In 2012, the British magazine Sight and Sound polled the film critics of the world to name “the best picture ever made,” and the result, that year, was Hitchcock’s Vertigo. David Thomson has described the film as a “piercing dream,” but, possibly challenging common sense, I am not going to explicate the full plot of the film at length here, or make a claim for it, in case the reader has never seen it. I will simply say that in this movie, a detective is asked to follow a beautiful, glamorous woman who is thought to be suicidal. Notice that the plot really begins with a request moment based on friendship between the two men: the woman’s husband has asked the detective to please follow his wife and protect her from harm. This detective soon falls in love with the beautiful suicidal wife. When the detective, played by James Stewart, is apparently unable to prevent the woman’s suicide, he falls into terrible, disabling guilt—he goes crazy for a while—and when he recovers, he finds another woman, a retail clerk, on the street in San Francisco, a woman who maybe resembles his lost love, whereupon he does his best to persuade this woman, Judy Barton (in a second request moment), to dress up and do her hair so that she will resemble the dead, lost woman he could not save. Two request moments shape the plot. Once Judy Barton does what the detective has asked her to do, she, miraculously, confoundingly, looks exactly like the woman who died—not similar to her, but exactly like her.

This synopsis includes only what happens on the surface; I am not explaining what actually is true in this story, what is truly the case in the movie, because our hero, the detective played by James Stewart, has been subjected to a confidence trick, a con, as has the viewer, and he, and we, wake up only twenty minutes before the end of the film. Like him, we have been deceived by appearances. But that’s not the point, not exactly. The point is that this story embodies a wish, and a dream, a powerful, all-consuming longing: What if a person you felt love for, and a responsibility for, died, and out of grief and guilt, you could somehow bring him, or her, or a replica, back to life? What if you could do that?

You would be, in effect, inside a dream.

There’s a giant coincidence at the center of this story that’s absolutely implausible and, upon consideration, impossibly contrived. I once asked Robert Pippin, a Hegelian philosopher who teaches at the University of Chicago, about this coincidence. Pippin has been absorbed and obsessed by this flm and has written a fne book about it. In answer to my question, Pippin said, well, Hitchcock loved surrealism and absurdity. He loved the films of Luis Buñuel. But for me that doesn’t explain why many viewers accept the outrageous contrivance of Vertigo’s plot.

Those who accept this plot probably do so because they, too, share a consuming and almost unconscious wish that it might be possible to bring someone you once loved back to life. This wish, this longing, is so obsessional that it sweeps all considerations of plausibility away. You’re hypnotized by it; you’re in a dream world. You’re spellbound inside a semirealistic fairy tale. A story that’s only a fantasy is not the truth—but a story that immerses you in a character’s fantasy and then makes you wake up from it, that may be the truth.

The film is beautifully shot; the soundtrack music, by Bernard Herrmann, is derived from Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde and is hypnosis music, with endlessly repeating sequence structures. Many viewers are simply overpowered by the entire show; skepticism dies under the force of that wish. As the novelist Joan Silber wrote to me in a letter about this, “The strength of a con isn’t its plausibility but how much people want to believe it. This is why people buy face cream that will make them look young forever.”

I first saw Vertigo in a theater in 1958 when I was eleven. I’d never seen anything like it. Later, in 1963 or so, it was broadcast on TV, and I saw it at home with my mother. My mother wasn’t buying any of it. Every so often, sitting over there on our reupholstered sofa, she would make a noise, “Pfffftttt,” the sound of disbelief, of enraged skepticism. Maybe she had a stake in the matter: her first husband, my father, had died at the age of forty-five of a heart attack when I was eighteen months old, and he never came back to life, and nobody, and certainly not my stepfather, was ever like him, and that was the truth, and all those lived-through consequences had been my mother’s life.

My mother, in her perpetual grief, didn’t believe that movie. There on the sofa, she gave a Bronx cheer to the beautiful wish: the whole story was just narrative bullshit for her. She had awakened from that particular dream a long time ago.

Bringing the dead back to life? Finding a replica for the person you lost? Pfffftttt. That was a wish and a longing for others, not for her. Such a longing is what Montaigne described as a soul error: desiring something that you know you can’t have. In this world, you can’t bring dead people back to life. A story that not only portrays a fantasy but also immerses the reader in it may be a con job, but fantasies, and the characters who are under their spell, are at the heart of much storytelling, especially among young people. Adolescents live in the iron grip of their fantasies. And some fantasies are nearly impossible to give up. Maybe we shouldn’t have them, but storytelling gives us license to indulge them. Many adolescents are spellbound; I certainly was. In my adult lifetime, I’ve probably seen Vertigo at least twenty times. When I read, sometimes I still am spellbound.

But let’s allow the film critic David Thomson to have the last word about Vertigo: “It’s a test case: If you are moved by this film, you are a creature of cinema. But if you are alarmed by its implausibility, its hysteria, its cruelty—well, there are novels.”

To which my answer is: Sorry, but no. Many classic novels do exactly what Vertigo does. Vertigo is, after all, adapted from a novel. We shouldn’t kid ourselves. The question is: How do we cast a spell in a story so that the reader ignores all the implausibilities we’ve put there? And under what conditions could we honorably do that? When powerful desires or fears overpower our common sense and we deploy all the technical resources we have—that’s when.

Worrying about the plausibility of dreams, I wrote a few months ago to my teacher in Buffalo in the 1970s, Irving Massey, a person of great wisdom, now in his old age. I asked him, “Irving, why do we always believe our dreams when we’re dreaming?” He wrote back: “Maybe dreams aren’t experienced as implausible because, as registers or transcriptions of what we feel, they aren’t.”

That’s beautiful.

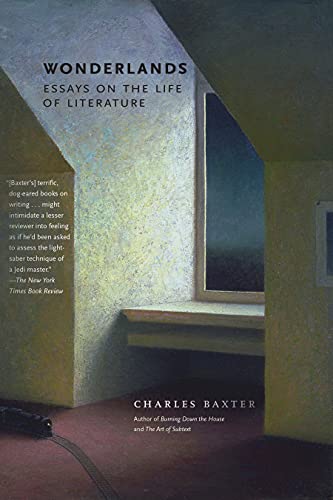

Excerpt from “The Unreality of Dreams” from Wonderlands: Essays on the Life of Literature. Copyright © 2022 by Charles Baxter. Reprinted with the permission of Graywolf Press.