Before she published My Brilliant Friend, the first volume of her much-celebrated Neapolitan series, in 2011, Elena Ferrante was known for three short, violent novels about women on the outer boundary of sanity. Although their stories are unrelated, the books form a thematic trilogy. Each is narrated by a woman who embodies a different aspect of female experience—in Troubling Love, a daughter; in Days of Abandonment, a wife; in The Lost Daughter, a mother—and each is concerned with how these domestic roles constrict the lives of their protagonists. Ferrante is often asked about the classical influences in her work, and reading these books you can see why. They are strikingly compressed and spare, set largely in enclosed, almost anonymous, spaces that evoke the stage of a Greek drama, their focus turned inward on the narrator’s slow uncovering of the unconscious forces underneath ordinary family life.

The best-known of the three, Days of Abandonment, is narrated by a kind of contemporary Medea, a woman whose husband has just left her for the teenage daughter of a family friend. In an ominous early scene, she accidently breaks a bottle of wine while preparing a meal, leaving shards of broken glass in her husband’s food and making her wonder whether she secretly wants him dead. Later, after she sprays the house with insecticide, her son and the family dog mysteriously sicken. Paralyzed by the suspicion that she poisoned them in half-acknowledged revenge against her husband, she descends into temporary insanity, unable to care for her children or even open the door of her apartment. Eventually, there’s catharsis: She unlocks the door and passes through madness into relief and a species of resolution. But the strongest impression the book leaves is of the claustrophobia and horror of its earlier scenes, where it’s never really clear if she’s about to kill her husband, her children, or herself.

Ferrante’s next books, the Neapolitan series, move in a new direction. The protagonists of Days of Abandonment and Troubling Love were daughters, mothers, and wives. Their problems were domestic, their lives were private, their struggles confined mostly to their own minds. In the Neapolitan novels, Ferrante trains her vision, for the first time, on a female experience outside the family: the friendship of two women, Lila and Elena, childhood companions who still occupy each other’s thoughts decades later.

A shift in tone accompanies the shift in subject. Although the series is marked, like all Ferrante’s writing, by violent emotion and violent language, the classical form it most resembles is not the Greek tragedy but the epic. Ferrante’s first books took place largely in enclosed, almost anonymous domestic spaces; the Neapolitan novels are set against the backdrop of postwar Italy and move back and forth over events of almost half a century. Each installment begins with an index listing a large cast of minor characters, whose clashing interests and tangled feuds play out over the course of the story. Moving away from the inward-looking monologues of Ferrante’s first novels, the books are narrated in a headlong, almost breathless voice that leans heavily on parataxis and sounds spoken rather than written.

This is the epic’s traditional style, the action cam of rhetorical modes, and we are meant to understand that there is something epic about Lila and Elena’s friendship. From their first confrontation, when Lila drops Elena’s doll through a basement window, it’s clear that the girls are allies but also rivals. As children, they subject themselves to tests of courage that range from pricking themselves with rusty safety pins to thrusting their arms into an uncovered manhole. Growing older, they broaden their field of battle to include money, sex, and social power. The two are always measuring themselves against each other, always falling behind or surging ahead. Ferrante celebrates their constant sparring in the kind of effusive terms rarely used outside movies about team sports. Her play-by-play recaps of scholastic competition, in particular, are one of the small things that remind us we’re reading these books in translation; it’s hard to imagine a comparable work of American fiction listing, for example, all its protagonist’s grades and test scores.

The books are narrated by the adult Elena, a successful writer who has made a comfortable life for herself outside the poor Neapolitan neighborhood of her childhood. Looking back, she endows her and her friend’s younger selves with the archetypal qualities of classical heroes. In her memories, Lila, the daughter of an illiterate shoemaker, is something like Achilles: a “terrible, dazzling girl” who outshines everyone else without visible effort, the winner of every contest, the bravest, the fastest, the most skilled. (She is also thin-skinned, obstinate, and prone to “a rage that had no end.”) Elena is a different type of hero, dutiful and restrained, capable but hesitant. The daughter of a porter at city hall, she seems destined, by background and temperament, to succeed academically—to sit the civil-service exam or perhaps even to become a teacher. Goaded by Lila, however, Elena surpasses these expectations, pushing herself along the series of steps—to a local middle school, to a classical high school in the city center, to university in the north of Italy—that eventually lead to her successful career.

The most influential reading of the Neapolitan novels sees them as a version of the traditional bildungsroman, the story of Elena’s education and development. To become a writer, she has had to wrestle with her material and bring it under her control; to become an adult, she has to separate herself from her family and home. According this view, the main arc of the novels is Elena’s struggle to wrench herself free from the feminine “drama of attachment and detachment” of her friendship, as James Wood put it in his review of My Brilliant Friend.

This line of thinking links Ferrante’s novels to an established narrative of female friendship seen in coming-of-age novels like Lorrie Moore’s Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? and films like Nicole Holofcener’s Walking and Talking. In this story, an extremely close childhood or adolescent friendship is disturbed by the onset of adult life, usually in the form of one friend’s involvement with a man. These works are essentially nostalgic; the all-consuming friendships they celebrate are always in the past, part of a lost girlhood that can never be recovered. In effect, they reprise the traditional marriage plot: Friendship between women is a form of preparation for marital intimacy, at least from the perspective of the friend who’s left behind. Adult friendship, in this picture, can only be something lesser: less rivalrous, less envy-inducing, but also less important, less galvanizing, with less at stake.

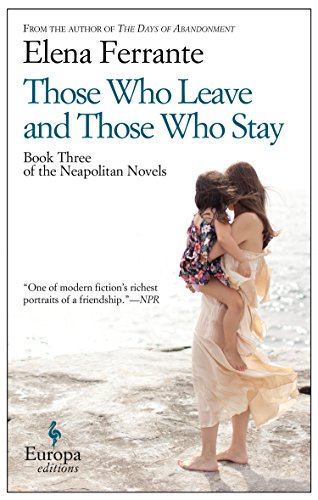

It is striking, then, how little the later installments of Ferrante’s series, which follow Elena and Lila as they move into adulthood, conform to this model of friendship. Both women marry, leave home, find jobs, and have children, but none of these changes manage to dislodge their competitive rivalry from its decisive role in their lives. At the end of My Brilliant Friend, the teenage Lila makes a strategic marriage to the neighborhood grocer’s son, whose money she used to produce a line of shoes after her own design. In the second book, The Story of a New Name, Elena remains a struggling student as Lila becomes one of the most powerful women in the neighborhood. In the third and most recent of the Neapolitan novels, Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, which starts when the two are twenty-four, the pendulum of their friendship has swung back around. Elena is in a position that echoes Lila’s at sixteen: She too is about to make a strategic marriage, to a member of Italy’s left-leaning upper-class intelligentsia whose social connections she exploits to publish her first novel. She feels “universally admired, haloed by a high level of culture.” Lila, meanwhile, has lost much of her former glory following a disastrous affair. When Elena, a newly published author, visits Naples at the end of the second novel, she finds her friend divorced, living in a slum, and working in a salami factory on the margins of the city. (Ferrante isn’t always subtle.)

Up to this point in the series, Lila’s experiences, more exciting and dangerous than Elena’s academic career, have taken up most of the story’s oxygen. By the same token, it’s the first book that’s really about Elena. It’s also the first book in which the extent of Lila’s influence on her friend is clear. The novel is divided into two main threads, political and domestic. It begins in early 1968, a few months before the May student demonstrations in Paris. The controversy over Elena’s first book, which some praise for being antiauthoritarian and others criticize for the same reason, leads Elena, for the first time, to take a position in an ongoing political conflict. She is sympathetic to the revolutionary goals of the student protestors, yet her experiences parallel those of many women in the left-wing movements of the time. The demonstrations she attends are chaotic and undisciplined, and no one but men seem to be able to talk. During long political discussions, she sits silently with the other women, feeling as if they are all “drowsy heifers waiting for the two bulls to complete the testing of their powers.” Only when she reads the work of the radical Italian feminists, whose violent upending of intellectual hierarchies reminds her of Lila, does her paralysis start to abate.

At the same time, Elena is facing the challenges of married life. After a modest ceremony, she and her husband move to Florence, where he assumes a prestigious academic position and she sets up house and wonders what to write next. Her husband, it emerges, is an overbearing pedant who doesn’t want her to go on the pill for complicated philosophical reasons. Instead of beginning another book, she has a child, and then another.

The two sides of Elena’s life converge in the novel’s final pages, as she and an old classmate fall violently in love and leave their families. Ferrante doesn’t present this as a particularly triumphant moment for Elena. There are ugly phone calls, fights, screaming recriminations. When Elena’s husband finds out, he throws the glass top of their coffee table against the wall; her daughters cling to her legs and beg her not to go. She tells them she’s not going anywhere, then slips out with her suitcase. Ferrante emphasizes that Elena’s motives are mixed: Here is at once the understandable desire to extricate herself from a bad marriage, the revolutionary impulse to put the theory she’s been reading in her feminist group into practice, and the secret enjoyment of making an undeniably bad decision for perhaps the first time in her life. Chief among her reasons, though, seems to be the desire to grasp yet another facet of Lila’s experience. Significantly, Elena’s new boyfriend is the same man who ran away with, and then abandoned, Lila years earlier. He has a reputation as a seducer, but the most effective weapon in his arsenal, one suspects, are his assurances that he was wrong to pick Lila originally, that Elena had always been the more brilliant of the two.

Elena’s willingness to turn her life upside down to score a dubious point against her friend seems like a mistake, and perhaps it is. Near the end of the book, Lila herself, now a successful computer engineer, listens in horrified silence to Elena’s plan. It’s hard not to share her frustration—all this, and we’re back where we started? But if there’s something frustrating about Elena’s need to repeat even her friend’s mistakes, something exhausting about how completely Ferrante inhabits her characters’ interminable struggle, the repetition only mirrors the fluid, constantly shifting experience of friendship itself. It is no accident that Ferrante has chosen this relationship—one tethered neither to the fixed roles of the family nor the dutiful solidarity of political sisterhood—as the model for her picture of women’s equality.

Namara Smith is an associate editor at n+1.