In 1937, her father moved the family to an all-white neighborhood in Chicago to deliberately challenge the constitutionality of racial restriction clauses. In response, a white mob gathered and threw a brick through their window, narrowly missing eight-year-old Lorraine. The Hansberry case moved through the court system, with the Supreme Court of Illinois upholding the legality of restrictive covenants and forcing the Hansberrys out of their home. The case then went all the way to the United States Supreme Court in Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940), which reversed the lower court’s decision without providing a more general ruling on the constitutionality of such covenants. Not long after a failed bid for Congress in 1940, Hansberry’s father bought a house in Mexico and prepared to move the family out of the United States. As Hansberry herself put it in her interview with Lillian Ross, “Although he had tried to do everything in his power to make it otherwise, he felt he still didn’t have his freedom.” He died in Mexico in 1946 before his family could join him. According to Hansberry, “American racism helped kill him.”

In Hansberry’s early interviews, interviewers often focused on this story as the inspiration behind Raisin, while describing Beneatha—the younger sister who wants to use her father’s insurance money to pay for her medical degree—as a stand-in for Hansberry. Hansberry, however, was always quick to complicate such claims. Although she frequently admitted that Beneatha was something like herself “eight years ago,” she also compared herself to George Murchison, Beneatha’s American suitor, and described Joseph Asagai, Beneatha’s Nigerian suitor, as her “favorite character” and the play’s most “sophisticated figure.” Hansberry was also quick to point out the sharp difference between her relatively affluent middle-class background and the working-class background of her characters. Rather than focus on her own “atypical” experience, she consciously chose to portray a family whose experience she considered “more relevant” to “our political history and our political future.” While some critics have argued that Hansberry “never fully resolved the duality of her life and works—upper-middle-class affluence and Black heritage and revolution,” Hansberry’s interviews suggest that she openly acknowledged and embraced these tensions. Prefiguring contemporary understandings of intersectionality, Hansberry would insist on the racial, regional, cultural, economic, and gender specificity of the experiences depicted in her play. At the same time, she often articulated a Pan-African sensibility—a sense that Black people of all classes and nationalities were united by their oppression under global white supremacy and should look to one another for paths toward achieving their liberation.

Hansberry’s sense of the complexity within and connections across Black communities reveals itself in her interviews in many ways. In “An Author’s Reflection,” Hansberry would describe it as a dramatic fault of her play that “neither Walter Lee nor Mama Younger loom large enough to monumentally command the play.” And yet, as she shared this observation with interviewers, she would go on to observe that this “weakness” in her play might, in fact, be a strength: “When you start breaking rules you may be doing it for a good reason.” She flatly rejected certain interviewers’ efforts to see individual characters as representative of the race, pointing instead to the ways in which her characters enabled her to draw out different sentiments within the Black community. It was this, indeed, that drew her to the dramatic form. As she put it, “I’m particularly attracted to a medium where . . . [you can] treat character in the most absolute relief—one against the other—so that everything, sympathy and conflict is played so sharply you know—even a little more than a novel.”

Just as Hansberry refused her reviewers’ and interviewers’ efforts to see her characters as monolithic representations of “the race,” she also resisted their efforts to whitewash race entirely out of the play. Hansberry clearly stated that she saw her characters as fundamentally different from the stereotypical representations of Black people that dominated the stage. In one particularly contentious dialogue with Otto Preminger—the director of Carmen Jones (1954) and Porgy and Bess (1959)—Hansberry described those films as “bad art” because the stereotypes therein demonstrate that “the artist hasn’t tried hard enough to understand his characters.” Many audiences understood that Hansberry’s characters were different from such exoticized and stereotypical representations; nevertheless, they often deeply misunderstood the significance of that difference. In interview after interview, Hansberry was asked to comment on the common but deeply racist refrain that hers was “not a Negro play at all, but a play about people.” Over and over again, and with truly remarkable patience, Hansberry pointed out that this was, in fact, “a misstatement”—that her play was both “a play about people” and “a play about Negroes,” and to “get to the universal you must pay very great attention to the specific.” Against the racist fictions of her time, Hansberry insisted not only on the obvious humanity of Black people, but also on the historical construction of all human experience. As she put it, “Virtually all of us are what our circumstances allow us to be.”

Hansberry also repeatedly refused reviewers’ and interviewers’ efforts to oppose protest to art, or their efforts to single her work out as exceptional. To those who complimented her for rising above protest, she would respond: “My play is actively a protest play, actively so. There is no contradiction between protest and art and good art. You know, that’s an artificial argument.” She would also insist—though occasionally to nonlistening ears—on the obstacles that stood in the way of Black playwrights seeing their work staged and appreciated in its fullness and complexity. As her interviews turned more and more toward the political issues of the day, she expressed this support for other Black writers’ and activists’ works by appreciating the value of any and “all ideologies which point toward the total liberation of the African peoples all over the world.” When pushed as to whether she considered herself an integrationist or a revolutionary, she simply replied, “The latter may be necessary to make the first possible.”

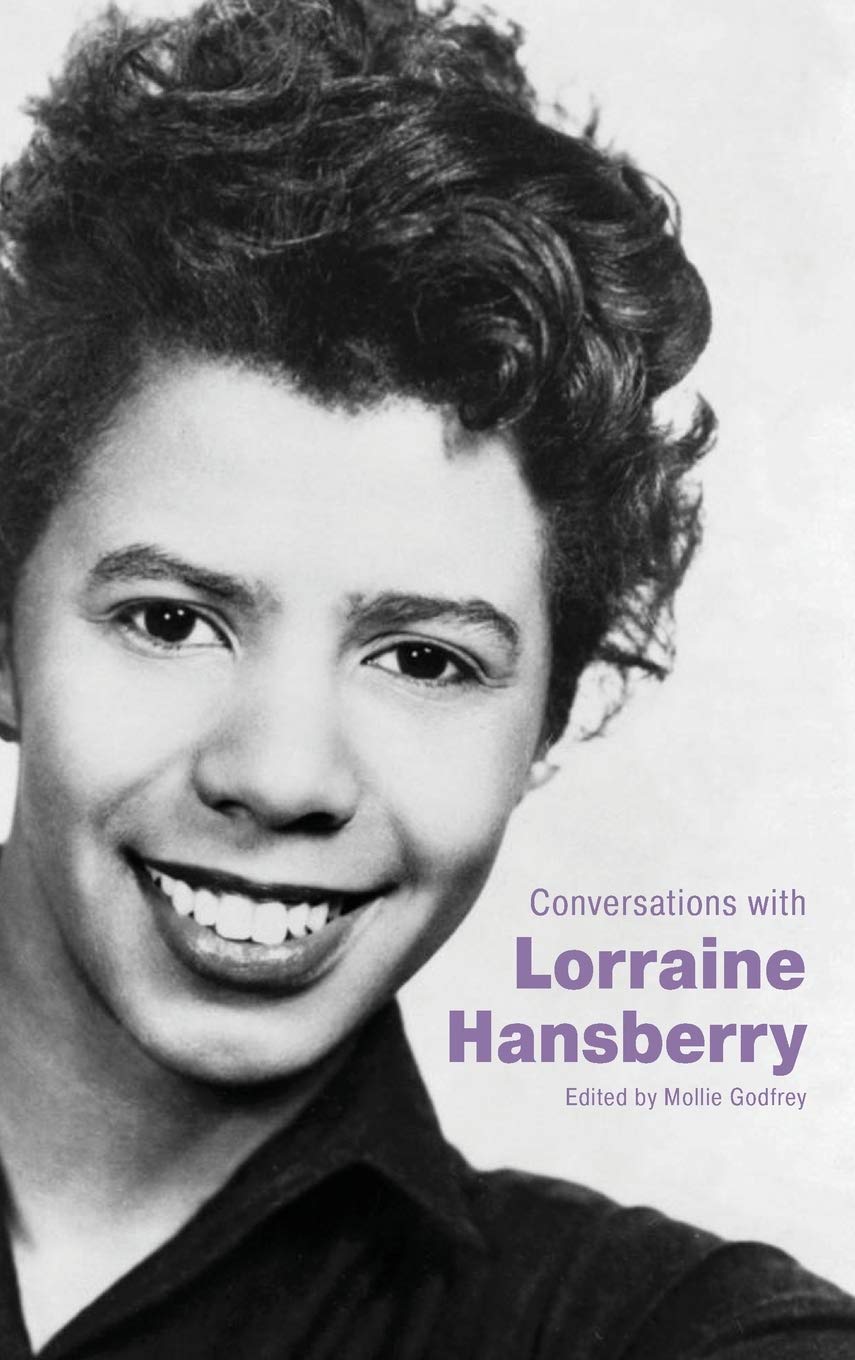

Excerpt from “Introduction” to Conversations with Lorraine Hansberry edited by Mollie Godfrey, Copyright © 2020 by University Press of Mississippi, is reproduced by permission of University Press of Mississippi. All rights reserved.