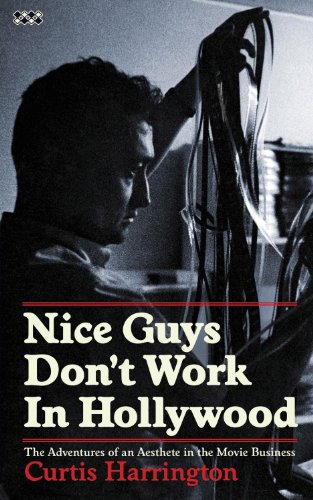

“Who is Curtis Harrington, and what other films has he made?” This was asked by an audience member after a screening of Harrington’s What’s the Matter with Helen? , a drolly macabre thriller about two middle-aged women operating a dance school in ’30s Los Angeles. In Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood, Harrington sets down this query as evidence of his fated obscurity—though the filmmaker’s anecdote-rich posthumously published autobiography goes some ways toward answering both questions, and will hopefully earn his work recognition from a new audience.

It may seem absurd that the director of fare like Queen of Blood or Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell should tag himself with a highfalutin word like “aesthete,” more associated with Harold Acton’s Memoirs, but Harrington is a fount of erudition, accumulated through a singularly free-ranging life and career. Before his death in 2007, he modestly set down the facts of both for the historical record, leaving it to Dennis Bartok’s introduction to make the grand claims: “I think possibly David Lynch is the only other director who made the transition from avant-garde cinema to mainstream as successfully as Curtis,” Bartok writes, further asserting that Harrington was “one of the first American directors to start as a film critic and scholar and later become a director himself.”

Like Lynch’s, Harrington’s background is pure wholesome Americana. Harrington was born to transplanted Midwesterners in Los Angeles, 1926. He spent his first nine years there—the same period in which Helen? is set—until the depression drove his attorney father to move the family and try his luck in Beaumont, California, a “small town on the road to Palm Springs” that “might just as well have been Winesburg, Ohio, or Kings Row.” Recounting his boyhood in small-town Beaumont, Harrington gives the impression of happy formative years, a budding aesthete’s youth divided between the library and the movie theater. The author has only good words for his “kindly, supportive” parents, and expresses no feelings of guilt or self-reproach over the pubescent discovery of his same-sex desires, even while recalling the unusually secretive measures necessary to satisfy them, such as rendezvousing with a boy who worked as a night watchman in local funeral parlor.

Such clandestine activity contributed to Harrington’s sense of small town America’s double-life, divided between appearances and what transpired behind closed doors—Winesburg, Ohio, indeed. (Years later, working as an assistant to producer Jerry Wald at Fox, Harrington would collaborate on the script to 1957’s seamy exposé Peyton Place.) Alongside memories of Beaumont’s local lesbian and madwoman, Harrington recalls learning tricks from one Mr. Berman, a jeweler who moonlighted as an amateur magician, who later moved away. “A few months later,” Harrington concludes in his dry, unadorned style, “we read in the papers that Mr. Berman has been shot to death by his son for beating his mother.”

Having found outlet for his mordant imagination at age fourteen by making an amateur 8-mm film adaptation of Poe’s House of Usher, Harrington eventually made his way from Beaumont to USC film school where, on his own time, he produced some of the first avant-garde films on the West Coast. (These have just been released on DVD by Flicker Alley as The Curtis Harrington Short Film Collection.) Harrington was working along parallel lines with classmate and budding occultist Kenneth Anglemeyer (later Kenneth Anger), who, along with other new influences, would stoke Harrington’s “growing curiosity about the esoteric—that which lies hidden beneath the surface of life.”

After first pursuing life to New York, in 1950 Harrington followed Anger to Paris and the Cinémathèque Française. This movie-lover’s mecca was soon to be the incubator of the French New Wave, but Harrington’s circle was by no means limited to cinephiles. On either side of the Atlantic we get glimpses of such varied figures as Anaïs Nin, James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, Julien Green, and Robert Bresson. Unfortunately, many of Harrington’s sketches lack the telling detail to make them stand out—perhaps because his death came before finishing touches could be added.

Harrington would miss the crest of the New Wave, as poverty necessitated a return to native soil. Once home we follow Harrington through his Hollywood apprenticeship with Wald and the shooting of his first narrative feature, Night Tide, a Jean Cocteau and Val Lewton-inflected B-movie shot on the seedy waterfront of Venice Beach in 1960, in which a young sailor on shore leave, played by Dennis Hopper, begins to suspect that the sideshow mermaid he’s courting is in fact a fatal siren. Superstition didn’t stop at the screenplay, for Harrington’s landlady augers ill omens for the Mercury retrograde start-date of the shoot. And the influence of the stars and the influence of movie stars will henceforth be the recurring subjects of Harrington’s book. (“Cinema,” we learn, “is under the planet of illusion, Neptune…”)

Harrington’s peak period as a feature filmmaker came from the late-’60s to the mid-’70s, when he worked largely in the “Grand Dame Guignol” sub-genre popularized by Robert Aldrich’s 1962 Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? This allowed Harrington to frequently cast actresses remembered from childhood, then in middle-age or past: Shelley Winters (twice), Simone Signoret, Gale Sondergaard, Gloria Swanson, Joan Blondell, Barbara Stanwyck, and Ann Sothern—whose character in 1973’s The Killing Kind was inspired by another of the harridan landladies who so fascinated him.

While each actress is discussed in turn during the film-by-film tour of Harrington’s directorial career, those led to expect a steady stream of calumny from the book’s title will be disappointed. Personal peccadilloes and minor on-set mutinies are duly set down, but everyone is evaluated in the final balance for the degree to which they helped or harmed the production at hand, usually generously. It doesn’t get much dishier than identifying meddling costumer Joel Schumacher as “later a well-known Hollywood director of meretricious films,” though TV execs—Harrington did a string of TV movies through the ’70s, as well as series work—come in for particular scorn. “How the network executives hated the unconventional and the unexpected, how they loved their comfortable little groove of mediocrity,” Harrington opines, after noting the trouble he had casting his “favorite bogeyman,” character actor Timothy Carey, who’d overzealously attacked another performer while shooting a scene in an episode of Baretta.

Nice Guys Don’t Work in Hollywood is not, however, just a string of who’s-whos swanning through the author’s purview. The great and laurel-strewn share the stage with the humbler exotics of Hollywood Babylon—those landladies and busybody spinsters, an unhinged studio secretary, a dance studio proprietor-cum-producer trying to “fix up” his Brooklyn hermaphrodite buddy, and Cameron Parsons, the widow of a rocket scientist and high-ranking Satanist. Even Harrington’s time at Universal Studios is given the aspect of a dark fairy tale, for this is the era of the MCA takeover, when a warlock named Lew Wasserman ran his fiefdom from what his servants on the lot called the “Black Tower.” When Harrington writes about showbiz, as when he writes of the everyday, he finds it touched with an aspect of mystery and Magick.

For example: The bizarre twin cults of Shirley Temple and radio evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson form the backdrop of Helen? The film doesn’t deal in nostalgia, though, but rather shows pop culture as a space in which the repressed and forbidden knowledge of an era can, in a distorted form, be safely expressed. The return of the repressed is at the center of Harrington’s best work: See Sothern’s monstrous matriarch fatally doting on Jon Savage in The Killing Kind, Anthony Perkins and Julie Harris’s brother-sister cage match in ABC Movie of the Week How Awful About Allan (1970), or Winters clinging to her mummified daughter after death in Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (1971). While not the sort of fare likely to attract critical raves in their own time, these are films that combine the smothering domestic detail that one finds in one of Georges Simenon’s “hard” novels with tenebrous atmosphere and a camp humor that owed much to the work of Bride of Frankenstein director James Whale, whose 1932 The Old Dark House Harrington was instrumental in saving.

Harrington’s style, as well as his understanding of pop culture’s function as a national subconscious, was informed by his film-historical acumen; included as an Appendix is his “An Index to the Films of Josef von Sternberg,” written during a stint as a Paramount message boy, in which Harrington praises the director of The Scarlet Empress for his “pungent humor,” “feeling for the pictorial value of the sordid,” “dark, sensuous compositions,” and “intense awareness of light and shadow, as the very substance of cinema.” The work of a very sophisticated twenty-two-year-old, this “Index” also shows that from an early age, Harrington was plotting the course to be taken by his own esoteric art, which we now have a valuable new tool to the decoding of.

Nick Pinkerton is a Brooklyn-based film critic who regularly contributes to Sight & Sound Magazine, ArtForum, and SundanceNOW.