Certain writers are too weird to fully belong to their own time. Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky—a Soviet writer obsessed with Kant and Shakespeare, whose own life barely rippled beyond a small coterie of Muscovite writers before his death in 1950—is among them. Krzhizhanovsky wrote philosophical works of fiction that veer between chattiness and, in the fine translations of Joanne Turnbull and Nikolai Formozov, unexpected elegance. They are tales of bodies suspended between life and death, of an animated Eiffel Tower that rampages across Europe, and of towns where dreams are made literal. To read these stories is to be buttonholed by a slightly mad but unfailingly interesting stranger desperate for a sympathetic ear. In Krzhizhanovsky, we find the aphorisms of a dime store philosopher and the polyphony of a schizophrenic.

Krzhizhanovsky’s biography contains multitudes, though his polyglot identity was likely a handicap under the brutally homogenizing Soviet state. Krzhizhanovsky was born in 1887 to a Polish Catholic family in Kiev. In Ukraine, he studied law and worked for a brief time as a lawyer. But after the “lifequake,” as one of his characters cleverly describes the 1917 revolution, he moved to Moscow where he hoped to make his name as a writer. There, Krzhizhanovsky found a tiny room on the historic Arbat street, and treated his meager accommodations with a sense of optimism and mischief. In her introduction to Memories of the Future, a collection of stories published by NYRB Classics last year, Joanne Turnbull quotes a letter in which Krzhizhanovsky brags to a friend, “I’ve discovered a new way of successfully stretching out my legs while sitting at my desk.”

The line is archetypal Krzhizhanovsky: bright humor masking underlying despair. It also recalls “Quadraturin,” one of his best stories, in which a man applies a mysterious substance to the walls of his cramped room, only to watch it expand inexorably. By the story’s end, the protagonist finds himself trapped in a space that won’t stop growing. Cruelly ironic—a larger apartment is a blessing, an infinitely larger one is a curse—the story reflects the simultaneous claustrophobia and solitude of Soviet life.

In Moscow, Krzhizhanovsky wrote stories, plays, and theater criticism, as well as commentaries on Shakespeare and Kant, whose Critique of Pure Reason proved revelatory. (“Before it had all seemed so simple: things cast shadows,” Krzhizhanovsky wrote, reflecting on the philosopher. “But now it turned out that shadows cast things, or perhaps things didn’t exist at all.”) But although Krzhizhanovsky’s stories were well-regarded at readings, government censors repeatedly rejected his manuscripts, with the result that he never managed to publish a book in his lifetime. Maxim Gorky, the state-appointed doyenne of Socialist realism, dismissed Krzhizhanovsky’s fiction as “more suited to the late nineteenth century.”

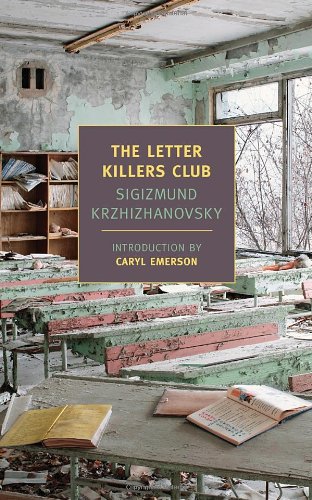

Soviet officials rejected Krzhizhanovsky’s oblique and strange novella The Letter Killers Club when he submitted it for approval in 1928. Although sometimes portrayed as a mild-mannered litterateur, Krzhizhanovsky had the audacity to challenge the book’s rejection. He was perhaps emboldened by the politics of the time—Stalin’s regime had yet to achieve its most murderous heights—and the fact that the chief censor, Pavel Lebedev-Polyansky, was also his boss at the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, where Krzhizhanovsky worked as an editor. Even so, his appeal was denied, spurring him to quit his encyclopedia job.

The Letter Killers Club is a representative but ultimately unsatisfying Krzhizhanovsky work. The novella is made up of stories-within-stories as told by participants of the titular group—a gathering of men who share improvised fictions they call “conceptions.” Believing that “libraries have crushed the reader’s imagination,” and that “the professional writings of a small coterie of scribblers have crammed shelves and heads to bursting,” they forbid anybody from writing their stories down. In articulating the problem of inherited literature, that literature represents a crisis that must be overcome, Krzhizhanovsky anticipated Harold Bloom’s “anxiety of influence” by a half century. And while the Letter Killer gatherings have the air of something occult—the men, for example, have peculiar, one-syllable code names—they are also an attempt to return fiction to its roots in oral storytelling. “Everyone has the right to a conception,” one club member instructs a newcomer, “both the professional and the dilettante.”

Framed within the narrative of a disinterested outsider brought in to observe the gatherings, the stories play out over seven spare chapters. There isn’t much to link them, but they are rich with allusion—to Shakespeare, the Bible, continental philosophy, Greek and Roman poetry. In one “conception,” a short play splits some of Hamlet’s peripheral characters into twins (Guilden and Stern, for example), eventually leading to a kind of endless recession as various actors vie for parts and, later, for the parts of actors playing those parts. Another story is set in a futuristic dystopia in which a small elite uses machines and a biological agent to control the population’s movements. Later tales feature a vagabond priest and ancient Roman funeral rites.

The Letter Killers Club has much of what makes Krzhizhanovsky appealing—it is fascinatingly odd and, at times, quite well-written—but it never coheres into anything larger. To borrow the title of one of the author’s short stories in Memories of the Future, it gestures at “someone else’s theme” without ever planting a flag. Censorship looms, but on a distant horizon; there are intimations of trouble within the group, but save one act of violence, little happens. Were Krzhizhanovsky to have fleshed out the frame narrative, we might have been left with a haunting account of artistry extinguished by the state, for there is a sense here—alas, one left all too vague—that a dangerous force monitors these men when they leave their gatherings. As it is, that story belongs to Krzhizhanovsky himself; he lived it.

Jacob Silverman‘s work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The New Republic, and other publications. He is also a contributing editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review.