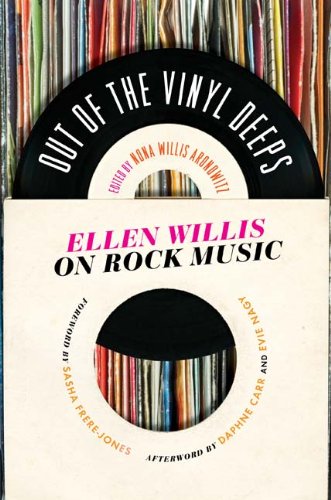

Ellen Willis is credited with two firsts. She was the first great female rock critic and the first pop critic for the New Yorker (from 1968 to 1975), breaking the gender ceiling in a male-dominated field and the class ceiling by writing about low-culture in a high-middlebrow context. Willis’s music writing is compiled for the first time in Out of the Vinyl Deeps (edited by her daughter, Nona Willis Aronowitz, with a foreword from current New Yorker critic Sasha Frere-Jones). It’s guaranteed to stay at the top of the rock-critic canon. Writing in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Willis was expanding the possibilities of a new form before it’d really taken any form at all.

Like the much-praised famous men of rock criticism’s ’70s glory days—particularly the holy trinity of Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, and Lester Bangs—Willis displayed a worldly engagement a lot of rock criticism (and rock music) doesn’t feel the need to reach for these days. For Willis, that engagement came as a necessity: Writing for the New Yorker, a publication that was skeptical about rock music, she took on the role of explainer more than a Cream or Village Voice writer needed to, writing stuff like this in 1968: “Among the many interesting developments in pop music has been the emergence of the LP record as the basic aesthetic and economic unit of serious white rock.”

Still, she did her explaining from the inside. Willis chose to approach rock on its own terms, as a pop thrill that opens up personal, social, and political possibilities, bringing in her own perspective as a Queens teen who’d grown intellectually and culturally in step with the music. “It’s my theory that rock happens between fans and stars—rather than listeners and musicians,” she wrote in 1969. “That you have to be a screaming teenager at heart to know what’s going on.” This remains a liberating insight: Start with your response and build from there. Her seminal essay on the seminal record Velvet Underground (taken from the 1978 anthology Stranded) begins, “I’ll let you into my dream.”

By exploring music’s ’60s growth and ’70s fragmentation in a clear, direct style, full of wit and great one-liners, Willis’s writing offers a boots-on-the-ground perspective that was self-interrogating while only occasionally overly indulgent, reportorial without ever feeling detached. Take this line, from 1972: “Bowie doesn’t seem real. Real to me, that is—which in rock and roll is the only fantasy that matters.” With off-handed elegance, that quote says a lot—about the relation between performer and fan, about the relationship a fan often has with her own conflicted responses to a new Important Artist, and about the reasons we’re drawn to rock in the first place. Mostly, though, it’s about privilege. Whose self-creation matters more here, Willis’s or Bowie’s? Who’s working for whom?

The balance between critical and personal is full of contradictions, and Willis loved exploring them (though one section of the book is called “‘the ’60s child,” she uses the funny ’60s term “cultural revolution” always with just the right mix of sympathy and irony). The best pieces in the book find her engaging the careers of artists that also thrived on social, sexual, and cultural tensions. Vinyl Deeps opens with a rock-criticism classic, her 1967 overview of Bob Dylan’s career originally published in Commentary (it’s miscredited to the short-lived rock mag Cheetah), which still reads like a perfect primer on his early years (“many people hate Dylan because they hate being fooled,” she wrote). In a sense, each of her favorite artists embody a key fixation for her: Dylan (the cat-and-mouse ironies of pop-celebrity genius), Beatles (community), Janis Joplin (feminism), Velvet Underground (bohemia), Stones (sexual persona), Who (spirituality), CCR (populism, popularity).

She loved these bands enough to make high demands of them; many pieces transition between euphoria and resistance, because skepticism (of hype, of empty product, of hand-me-down postures) is an essential pop response too. She didn’t give three-and-a-half star reviews, and since there were only about eight bands back then it allowed her to really dig and go toe to toe with the Gods. The Dylan pieces, which run through the mid-’70s and then pick up one last time with a Salon review of 2001’s Love & Theft, could be their own excellent little pocket-sized book.

Fittingly, Out of the Vinyl Deeps turns on a negation, Willis’s reaction to the Sex Pistols; punk’s anti-humanity posture (embodied by the Pistol’s anti-body “Bodies”) offended her humanism, and she had the guts to admit it, even as she acknowledged the undeniable force of the Pistols’ music. (The Clash suited her a little better; in the austere, jaundiced ’70s they were “post-crank…the first ’80s band.”)

By the late ’70s, sensing a de-politicization of rock, she pretty much abandoned music criticism for political writing. It’s too bad. In a sense, a lot of punk and new wave seemed to be taking a Willisian mix of thrill and resistance into the pop funhouse. But for her, taking on the Reagan Revolution seemed more urgent than sussing out the feminism of the Go-Gos or the class politics of the Replacements, and that’s totally understandable (though she could’ve written a great Beauty and the Beat review). Today, Willis (who died of cancer in 2006) is a legend of feminist cultural criticism and arts journalism in general. There’s a sense among some of her fans that she was a great cultural and political critic who got her start writing about rock. This collection proves the reverse might be true: She was a brilliant rock critic who left the game before she’d given all she could.

Jon Dolan is a freelance writer living in Brooklyn.