BORN IN 1902, Pierre Verger became a successful photojournalist in his native France, in 1934 cofounding an agency whose members included the likes of Robert Capa and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He lived mainly in Brazil from 1946 until his death fifty years later, and in his adopted country devoted himself to ethnography, writing many books. But he was not a disinterested observer; fascinated by the persistence of Yoruba culture in the New World, he was initiated into the Candomblé religion, and after studying in Benin, he became a Babalaô or high priest of the Ifá oracle, and was accorded the new name Fatumbi, “the one who was reborn for Ifá.” In North America, however, as Alex Baradel (the curator of the Fundação Pierre Verger in Salvador, Brazil) writes—and despite the time he spent here, documented in the present volume—Verger “remains a mystery.”

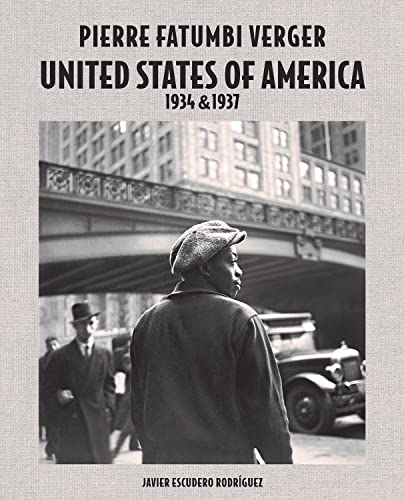

True enough: I had not heard of Verger until this book fell into my hands. It stems from two journeys, one made in 1934 on behalf of the French magazine Paris-Soir at the side of a pair of journalists, traveling mostly by train, sometimes by car; in 1937 he returned following a visit to Mexico, traveling by bus to New York. But this is not the kind of American road-trip documentary we have become used to seeing since Robert Frank unleashed The Americans in 1958. This is a slower-moving world with the stolid style suited to the Depression; Verger depicts it with an appropriately boxy sense of composition. He rarely goes for a close-up, preferring views that frame his subjects in a wider architectural or environmental context. This use of scale can also allow for Verger’s wit to assert itself; for instance, the distance necessary to encompass the whole of the Washington Monument turns the line of parked cars at its foot into a parade of ants. In his thorough, rather academic text, Javier Escudero Rodríguez emphasizes Verger’s intense empathy for the Black people he photographs—he explored Harlem with a depth and nuance unrivaled by other white photographers of the era—and it’s true that he generally comes closer to his African American subjects than to whites, wanting not just to see them and situate them but also to know them. Mostly unpublished during Verger’s lifetime, these images fill some gaps in the visual record left by American photographers (Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, et al.) in a period when that art flourished in this country. And it begins to introduce us to a fascinating and unexpected figure of consequence for what would later be called the Black Atlantic.