Los Angeles Times book critic David Ulin would readily admit that what, how, and why one reads inevitably change over time. What concerns him is that the act of reading is itself now being changed by the times. The quiet space we require for reading “seems increasingly elusive in our over-networked society,” he writes, “where … it is not contemplation we desire but an odd sort of distraction, distraction masquerading as being in the know.” I have suffered from a form of this allergy to deep engagement and its corollary need for “information”; for the better part of the past decade I mostly engaged with books indirectly, distractedly, through journalistic reviews of the kind Ulin writes so capably. If I counted up the words I read about, say, Don DeLillo’s Falling Man, I probably could have (and should have) read the book itself. But I digress and perhaps overshare—other symptoms, Ulin suggests, of the age.

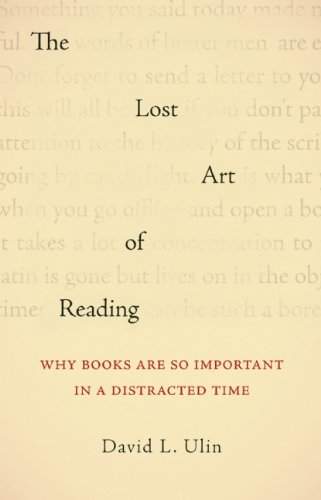

The Lost Art of Reading expands upon an essay Ulin published last year, and though pocket-size and only 150 pages, the book attempts to weave together several narrative threads. It is a personal essay recounting the author’s longstanding literary enthusiasms (Joan Didion, Alexander Trocchi) and his experiences as the father of a teenage son. It is a journalistic summary of recent commentary on e-readers and the neuroscience and psychiatry of attention. And though Ulin recognizes that “literature doesn’t, can’t, have the [cultural] influence it once did,” the book is also what its title advertises: a paean to the intimacy and attention demanded of book readers, and the sense of empathy that develops from engaging with books. The first two threads at times feel like filler, especially when Ulin draws liberally from still-current titles like Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, Eva Hoffman’s Time, and David Shields’s Reality Hunger: A Manifesto. Yet, as one might expect of so dedicated a reader, the final argument is cogent. Particularly strong is his elucidation of the political fallout of our “distracted time.” Using the momentousness of the 2008 presidential election as a “frame” (one of his favorite terms), Ulin channels and deploys Didion’s 1968 essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” to speak clearly of a “comprehensive dissolution, in which the very idea of a common ground, or common narrative, has been rendered obsolete.”

Books like The Lost Art of Reading, however, face a fundamental challenge. It’s one thing to explain what is good or bad about a particular novel or nonfiction title, as Ulin does week in and week out for the Los Angeles Times. But the transactions between author and reader he attempts to describe here are so unique that descriptions of them are necessarily vague. Ulin ends up saying: “This is what literature, at its best and most unrelenting, offers: a slicing through of all the noise and the ephemera, a cutting to the chase.” And: The process of reading “is (or should be) porous, an interweaving rather than a dissemination, a blending, not an imposition, of sensibilities.” Well, yes, but such statements rely heavily upon just the kind of empathy and engagement he praises. The self-selecting audience of The Lost Art of Reading—or, for that matter, any hymn by Alberto Manguel—can make concrete such abstractions by reflecting upon its own experiences with literature. Books like this remind readers why they do that now-idiosyncratic thing they do. Turning browsers into dedicated readers, to say nothing of figuring out how to counter the distractions of the times, seems an altogether more complicated task.

Brian Sholis is a writer and editor living in New York.