When Elizabeth Bishop took on the job of New Yorker poetry critic in 1970, she wrote to her doctor Anny Baumann, “Writing any kind of prose, except an occasional story, seems to be almost impossible to me—I get stuck, am afraid of making generalizations that aren’t true, feel I don’t know enough, etc., etc.” She failed to file a single review for three years, at which point The New Yorker decided to act as if the appointment had never occurred, so they could keep a good relationship with Bishop, who had been publishing poetry with the magazine for thirty years.

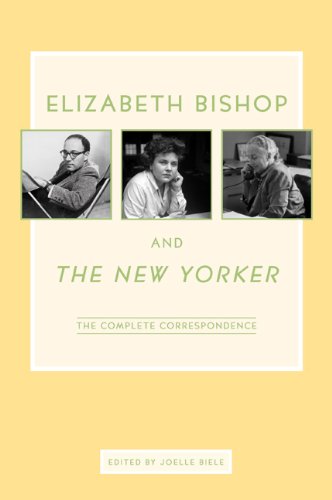

Today marks the one-hundredth anniversary of Bishop’s birth (she died in 1979), and this month three new books offer reviewers plenty of chances to grapple with the trouble of generalizing on her work. Bishop’s complete Poems and Prose (also available as a two volume set), and The New Yorker: The Complete Correspondence, come on the heels of the complete correspondence between Bishop and the poet Robert Lowell, which was published in 2008.

These volumes give a sense of the arduous work behind the clear, easy movement of Bishop’s prose. Bishop, a Pulitzer-prize winning poet, is best known to popular audiences for her villanelle “One Art” (“The art of losing isn’t hard to master;/so many things seem filled with the intent/to be lost that their loss is no disaster”). Reading these books offers a matchless, non-linear path into Bishop’s creation and revision process. There’s also the pleasure of chasing references and mentions across letters and years.

Take 1965. Bishop had been living in Brazil with her lover Lota de Macedo Soares for almost fifteen years, and published her volume of poetry Questions of Travel, her first with Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. The first appendix of Poems collects selected unpublished manuscripts, so we see that in 1965, Bishop gifted an illustrated, hand-written poem to a friend that begins:

Dear, my compass

still points north

to wooden houses

and blue eyes,

fairy-tales where

flaxen-headed

younger sons

bring home the goose

A second version of the poem rearranges the stanzas into quatrains and was published posthumously in Edgar Allan Poe & the Juke-Box (2006), an assemblage of Bishop’s unpublished work and fragments edited by Alice Quinn, poetry editor of The New Yorker from 1987 to 2007.

In 1965, Bishop also sent a few letters to the poet Anne Stevenson, who wrote the first monograph of the writer, published the following year. Prose collects selections from their three-year correspondence about Bishop’s writing—in which Bishop speaks frankly about her family history and the influences on her work. It is a remarkably personal correspondence given that the two women never met. Bishop was pleased with Stevenson’s resulting book, which was, by 1965, nearly complete. She sent factual corrections to Stevenson, “all in the biographical part […] I must have written you awfully hurried and confused letters, like this one. The corrections are all just facts, nothing to do with your interpretations (very nice) or opinions, etc. about myself.” In a later letter, Bishop offers her condolences for Stevenson’s recent miscarriage, and remarks at “feeling how wonderful it is to have even one reader as good as you.”

Meanwhile, her correspondence with Robert Lowell, which had been ongoing for nearly twenty years, had settled into a comfortable mix of the professional and personal. She writes to him about a scare over Lota’s health and her debates with Robert Giroux over which poems to include in Questions of Travel. Lowell sent her a blurb for the volume, which reads in part, “She has a humorous commanding genius for picking up the unnoticed, now making something sprightly and right, and now a great monument.” Their mutual friend, literary critic Randall Jarrell, died in a car crash that may have been a suicide, and they consoled each other at the loss.

Her editor at the New Yorker was at this point Howard Moss, with whom she had, in Biele’s words, “a warm friendship but not an intimate one.” She sent him several requests for assistance in sorting out New Yorker subscriptions—for herself and friends—which he handled with good humor, even though, as Bishop noted, “this is scarcely your line of work and I do apologize.” Bishop sent him the poem “Under the Window,” in late September, and as was her wont, followed it a week later with a correction to one line. Moss replied that he was “overjoyed” to have the poem. In it, she describes a spring in Ouro Preto:

The water used to run out of the mouths

of three green soapstone faces. (One face laughed

and one face cried; the middle one just looked.

Patched up with plaster, they’re in the museum.)

It runs now from a single iron pipe,

a strong and ropy stream. “Cold.” “Cold as ice”

“Dear Elizabeth,” Moss wrote, “Here is a check for UNDER THE WINDOW, OURO PRETO, and thanks again for a poem I love.”

Bishop had described the same spring to Lowell in a letter posted in mid-September: “There’s a big spring that runs out just below the house—an iron pipe where there used to be a fountain—and everyone stops, always to have a drink there—dogs, donkeys, cars—besides all the pedestrians. Just now came a huge truck, painted pink and blue and decorated with rose-buds—On the bumper it says ‘Here I am, the one you’ve waited for.'”

In the poem, she writes:

A big new truck, Mercedes-Benz, arrives

to overawe them all. The body’s painted

with throbbing rosebuds and the bumper says

HERE AM I FOR WHOM YOU HAVE BEEN WAITING.

Images and characters echo across the volumes, and I can recommend no greater pursuit for an afternoon than hunting Bishop in her own words—watching her worry over household expenses or express exasperation over the latest political news. It is a delight to read the poet free from the critical frame that she so feared taking up.

Phoebe Connelly is a writer and editor in Washington, D.C.