For a number of years in the late 2000s and early 2010s, Dave Hickey’s byline in magazines said that he was working on a book called Pagan America. There’s even a ghostly record of the title on Google Books, with a precise page count and ISBN, as though the manuscript were finished, paginated, and catalogued, but then withdrawn and locked away in the writer’s desk, left to be published, if ever, posthumously.

For those of us who were Hickey fans during those years of uncertainty, it was a shimmering promise. After the cold brilliance of his first book, The Invisible Dragon, and the warm love song of his next, Air Guitar, he was going to bring it all together into one grand synthesis, a story of America that would elevate us and explain us to ourselves.

It never materialized. As Hickey had written of himself, many years before, he wasn’t a big book kind of guy. He didn’t have the endurance to finish. He also no longer quite wanted to finish. When he had first promised the book to his publisher, in the early years of the new century, it was in the form of an argument. By 2015, when the mention of Pagan America quietly disappeared from his byline, he no longer believed it.

The argument was this: America at its most distinctive wasn’t Judeo-Christian or capitalist or even democratic in a simple way. It was pagan. Not an earth spirit paganism of the moors and glens, but a polytheistic, commercial, cosmopolitan paganism of the bazaar and the agora. We invested objects, people, and performances with the power of our dreams and fears, and then we organized ourselves around those idols in “non-exclusive communities of desire,” arguing about them, buying and selling pieces and images of them on the open market, trying to woo others into our camp and score points over rival camps. We were a democratic people, but to see American democracy clearly was to understand that our democracy renewed itself on a substratum of pagan devotions to movie stars, rock stars, oil paintings, charismatic political figures, football teams, ingenues, mystery novels, muscle cars, runway shows, action movies, and action painters.

The devotional icons for Hickey, the furniture of his blue eden, were people and things like Siegfried and Roy in Vegas, Waylon Jennings in Nashville, Chet Baker by the beach, Perry Mason on the UHF dial, Richard Pryor on the Sunset Strip, Leo Castelli on the Upper West Side, Bridget Riley in undulating waves of color or black and white, Gustave Flaubert on the page, Robert Mitchum on the screen, Robert Mapplethorpe’s photos on a coke dealer’s coffee table on Hudson Street, Susan Sontag holding court at the St. Regis Hotel, and Dr. J rising up and under and around to complete the greatest lay-up in basketball history. These were his personal fetish objects, but more important to understand was that we were all free to design and furnish our own edens and free to say thanks but no thanks to those representatives of government and official culture who would tell us what to consume for our own good, as though art were broccoli rather than gnocchi.

It wasn’t necessarily the best of all possible worlds, this anxious huddling around idols, pouring into and drawing from them energy, hoping to stay warm in the cold. Given our specific inheritance, however, it was for Hickey the best we had been able to do so far and preferable to the alternatives. It held us together, when so much else didn’t, because it educated us in how to passionately hold distinctive values without desiring to purge conflicting ones. It both sublimated and civilized politics.

Unfortunately, for Hickey and us, he was wrong that “ethical, cosmopolitan paganism” was ascendant. Across the board it is in retreat, not just from ethno-nationalists who would bend culture to the needs of the state and the Volk but also from puritanical intellectuals and activists who would regulate culture in the name of justice, equity, and identity. The other guys are winning. The pagans are losing. Hickey was not wrong, however, that cosmopolitan lives of the sort he described are worth cultivating and that a society in which such currents ran strong would be glorious, or at least rather fabulous. One can imagine a parallel universe version of the book that puts forth Pagan America not as an argument but as a vision of what we could be.

We didn’t get that book, but it is just such a vision of who we could be, which is simply more of who we are at our most interesting and dynamic, that animates Hickey’s best writing. He is an essayist not just of the jam session and the atelier, but also of the circles of community and conversation that emanate from those sites of primary artistic creation, of the painter and the critic, the novelist and the reader, the pop star and the fan, and the big-wave surfer and the Idahoan teen who knows that his Sex Wax T-shirt says something urgent about who he is. Hickey is a cartographer as well of many of the psychological and sociological traps and cul-de-sacs that can get in the way of creating or participating in such communities and conversations. And he is a grantor of permission and forgiveness, a purveyor of caring, knowing acceptance, and encouragement.

This last bit is perhaps the least remarked upon but most intensely felt of Hickey’s effects as a writer. As readers, we know when we are being judged, and for all the pungency of his opinions, Hickey isn’t judging. He is three-fourths a disaster himself, and he knows better than most that we are all struggling, self-sabotaging creatures. Embedded in his work is a conviction that the joyful and passionate instantiations of ourselves that sometimes emerge in the presence of art and culture are too precious to casually or presumptively reject. One could even say there is a Christian quality in Hickey’s writing, though it’s a Christianity of the early years, before Jesus signed with a major label, when the faith was a haven from the sternness of the Pharisees rather than an inheritor of their paternalistic moralism. His is a sinners’ church.

In a late essay, Hickey reflects on the decades of his life spent among the “casually damned . . . [the] rock and rollers, artists, poets, strippers, and hookers.” Living, partying, and playing with those who had been cast out, abandoned, or ignored by respectable society, he found a sense of camaraderie and a blessed lack of judgment. Part of the urgency of Hickey’s writing comes from a perception that even these realms of the damned are being colonized by the virtue-promoting institutions from which they had long provided refuge. So he writes to protect the places where he had found refuge from the people from and in whom he perceives judgment.

He has failed in the larger endeavor. The colonization continues. In the process of failing as a political actor, however, he has generated as an artist a new payload of freedom and solace for others, and he has extended his offer of citizenship outward even to those of us who are not the casually damned, to the pirates and to the farmers. In the land of Hickey, all are welcome, all are forgiven, and your eden is yours to furnish, as long as you extend the same generosity to your neighbor.

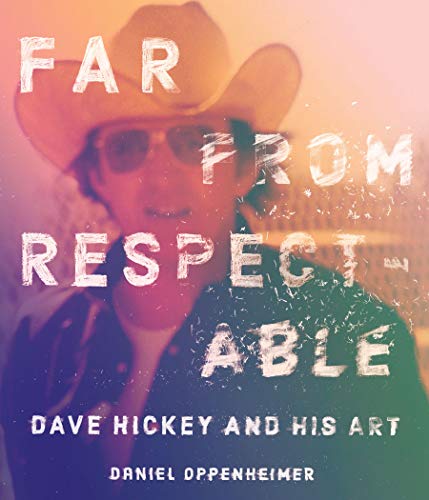

Adapted from Far from Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art, by Daniel Oppenheimer. Used with permission from the University of Texas Press, © 2021.