South and west of central Chicago, there is no 22nd Street. Rather, between 21st and 23rd, the signs read Cermak Road. This thoroughfare follows the Red Line down from the big-money Loop to the threadbare African-American South Side. Roughly halfway between those two poles it crosses Pilsen. The neighborhood’s name derives from the Czech—the people of Chicago author Stuart Dybek—and it has always been an immigrant enclave. In the twenty-first century, the neighborhood is also home to a large community of Hispanics. Thus, the moving, energetic Painted Cities—the debut story collection of a Chicago author to be reckoned with—describes the Pilsen of Alonzo and Flaca and Mrs. Calderòn. These folks prefer the name 22nd Street. They like the security of a number; their lives feel unmoored enough as it is.

Unmoored, and forever straying into violence. The opening story, “Daydreams,” ends in a gang shoot-out at a quintería, and the one of those killed may be the narrator’s older sister. At the end of his few pages of reflection, her murder remains an implication, only; it’s the chill given off by a single detail: “In the basement of our old house, my sister’s pink gown hung in a plastic sheath throughout my childhood.” Yet the bloodletting’s everywhere. In the second story, when the narrator reflects on his childhood pipe dream of panning for gold in the local gutters, he perceives the desperation behind it:

May Street [an easy walk from Cermak] was a place where I saw drunken men brawling to the death, I saw wives get beat by husbands, I saw children get hit by cars and then watched those… drivers get beat to bloody pulps.

Life on America’s urban margins, in other words, is nasty, brutish, and short. For fiction this verity remains evergreen, and Chicago has often enough been the setting. Dybek, in his generous blurb for Painted Cities, cites James T. Farrell and Nelson Algren, earlier chroniclers of how the City of Big Shoulders smothers its small fry.

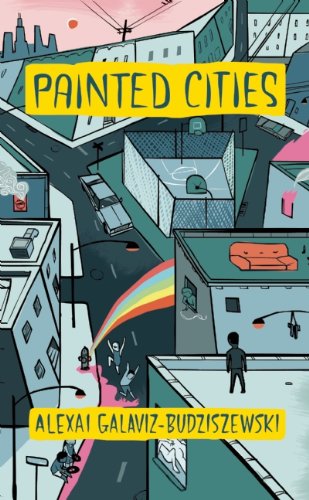

Happily, this author’s name combines two cultures: Galaviz-Budziszewski. He upsets expectation, his hardships at once bruising and yet life-giving. Consider the description of a graffiti artist’s greatest work, in the title story: “Within the basket of each tear a city appears, like a hanging garden, … the neighborhood … held within glass bulbs like holiday paperweights filled with liquid, begging to be flipped.”

Exactly, and in a number of cases here, the drama’s in the flip. The impact, that is, depends on some pirouette at the last minute, just as the opening “Daydreams” withholds the news of the shoot-out till the closing lines. In one case a boy will perceive an irresolvable family dysfunction, in another, an irrepressible saving love.

One or two of the epiphanies might be criticized as a gimmick, a memory hidden like a trump card. A reader might wish that at least one of the characters looking back were a woman (though the mothers, sisters, and girlfriends never lack for wholeness and spine), and might also become impatient with some of the moseying around. Still, I can’t cavil. Even the collection’s one outlier—the penultimate “Supernatural,” unique in both its use of the collective first person and its lack of retrospection—asserts the strengths that carry Painted Cities. As the title suggests, “Supernatural” brings magic to the mean streets. On summer nights, a “fluorescent haze” rises over the disused and polluted canal at the neighborhood’s eastern border, and this light show has wondrous effects. It’s rumored to heal the sick, but the true amelioration proves more subtle: “Those… holding babies, would be caught looking like their children, sharing their defenselessness.” Even the “gangsters” start “smiling like bashful teenagers,” and the mention of this softness immediately follows another tough insight: “Gangster faces change like masks. They’re defense mechanisms.”

The no-nonsense and the open-hearted, the social worker and the magical realist, strike their most spectacular balance in the centerpiece, the longest story, “God’s Country.” Again we have a man looking back, retracing a teenage ghetto odyssey. Again there’s violence: “twice a year Capone was beaten.” Yet the primary action concerns a friend who seems capable of bringing dead animals back to life. At the climax—just off “22nd Street”—he may even revive an overdosed gangbanger. A fiction of what’s worst about the inner city, that is, startles us with the stubborn promise of the place, as its recording angle detects the humanity in the least detail: “By high school … Chuey had adopted at least part of the Pilsen uniform: black Converse All-Stars. He still wore straight-leg jeans. The rest of us wore Bogarts—baggy pants with sixteen pleats cascading from the waist, tight cuffs.”

John Domini’s latest novel is A Tomb on the Periphery; he has a selection of criticism, The Sea-God’s Herb, due in May, and both a story sequence and a novel to follow.