In “Go Out and Burn Them,” one of the standout stories in Greek writer Christos Ikonomou’s Something Will Happen, You’ll See, a bereaved widower is found climbing into a public trash bin. “Any man who lets his wife die like that,” he tells the passerby who stops him, “deserves to go out with the trash. They can pick me up and recycle me, maybe I’ll come out a more useful man.” It’s a striking expression of guilt, but also a rather absurd one—there was nothing that the widower, Sofronis babra-Tasos, could have done to save his wife. She had a form of cancer that no doctor in Greece could treat. Indeed, it’s the country’s backward medical system that’s to blame.

But it’s precisely this feeling of helplessness, the doomed reliance on an incompetent, crisis-ridden state that has pushed Tomas over the edge. Like the other characters in this collection—whichis set entirely in the working-class suburbs southwest of Athens, and unfolds during the early years of the ongoing financial crisis—he is a lowly member of the Greek proletariat, forsaken by his country’s rapidly crumbling institutions. And like so many members of his country’s working class, he has turned to self-vilification as a way of processing the injustice he suffers.

This phenomenon of internalizing national rot, of transforming economic hardship into a personal shortcoming, also points toward Something Will Happen’s biggest accomplishment. A political novelist’s first and most serious challenge is to humanize his subject matter, and in this Ikonomou succeeds completely. You will find no references to rising inflation rates or growing unemployment in his stories, or to the right-wing New Democracy or the left-wing Pasok. Politics—and politicians—remain a cruel and indifferent presence off-stage. Instead, we encounter ordinary people who are, despite skyrocketing unemployment rates, trying to negotiate a mounting pile of overdue bills.

Which isn’t to say that the crisis plays an insignificant role in Something Will Happen. Far from it. Ikonomou’s stories often open with provocative allusions to the effects of Greece’s recession: “Another notification came today from the bank.” “Hunger woke him.” “Losing your job is like breaking a limb.” But the stories soon leave behind these gritty proclamations, focusing more on the subtle psychological impacts that poverty has on people and communities.

Troubling patterns emerge. Men often desert and even turn on their loved ones. In “Come on Ellie, Feed the Pig,” the title character’s long-time boyfriend absconds one night with all their savings—which amounts to a measly eight hundred euros—including the notes and coins that she saved in a piggy bank. “I don’t get it,” Ellie reflects, “If poor people do things like that to other poor people what on earth are rich people supposed to do to us.”

It’s a good question, one that can be asked of many of the book’s characters. Leftist union leaders betray their fellow workers; pregnant women are stabbed at corner stores; family members are reluctant to cough up money for a funeral. In “Placard and Broomstick,” a man tries to stand up for his best friend who had a fatal building-site accident while working overtime (steel cables; high voltage), and finds himself picketing alone, with a sign glued onto a broomstick. It is, he reflects, “the most pathetic, most ineffectual protest since the birth of the worker’s movement. Since the birth of the world.”

Save for the one-man protest, the dramatic events I’ve alluded to all happen off-stage. Indeed, Ikonomou largely eschews action, choosing instead to relay events via his characters’ memories and interior monologues. Narrated either in the first or close-third person, his stories read more like late-night confessions than conventional narratives. An economic crisis, Ikonomou recently said in an interview, makes “you want to close up to yourself and not care about other people,” and his formal strategies go a long way to convey just how isolated his characters are.

Yet Ikonomou does not simply rub our faces in disunity and despair. His characters might feel like they are suffering private tragedies, but Something Will Happen repeatedly calls our attention to the subtle human connections that remain. Ellie Drakou throws her husband’s belongings off the balcony in “Come On Ellie”; later, in “The Things They Carried”—an homage to Tim O’Brien—a character walking down the street is almost struck by a violin thrown off a balcony by a jilted lover. We, too, connect with the characters: The widower climbing into that trash bin has a minor role in the story “Mao,” but turns out to be the protagonist of “Go Out and Burn Them.”

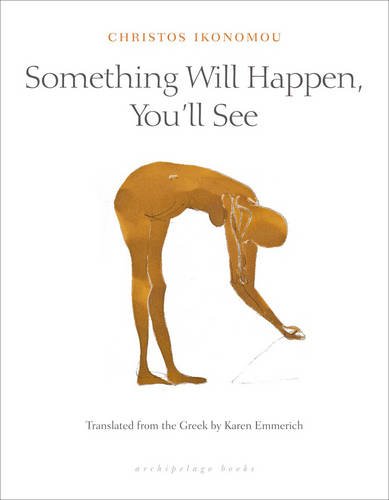

Karen Emmerich deserves special praise for her translation of Ikonomou’s charming, vernacular, and energetic prose. In an attempt to approximate the original Greek, she often leaves commas out of Ikonomou’s sentences, which reaffirms how urgent they are. The style gives the sense that the crisis continues on, uninterrupted. Ikonomou’s characters carry on, too, in spite of the dire situation that has convinced them of their powerlessness.

Ratik Asokan is a freelance writer based in New York. He writes about literature, film, and photography.