Kathy Acker to Valerie Solanas. While these writers can’t give her a guide to motherhood, they do allow her to place herself outside the expectations for how to tell its story. They point her away from “beginning, middle, and end” and back toward angry, unanswerable questions. The book becomes a refusal to make peace with her mother—either the real woman or the ghost.

During her failed trip to Russia, Shalmiyev ends up at the Hermitage. In an attic where restorations are being done, she sees that “the restoration could only attempt to fix the piece up to a certain point, about the time one would begin to suspect the onset of an unacceptable kind of ruin. The larger, understood decay had to be respected and drawn around.” The restorer does not touch or sculpt the damage, but only draws around it. Likewise, Shalmiyev will often relate a wrenching incident from her past—her father’s physical abuse, for instance—somewhat flatly, and then never return to it. In memoirs, trauma usually comes with a lesson; out of pieces, we’re supposed to assemble a workable whole. But damage, sculpted into a story, is still damage. Shalmiyev refuses to arrange it into something comforting.

Helena Fitzgerald’s writing has appeared in the New Inquiry, Catapult, the New Republic, and other publications.