You know the story. A young Jewish man preaching in Galilee and Judea accrues a small group of followers. He annoys the Jewish establishment and the Roman occupiers enough to be executed by crucifixion. It is a demeaning and, for the time at least, unremarkable end, but soon afterward, his acolytes claim that his body has vanished from its resting place, and that he has appeared to them in visions. This, they say, affirms his identity as the Son of God.

For a while after this, the disciples and hangers-on of Jesus Christ—who believe that the world as they know it will end in a few months or years, certainly within their lifetimes—are relatively quiet, viewing themselves as disaffected Jews rather than the originators of an entirely new religion. The adherents to ‘The Way’, as their movement is sometimes called, proselytize and amass followers, but nobody writes much down or thinks about building any kind of institutional structure. What would be the point, with the apocalypse nigh? Several years later, Paul, a zealous Jewish persecutor of this vexing little sect, on his way to Damascus to do more persecuting, encounters a vision of Jesus Christ like the disciples before him. Paul becomes a traveling preacher and starts writing what we now know as the New Testament.

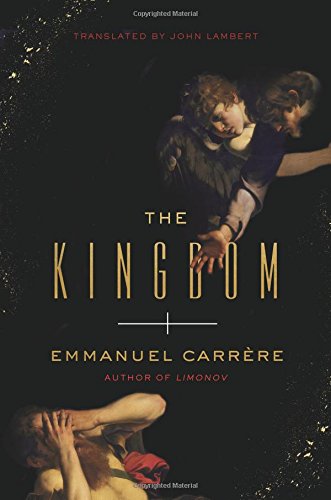

All this and more is covered in The Kingdom, the recent book by French screenwriter/author/intellectual-of-all-trades Emmanuel Carrère. (Among other things, he has written a true crime book called The Adversary, a biography of Philip K. Dick, and a strange meditation on a controversial Russian writer/political figure titled Limonov; he was also the co-creator of the cult French TV series The Returned.) The Kingdom, translated into English by John Lambert, is a weird, brilliant hybrid of biblical interpretation, memoir, and historical fiction in which Carrère scrutinizes his own wavering Catholic faith, and via close but undoctrinaire textual analysis speculates about the personalities and lives of the earliest Christians, filling in gaps in the historiographic record using his own imagination. There’s a lot going on in this book. It’s brash in its structure, tone, and some of its claims. But Carrère isn’t doing anything that Christians, wavering or otherwise, haven’t been doing for about two millennia. He’s just doing it an in a wildly contemporary, self-conscious way.

Carrère became devoutly Catholic during a depressive period in his thirties, under the influence of his godmother, who wrote a number of hymns that were adopted by the French Catholic church. After a few years, he drifted away from the Church—not because of a particular moment or crisis of faith, but through re-assimilation into his natural habitat of secular Parisian intelligentsia. The Kingdom is, in part, a Christian spiritual memoir, a genre which began in the fourth century with Augustine’s Confessions and which often gets conflated into the fuzzy-bordered genre categorization of “mysticism.” Granted, unlike Carrère, most Christian mystics have not, in their inward-turning examinations of spiritual life, found reason to discuss their family’s search for a suitable summer home (Carrère is pleased to finally find one on Patmos, the island where the John who may or may not be the John who was one of Jesus’s twelve disciples wrote the Book of Revelations), or their online pornography consumption (“Of course, the sites prefer to say that the girls are cheeky students who are in it for the fun, but most of the time you have your doubts”). And few have written in retrospect about their Christian life from their present perspective of non-belief, which Carrère is a little bit coy about until he’s about halfway through the book. Then again, Augustine wrote plenty about his sexual desires. And some Christian mystics come close enough to what we’d consider agnosticism that I suspect they’d have selected the “spiritual, not religious” descriptor on their online dating profiles. (I’m looking at you, Meister Eckhart.)

If you aren’t reasonably familiar with the New Testament, you can just as well skim the sections in which Carrère gets deep into the texts to opine about esoteric disputes, such as who exactly Luke spoke to as he traveled through Judea researching the life of Christ. More gripping are his speculations—sometimes pure inventions—about the lives and personalities of the Apostles who wrote the New Testament and their supporting cast of early Christians. Once again, Christians have done this for centuries—albeit, at least pre-Gutenberg, more through art than writing, a connection Carrère makes explicit in a moving passage in which he imagines how Caravaggio would paint the moment Paul started to dictate his first epistle to Timothy. Carrère’s mode of biblical interpretation is brilliant. When there are gaps in the texts, Carrère invents. We get convincing pages about Paul’s two years of imprisonment in Caesarea and Rome, a pivotal moment that is omitted from Acts of the Apostles (either deliberately or lost to time). We get vivid studies of minor characters who get short shrift in the canon. (Joanna, wife of Herod’s servant Chuza, we hardly knew ye.) As the jacket flap boasts, Carrère really does “[shoulder] biblical scholarship like a camcorder.” And he’s a genius cinematographer. Every zoom and pan gripped me.

At the heart of the book are the depictions of Paul and his sidekick-turned-frenemy, Luke. Paul is arrogant, cranky, and intensely doctrinaire in his interpretation of the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. He clashes with most of the other players in the story, as well as the Jewish establishment and the embryonic churches he devotes his life to founding (and then excoriating for not meeting his standards). Luke, on the other hand, is a little bit emo—a gentle Jew-curious Greek doctor with conciliatory instincts, whose interpretation of the religion he helps invent is more about fellowship than law, and whose understanding of Jesus centers on anecdote rather than Paul’s rigid abstractions. Sometimes Carrère forces this contrast a little bit, as if the screenwriter in him is responding to a studio note to “add more conflict.” This makes for a more satisfying story, even as it strains the historical record.

Underlying The Kingdom is the question scholars, both secular and non-, have attacked from every conceivable angle: How did this obscure Jesus cult become the dominant force in the Western world? The rise of Christianity, before Constantine put his massive finger on the scale by converting in 312 AD, is the longest long-shot in human history. It was a religion designed by and for the disenfranchised and poor—and unlike their many competitors in the spiritual marketplace of the Roman Empire, the early Christians celebrated their powerlessness. What’s more, their entire belief system rested on a miracle—a resurrection that happened in recent history—rather than an ancient, reified cosmology rooted in ethnic identification or the processes of the natural world. It must have been a pretty tough sell.

Carrère’s implicit answer is that Christianity thrived, and continues to thrive, because of the emotional power of its stories. By imbuing its early followers with lives and psyches, he shows us rather than tells us (to use another hack screenwriter term) how its central story, of a god who creates man in his own image and sacrifices his son for us, took hold. The book ends with Carrère’s visit with a volunteer group to a Christian home for the mentally disabled. There, as Jesus did for his disciples, they wash each others’ feet. Then they join the disabled residents—like the early Christians, the disenfranchised and poor—in a goofy celebratory dance. In that pure, joyous moment, Carrère once again glimpses the power of that story, and so do we.

Michael Sonnenschein is a television writer living in Los Angeles.