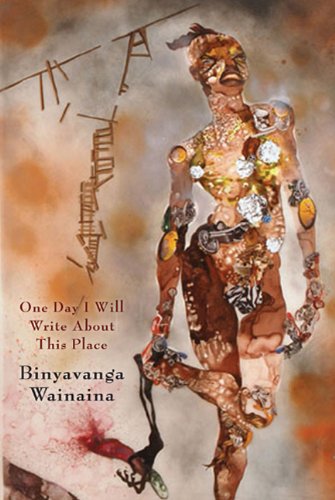

In 2005, Binyavanga Wainaina published a piece in Granta mocking the West’s need for African literature to present a uniform, tribal, black, desolate, and desperate homeland called Africa. He strives in his memoir, One Day I Will Write About This Place, to present life as it is and was, not in any fixed notion of “Africa,” but in the places he lived and traveled through: Kenya, South Africa, Lagos, Uganda, the Sudan. He does not present one mythical continent, but rather a fractured, complex, and ever-shifting collection of experiences. Sentence to sentence he jams ideas together, mimicking the way Michael Jackson, soccer, and school qualifying exams have influenced his world as much as corrupt politicians, ethnic killings, and famine. There are also many moments—moments that many readers will find familiar—that take place squarely in the mind of someone coming of age: “We drove to Nairobi today, my father and I, to the city. I have five pimples.”

At a young age Wainaina started reading two or three books a day, gobbling “them like candy.” He reads because books are an escape to other worlds, new places. And the words within these books grounded him in what he perceives as a floating and strange world; they are “concrete things.” Later, he writes to make sense of this world, to control that act of transporting. His emphasis on his surroundings makes it impossible to forget that he is bringing you to Africa, but to assume that that is the only point misses the point. While he may be saying, I cannot take you to “Africa,” he is also saying, I will take you to this place, to my Africa. In his home, with his family, in his mind. Here it is not just the African landscape that is beautiful, but also “The nightclub’s lights [that] are caterwauling above me, like a frenzied child with crayon lights, scrawling and scribbling with delight.” His point is that the Africa he sees—which is made of up thousands of differentiated sections, countries, neighborhoods—is his. He’ll take you there, but there’s never any doubt that the reader is being welcomed into the author’s particular response to a series of places.

Wainaina writes matter-of-factly about schooling, sibling rivalry, and politics, but he tempers them with re-creations of his obsessive, hypersensitive perception of the world. Against the flatter language, these moments of perception become airy and playful. They serve not only to dramatize a deeply internal experience but also to illustrate how his perspective often created a barrier between him and his peers—especially during his early life in Kenya.

One of the most beautiful sections is dedicated to a description of the neighborhood he visits in Nairobi after worrying about his five pimples:

Take the sun—give it ten thousand corrugated iron roofs—ask it just for the sake of asking, to give the roofs all it can give the roofs and the roofs start to blur; they snap and crackle in agitation.

Corrugated iron roofs are cantankerous creatures: they groan and squeak the whole day as they are lacerated by sunlight, their bodies swollen with heat and light, they threaten to shatter into shards of metal light. They fail, held back by the crucifixion of nails.

I want to heed Wainaina’s Granta article, so I worry about highlighting a section of the book that seems too stereotypically African, a scene that talks of the sun, the heat, the poor quality of housing. (Later in the scene there’s a violent fistfight.) But I also think that ignoring these sections would be equally missing the point, since it is not Wainaina’s intent to ignore or belittle those parts of Africa that resemble what Westerners associate with the mythical continent. Rather, he looks to contextualize these parts—to give them texture and distinct personalities.

Although exposing Africa’s diversity to the West is certainly honorable, what gives this memoir its pulse is how Wainaina creates a new sense of place for the reader. He captures the feeling of being somewhere, and this includes (perhaps most importantly) being in one’s own mind. Wainaina worries that no matter where poeple are crammed together, we are separated by our individual thoughts. He writes, “There are things men are supposed to know, and I do not want to know those things, but I want to belong.” But for all his emphasis on the distance between people, his book allows us to slide into his thoughts, to know what he knows, and to lose, or at least lessen, this feeling of separateness. This book is so powerfully written that while we’re reading it, we can almost belong to the same place.

Jena Salon is the books editor at The Literary Review.