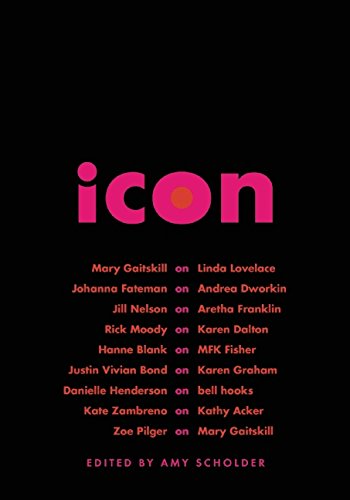

In the new essay collection Icon (edited Amy Scholder; published by the Feminist Press), writers discuss their relationships with public figures they’ve idolized, obsessed over, worried about, and been inspired by. Contributors include Mary Gaitskill (who pays homage to Linda Lovelace), Johanna Fateman (on Andrea Dworkin), and Kate Zambreno (on Kathy Acker), among others. The pieces vividly blend biography and autobiography, moving from tribute to confessional and back again. In the essay excerpted here, Justin Vivian Bond writes about Estee Lauder model Karen Graham’s serene and reassuring appearance. The “state of grace” it suggested helped Bond “escape into an image I could create of myself and for myself.”

Jungian philosophy is one in which you are supposed to be put in contact with your subconscious mind. Some people might call it your unconscious mind. In my case that is more apt. I’ve been very tapped into my unconscious mind for quite some time now. So much so that often times I don’t feel like I have to think at all.

The psychic told me that she saw a lot of “cat” energy around me, and she surmised that in a former life I might have been a guard at the temple of Dendur. I thought that sounded like something I might enjoy doing; in fact, even in this life I’d been raised in church. In any case, she said I seemed like the kind of person who would protect cats. That much is certain. I do love cats, and I’ve always had cats around me. My cat Pearl and I have a very close relationship and, come to think of it, I do have a lot in common with cats. You know how common it is see a cat staring at a wall? I’ve heard people say so often, “I wonder what that cat is thinking about.” Well I can tell you exactly what cats are thinking about. They are thinking about nothing. They are not thinking anything at all. And the reason I know that is because I do the same thing. I keep one entire wall of my bedroom completely blank so I can stare at it and not have to think about anything including what’s on it. Sometimes I don’t want to think, I just want to sit and look at a wall. It’s the way I am. In a strange way it makes me feel pretty. Is that bizarre? I read somewhere that models practice a blank middle-distance stare. That in order to look truly at ease you have to clear your mind and see nothing so the viewer can project anything they want onto you.

Which reminds me of how I spent a lot of my time as a kid. I would look at fashion magazines. My absolutely favorite model was the one for Estée Lauder. She was blank and sphinx-like, only more modern because she was wearing lots of makeup. I decided that with enough makeup on you could convince anybody of anything. So I stared at her for hours on end and convinced myself that one day I would be seen as the person I knew myself to be—but until then I had to hide her in order to survive. All I had to do was to wait, and believe, and keep staring straight ahead at the future. She, the vision of blank perfection in the Estée Lauder ads, assured me I would become the person I am today.

In high school I tore every advertisement I could find with her image on it out of magazines. I tore them out of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Town & Country. In the storage closet of the art classroom in my high school there were stacks and stacks of magazines. I went through every page of every one of them. I went to the local library and checked out magazines and ripped through them, trying to find this one particular model. By the time I graduated from high school I had a thick stack of Estée Lauder ads and mailers for Estée Lauder creams and scents from The Bon Ton, our local “high end” department store.

I had spent more time looking at her face than probably any face before or since. I drew her in pencil and pastel; I painted her in watercolor, acrylic, and oil. The first piece of art I ever had in a museum was a pastel drawing I did of the Estée Lauder model, which was included in a show of notable artworks from local high school students at The Washington County Museum of Fine Art in my hometown. The first painting I sold was a painting of her, a watercolor I sold to the local electric company, Potomac Edison. I won blue ribbons at the county fair—ribbons in both the youth and adult categories—for pictures I had done of her. I stared into her face and saw a gleaming smile with impenetrable, dead eyes. I’ve been trying to replicate that detached, dead-eyed smile for my entire life. Nothing is more appealing to me than a dead-eyed smile. It’s all I’ve ever aspired to, a kind of dispassionate engagement, which is calculated, informed, and unperturbed. Her dead-eyed smile says, “I’m smiling at you because I’m cognizant that this is appropriate behavior even if I feel nothing. What I’m doing I’m choosing to do with intention.”

My mother used to ask me all the time, “Why that woman?” “What is it about her?” “Why do you always have to look at that woman’s face?” And all I could come up with was, “Because she looks SERENE!” That’s all I wanted in my life, a little piece of mind, serenity, detachment—to escape into an image I could create of myself and for myself. I wanted to live in that state of grace.

Having grown up under the unflinching gaze of the gender police at home and in the streets, all I wanted was to escape—to be able to express myself as I was or as I wished to be. The Estée Lauder model was the quintessential aspirational white woman of elegance, pictured as she was in perfect eye makeup and perfect teeth, whether in a perfectly clinical setting, clean and unsoiled, or in an elegant home surrounded by Ming vases and Chippendale furnishings.

According to the Estée Lauder ads, this woman only read out of doors where she was pictured on the moors of Scotland holding a bouquet of heather in one hand and a book in the other, or when she stood starkly in a white dress against a privet, with a letter in her hand having carelessly dropped the envelope to the ground. What could that letter have said? Who could it have been from?

Maybe she never actually read at all; she wasn’t actually looking at either the book or the letter. She was staring blankly off into the middle distance. Maybe she was struggling with some kind of moral dilemma as to whether or not to follow her heart or her commitments to home, family, and tradition. So much to think about . . . and yet it seemed the only place she could find the space and time to read or think was when she was out of doors, away from her pottery wheel where she was pictured confidently at work on a bust of one of her children, or next to her bathtub where she was only photographed in a robe, high heels, and stockings. She certainly wasn’t allowed to let her mind wander when she was in the dermatologist’s office prepping for the latest Estée Lauder skin treatment with hairdryer tubes swinging around behind her, adding an aura of the ultra-modern cleanliness and whiteness. No, it was only on a park bench in a plaid skirt with a nosegay in one hand and a book in the other that she could attain any measure of intellectual freedom, but still the camera of Victor Skrebneski, relentless in its drive for perfection, remained focused on her and she on it.

At the time, I wanted so badly to get the hell out of my parents’ house and the stifling small-town mentality in which I was raised. I knew I could never be who I was meant to become there, that I would never be seen for whom I truly was until I was far, far away. So until I could make my move toward freedom I escaped into movies and magazines.

The astrologer reading my chart said, “Well, I guess I don’t need to tell you but you’ve got a very difficult chart!”

I said, “Oh, of course!” as if I knew this. I didn’t want her to think I had one of those unexamined lives, as if I didn’t know anything about myself. I nodded my agreement in a sly, casually knowing way, “Oh yes, of course, very difficult.”

She said, “You’ve got two grand crosses in your chart.” “Does that mean I was born double-crossed?” “Basically.”

I was born on a full moon with the sun in Taurus, the moon in Scorpio, and my rising sign in Cancer. I was also born with Mercury in retrograde. I’ve heard many people joke that between their period and PMS they only have about four good days a month. Well, I’ve only got about three good weeks every quarter because Mercury is only in retrograde three weeks out of every quarter of the year. That’s my time. I can’t help but think that while most people have all those other weeks to be happy and get themselves sorted out, I’ve got to get busy when Mercury is in retrograde, which makes my good days limited, but probably better than most.

So anyway, this psychic started telling me all these things about myself and I half-listened, focusing on how best to respond in order to get the most out of her, coaching myself with thoughts like, “Ask questions so you seem engaged . . . Try to be insightful about yourself . . . Quick, say something . . . Keep her talking . . .” I took a lot of notes and afterward I played the whole recording back. I was surprised by what I heard: She had asked me an awful lot of questions. Shouldn’t she have been more declarative? I didn’t need more questions. I wanted answers!

Once again I was left to my own devices. What else could I do? I boarded an airplane and began to stare off into the vast nothingness before me—but my joyous vacancy kept getting interrupted by the myriad questions the questionable psychic had peppered me with. I thought, “Oh Goddess! Here I go again, forced into bearing even more involuntary thoughts.” Sometimes I just don’t want to think! Finally I had to ignore the space in front of me and go inward. Terrifying!

On this particular day I was on a flight to California. I had already flipped through Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, reading a few articles on the stiflingly myopic lives of the rich and famous. After having compared myself favorably to their desperate foibles, I settled in for a bit of self-examination. One of the questions the psychic had asked me was, “What do you crave?” It took me a long time to come up with an answer to that one. After a couple of hours of thinking, meditating, and staring, the only two things I could come up with were oysters and beautiful surroundings. I’ve always enjoyed oysters because they seem glamorous and adult. When I was a child at Thanksgiving we had regular stuffing and stuffing with oysters in it. The oyster dressing was the dressing that the adults got to eat, so I couldn’t wait until I was old enough for that one. And every now and then my mother would fry oysters to make sandwiches, which I didn’t actually like, but which I did enjoy eating because they made me feel like a grown-up. It wasn’t until I got older that I discovered that you could eat oysters raw. Although it was disgusting at first, at a certain point it made me feel like I was infusing my spirit with the waters of Oshun. Eventually my love of the oyster became elevated to the spiritual.

I read the book Tipping the Velvet, about a working-class lesbian who dressed as a man and came from a family of oyster people. So I guess eating oysters also makes me feel a bit like a cross-dressed lesbian, which is something everyone should experience for themselves if they can. I’ve dated many cross-dressed lesbians. I was even married to one, but I’ve never actually felt like one myself until I’d read Tipping the Velvet and went on an oyster rampage. From that day on, I resolved to eat more oysters, which seemed completely doable.

But as for the beautiful surroundings, I started to think that that might be problematic. At the time, I was living in a loft on Second Avenue above a very disreputable hole-in-the-wall bar called Mars Bar. They played loud music, all of it wonderful, old-school, downtown New York punk. The place stank to high heaven, like the ghost of dead junkies who were left to rot in their own piss. My bedroom was directly above the bathroom, which I am quite sure acted as a shooting gallery for the few junkies and speed freaks who were left in New York City. Some people might have thought they were a pestilence—the junkies and speed freaks—but to me they were all we had left. However, they did not contribute to an aura of sweetness, and ultimately I was forced to duct-tape all the cracks in my walls and floors, and stuff quilts in holes to keep the stench from coming into my shabby, chic boudoir. It was sort of like living in Green Acres, only instead of a farm outside it was a crack den. It was interesting, it was fun, but I wouldn’t call it beautiful.

Sadly, my time in Crack Acres was coming to an end because the building was scheduled for demolition. All of its inhabitants as well as the cockroaches and cokeheads at Mars Bar were being forced to evacuate to make way for a new steel and glass condominium tower which was part of the Avalon development project going up between Second Avenue and Bowery. Avalon had already been responsible for the destruction of McGurk’s Suicide Hall on Bowery, where in the 1890s Bowery prostitutes would go to commit suicide. It is a storied block. I had heard tales of murders in my own hallway too gruesome to go into here. The building had been homesteaded by Ellen Stewart and other members of the La Mama family in the late 1970s. Across the hall from me lived John Vaccaro, one of the founders of the Ridiculous Theatrical Company, who had worked with Charles Ludlam and Jackie Curtis and a bevy of downtown legends in 1960s. In an odd way, John reminded me of my Pappy in that he was nasty, rude, and mean, but he had so much fun being that way you couldn’t help but get a kick out of him.

Fortunately, because I did get a kick out of him, he liked me and would come over and share stories about working with Jackie Curtis, who is a personal hero of mine, and show me pictures of my trancestors in their youthful glory, when their courage, outrageousness, and heavy drug usage paved the way for the life of relative acceptance that I am able to enjoy now.

The last party in my loft took place on gay pride weekend. The Monday afterward I put my things in storage and went on the road for six months. By the time I found myself on that airplane, post-psychic reading, the luxury of stability and beautiful surroundings was indeed something I craved.

Finally, in February of the following year, I moved into my current apartment on East Twelfth Street and began feathering my nest. What do you crave? Oysters and beautiful surroundings. After returning from California I ended the tour supporting my second record, Silver Wells, with a concert on Fire Island in the Cherry Grove Community Center. A gay couple I knew said, “You must come out to Sag Harbor sometime.” I’d never been to Sag Harbor, but I knew it was an enclave (I just love the word “enclave.” It makes me think of naked bohemians running around Laurel Canyon or tubercular artists living in Giverny; some sort of wild and privileged gated community where the rich and talented make all of their mistakes in private). I thought to myself, that sounds like beautiful surroundings so I said, yes I’d love to. I’d spent enough time around dirty queers; I’d spent enough time waking up in tents, surrounded by spilt lube bottles with amyl nitrate spills which had burned their way through tent floors, and seeped into the topsoil, leaving despoiled earth in its wake. I needed to up the ante and start hanging out with some nice-smelling bourgeois homosexuals. Don’t get me wrong; I love the dirty queers; they’re my people. But on occasion it’s nice to wake up on a firm mat- tress surrounded by expensive knicky-knacks. It was time for me to engage with a different class of people, to broaden my horizons, and step into a land of high thread-counts and designer wallpaper.

On the appointed day, I got on the Jitney to Sag Harbor where my friends have a beautiful home on one of the main streets downtown. After putting down my suitcase they gave me a tour of their home and gave me my pick of any of the guest rooms. The top floor was the attic, which had a rustic charm and beautiful wooden eaves. I noticed that on the bed there was an Hermès blanket and I thought, “This is where I shall sleep tonight!” Even though it was ninety-six degrees and there was no air conditioning in that attic, I resolved that since this might be my one chance to sleep under a Hermès blanket by God I was going to sleep under it! So I turned on the charming vintage Westinghouse fan, which sat atop a beautiful antique marble table next to a sculpture of a laughing cupid, crawled under the Hermès blanket, and slept better than I can remember having ever slept in my adult life. What had I been thinking all those years curled up with goat boys in tents on beds of moss in the wilderlands of Canada, Tennessee, and Northern California? Clearly, a Hermès blanket under the eaves in Sag Harbor was where I was meant to be!

In the morning I awoke, showered, and skipped down- stairs in my finest chinoiserie to a breakfast of lemon buttermilk pancakes, warm maple syrup, fresh coffee, and fruit compote. While I was enjoying my repast, my host said, “I don’t know if you’d be interested, but I farm oysters. Would you like to harvest some of my oysters with me this afternoon?” I sat bolt upright, shocked. At first I thought I was in some sort of twisted game, some sort of high-class bourgeois version of Punk’d. Was he kidding me? But I realized, no, everybody around here is sincere. I collected myself, reigning in my caustic cynicism, “Why yes, yes I would, I would like to go and farm oysters with you today.”

“Well, we can either go around noon or in the afternoon, say, around four. Which would you prefer?”

Now I don’t go into the direct sunlight. I don’t do it. I don’t enjoy it. I have listened to Noël Coward’s tunes, I know all about mad dogs and Englishmen, and even though I’m not a mad dog, nor am I English, I still refuse to go out in midday sun. So I said, “Let’s go later in the day. I think the four o’clock time would be perfect. Meanwhile, I am going downtown to do a little shopping.”

I set out in an all-cotton, breezy ensemble with a hat to keep the sun out of my eyes, feeling very white-woman-of-elegance and headed to downtown Sag Harbor. As I made my way around consignment and antique shops and stores with any and all kind of pickled and exotic canned goods, jams, sundries, I came across a stationery store. That’s just what I need! I went in thinking, I have got to find the perfect stationery to let people know who I am and what I stand for as an aspirational white woman of elegance. This is ground zero, a place for me to begin defining myself and my new role in life. I spent hours in there. I thought, Should I get stationery that has a “V” on it? Or should I get stationery that has a “B” on it? I think it would be more traditional to have my last name; “B” for Bond. But then I thought, No, use “V” for Vivian, to celebrate the declaration of my new identity as a transperson, “V” as my pronoun of choice. But then I thought, Maybe that’s too obvious, maybe I should have something more subtle, something more elegant or whimsical. It was so confusing.

I spent hours and hours until I finally settled on note cards with a ladybug and a leaf, since I’m a dendrophile, which is also the name of my first record. I left the store very proud of my new stationery. It wasn’t until I got home that I realized what I was really declaring was that I was a sentimental thirteen-year-old girl! Fortunately, I know enough goofy people I could send those cards to that it doesn’t really matter. I’m sure lots of people would be delighted to accept me as a sentimental thirteen-year-old girl. I’m lucky that way.

I made my way back to my friend’s house because it was getting to be time to harvest the oysters. I was trembling with excitement. We loaded up the station wagon and made our way down to the harbor where my friend kept a charming little red motorboat. As we were unloading the station wagon I noticed a pair of waders. I said, “Are we going to be wearing those?” He said, “It’s not necessary because in August the water is not that cold but if you would like to wear waders you certainly can.”

I said, “Yes I would like to wear waders. That sounds fantastic.” So we put the waders in the boat and made our way through the harbor past the yachts and all of the expensive people, places, and things. He took me to a place where there were rows of rope coming out from the shore, which were, as it turned out, his oyster beds. I excitedly slipped into the waders and put on my round l.a. Eyeworks sunglasses, the ones that make me feel like Joan Didion in the photo on the back cover of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, and stood there in the water going blank. I was frozen like a statue.

“Would you like to help?” he said.

Now ordinarily I’m not a helpful person. I don’t like being helpful. It’s a terrible thing to have to admit, but it’s true. I’ve heard many people at a dinner party or at a luncheon say, “Is there anything I can do to help?” So I say it, too, but I always silently pray they will say, “No thanks. Just sit and enjoy your cocktail.”

When I was in college I was hired by the costume department to do my work-study hours there, in spite of the fact that I did not know how to sew and that I knew nothing about costume construction. I didn’t even know how to do a load of wash. But what I did know was how to gossip. So they would give me some fake cherries, a hat, a needle and thread, whatever, and I would sit for hours and gossip while I made gestures toward the hat as if I was going to sew those cherries on it so that someone would end up with a fantastic period hat to wear in a production. I never did get the cherries attached, but I certainly made the time go by for the others.

But when my friend asked if I wanted to help harvest the oysters, I had a feeling of genuine enthusiasm such as I had never experienced before. “Yes! I would like to help!” I wanted to help very much, indeed. I wanted to learn how to harvest oysters because oysters were one of the two things I craved in this life. Yes please, let me help!

So I grabbed a pair of blue Playtex Living gloves and a great big brush and I sloshed my way over to where the beds of oysters were waiting to be harvested. The oysters were in these big, plastic containers attached to ropes on a pulley system and they were covered with algae and scum. It was my job to take the brush and scrape off the algae from the plastic containers that had holes in them so that the water could flow in and out, and the oysters would be in fresh water at all times as they grew and multiplied. I scraped the algae off with the fervor of a newly minted fishwife.

Before I knew it I was standing there in the water with my Didionesque sunglasses on, the Playtex Living gloves overflowing with oysters in their shells, in waders, with the sun behind me shining down on beautiful clapboard houses of Sag Harbor—and for the first time I felt like I was where I truly belonged.

All of the sudden I had a flash! I flashed to an image of myself staring at a particular photograph of the Estée Lauder model. It was an image from a magazine ad campaign in 2000, when this model came out of retirement to promote a moisturizer for middle-aged women. In the photo she was standing in water, in waders wearing a plaid shirt with a hat on and holding a fly-fishing rod. All of the sudden, it was as if she and I were one and the same person. She had been someone I had aspired to be, someone I had admired and dreamed about, and fantasized and projected all my hopes and dreams onto, and all of a sudden, in middle-age I was in the same position as she was, with the same posture wearing the same outfit.

I said to my friend frantically, “take a picture, take a picture, take a picture!” I threw him my phone and he took a picture, and it was as if, for the first time in my life, everything was as it should be. It was as if I had been reborn into the image of myself I had always secretly carried within my imagination, but had never quite been able to achieve.

You see, I didn’t know much about this Estée Lauder model, but I knew that she had been replaced in 1985 and I never saw an Estée Lauder ad I cared about again until 2000 when one day I was flipping through a magazine and there she was again—my model in a fly-fishing outfit. That was the last image I had seen of her. And here I was in almost the exact same outfit in Sag Harbor. For a moment, I wasn’t sure who I was. Was I my model? Or was I myself?

When I got back to the house in Sag Harbor, and after consuming twice my weight in oysters, I settled in under the eaves, beneath the Hermès blanket. Suddenly it occurred to me that it was no longer 1985 or 2000; we are living in the age of the Internet. I grabbed my iPad and Google-imaged the model whose name I had discovered years ago in a book of photographs by Skrebneski, a name that was pro- found in its unbridled WASPiness: Karen Graham. It was as if I had found a treasure trove filled with gold coins at the bottom of the ocean. Image after image of Karen Graham appeared before me, including the picture that had appeared seemingly out of the blue in 2000 when she was dressed as I had been dressed earlier that day. It was as if I were being reunited with a long-lost lover!

After exhausting myself looking at her still images, another miracle happened. I found a video! I’d never seen her in motion before, and the idea of seeing her in a video was almost too much for me to bear. And yet there she was in a video made by the English fashion photographer, Nick Knight. Evidently Knight had shot a video series called More Beautiful Women as an homage to Andy Warhol on the occasion of the millennial celebration of British Vogue and one of the models he videotaped was Karen Graham.

He asked each of the models to pose against a white backdrop for two minutes without telling them what it was for or giving them any instructions on what to do. Every model revealed herself in one way or another. Alek Wek, the Sudanese-born British model, stood perfectly still for two solid minutes. Carmen Dell’Orefice, the septuagenarian goddess, took that opportunity to make a PSA about breast cancer awareness and gave herself a breast examination. But Karen Graham simply stared and occasionally smiled or moved her head ever so slightly all the while looking very uncomfortable as if she were waiting for some instruction from the photographer or a reason to be there until one minute and eight seconds into it, when she utters rather vaguely, in a clear, feminine voice with a lilting southern drawl, “Two minutes is a long time . . .” Two minutes is a long time! At the end of the two minutes she said thank you, walked away, and has never modeled or been heard from again.

I needed to know more. I began researching Karen Graham and discovered some basic facts from Wikipedia. She was born in Gulfport, Mississippi in 1945. She studied French at Ole Miss, the bastion of education for the old-school southern gentility, and later attended the Sorbonne in Paris. After graduating, she moved to New York, where she hoped to become a French high school teacher. While looking for a position, she went shopping at Bonwit Teller, and on her way down the stairs bumped into Eileen Ford, who gave her a modeling contract. She went on to appear on the cover of Vogue over twenty times, putting her in second place for most Vogue covers of all time. By 1973, she signed to become Estée Lauder’s exclusive spokesmodel. She retired in 1985 at the age of forty while she was still on top. From then on she stayed out of public eye until making her one final brief appearance in 2000, when she appeared in Estée Lauder’s Resilience Lift face cream in an ad campaign aimed at “mature” women.

Her personal life remains very private except for a few details, which appeared as headlines. In 1974, she was engaged to be married to the British TV personality David Frost. But she left him at the altar when, according to Lee Israel in Estée Lauder: Beyond the Magic, Delbert Coleman, the owner of the Stardust Hotel in Las Vegas, flew to London with a great big diamond and persuaded her to marry him. Coleman was allegedly involved in many shady real estate deals on the Nevada strip. According to Beyond the Magic, by 1980 Karen Graham was paid half a million dollars a year for thirty-five days of work. These biographical facts make me think Karen Graham could have been the heroine of a Sidney Sheldon or Harold Robbins novel, with such titles as The Other Side of Midnight, A Stranger in the Mirror, Rage of Angels, The Naked Face, or Nothing Lasts Forever. But it wasn’t until after her retirement that I discovered that Karen Graham’s story took on a more interesting dimension. What did she do with her time?

She left the city and moved upstate to Rosendale, New York, where she opened a fly-fishing school—“Fly-fishing with Bert and Karen”—with a fisherman named Bert Darrow. She has been there since except for her brief return to modeling in 2000. It was at that time she gave her only in-depth interview to Dan Fallon of The Flyfishing Connection entitled “The Butterfly and the Trout.”

It was in this interview that Karen Graham finally began to reveal herself to me. I was floored. Karen Graham seemed to be describing my own childhood when she said, “I would spend almost every afternoon out in the woods near my house observing nature. I would build little homes for me out of moss, ferns, or straw. Many afternoons after school I would spend hours crouched on that old log peering into the green lagoon beneath me. I was fascinated with the tadpoles and slithering creatures. I was in trouble when I found out my uptown boyfriends’ idea of an outdoor adventure was sitting around a swimming pool balancing a silver reflector to speed up his tan.”

Uncanny! For all those years I’d been wondering, What is it about this woman? It was as if she were speaking for me. There was more to her than just the dead eyes and the smile.

In hindsight, it was as if she had been telegraphing to me that my dreams had value. Who I wanted to be and what I wanted to do with my life were possible, in spite of what anyone around me might say. And even today, as I continue to struggle with the conflicts inherent in being a social butterfly and performer versus my inner craving for rural solitude, I still feel compelled to express my gratitude by making myself available to the many strangers and friends who come to see me perform, that the “tadpoles and slithering creatures” who exist behind the facade remain and are of equal, if not greater, value to what their inspiration allows me to present. As Karen Graham once said, “I suppose one can’t help becoming rather addicted to the finer things in life. It didn’t take long after my first real modeling success in New York for me to understand the difference between hotdogs and caviar!”

Interestingly, Karen Graham became a supermodel at a time when a model’s name did not appear on the ad with her. For fifteen years she was the face of Estée Lauder. Estée Lauder herself was quite pleased for people to think that Karen Graham and she were one and same person. But Estée Lauder’s story was something else entirely. She was born Josephine Esther Mentzer in 1908 in Corona, Queens. Karen Graham was born thirty-eight years later in Gulfport, Mississippi. By the time Karen Graham modeled for her exclusively, Estée Lauder was in her mid-60s. Estée Lauder’s legendary ambition and hard work had placed her at the pinnacle of the cosmetics business. Her ceaseless drive had taken her into a circle of friends that included such luminaries as the Duchess of Windsor and Princess Grace, along with socialites on the international party circuit. Estée was saying to women all over the world, This could be you, too.

As a small-town transperson, I was sure that what I wanted was to escape into a world of glamour and elegance, taste and refinement. I scoured books by famed interior designer Billy Baldwin, who, I found out later, was a gay man from Baltimore, Maryland, not far from where I grew up. Amazing to think of me as a child gazing into these books filled with environments designed by a queen from Baltimore and advertisements for beauty creams created by a Jewish lady from Queens, planning my dream house, my dream career, and my dream life. I went for it with the mantra, “Keep it pretty, keep it shallow, keep it moving.” But as I grew older and my critical mind began to assess what really mattered, I found that my childhood dreams remained as shadows, which hover over me—part of my unconscious mind. I had seemingly moved on to a more worthwhile and enlightened existence yet all I really craved were oysters and beautiful surroundings.

Rediscovering Karen Graham took me back to a formative moment and gave me permission to put on my waders and step into a new dream: to redefine and rediscover my own path again.

Excerpted from Icon, published by the Feminist Press. Used by permission. Copyright 2014. All rights reserved.