Somewhere at the intersection of practical science, high art, dorm room philosophy, and idiosyncratic star-making exists the journalism of Lawrence Weschler, a longtime New Yorker writer and the current head of New York University’s Institute for the Humanities. As a sculptor of his own career, he has never been afraid to pithily brand what it is he does. In the 2000s, McSweeney’s began publishing a series of unlikely but oddly compelling visual rhymes under the rubric of “convergences.” In the ’90s, when he was engaged deeply in political journalism, he explained that he was shuttling between “cultural comedies and political tragedies.” In the ’80s he referred to his profiles as “passion pieces.” He defined his subjects as individuals touched by the hand of grace whose lives proceed as such:

One works and works at something, which then happens of its own accord: it would not have happened without all the prior work, true, but its happening cannot be said to have resulted from all that work, the way effects are said to result from a series of causes.

Similarly, one must examine Weschler himself not from the perspective of his intentions but his effects: His attentions have a way of magnifying the achievements of those he writes about into a kind of generalized intellectual acclaim. For example, his first book, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin was published in 1982. In 1984, Irwin was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called “genius” award, becoming the first visual artist to do so. Which leads one to wonder: Is Weschler a kind of bookish and benign Svengali?

His recent work certainly indulges in this star-making tendency and that includes his new collection, Uncanny Valley. As for the writing, you might plot your tolerance for it against your reaction to this typical set-up passage, a perceptual experiment meant to illustrate the brain’s ability to erase the inconvenient detritus of the human face to achieve perfect stereoscopic vision:

Okay, try this: Closing your right eye, gaze to the right with your left . . . Notice how your nose, looming huge, blocks a good part of the view in that direction. Now, shift eyes: closing your left eye and peering left with your right. Same thing. Pretty obvious. Only, now, with both eyes open, gaze right, and notice how your nose pretty much disappears from your visual field, even though your left eye is in fact clearly taking it in…. Once again, your brain, your visual cortex, suppresses the thing it doesn’t need to see (the nose) and weaves together a continuous, undifferentiated vantage.

This appears in a long profile of twin brothers Trevor and Ryan Oakes, a still-obscure pair of visual artists who he profiled for the Virginia Quarterly Review in 2008. The piece argues that the Oakes twins’ quasi-scientific research is trailblazing a bold path compared to contemporary artists more enraptured by the market; the case is made that they’ve thrown into doubt the authority of Renaissance perspective. Their tools? A series of jerry-rigged drawing aids based on the Mercator projection and the camera lucida. The work? A series of trippy, albeit academic, drawings that illustrate how humans actually see. I found the profile . . . cool, perhaps more so than the work it depicts. Whether you’ll find it similarly engaging depends—mostly on your tolerance for writers who burnish their subjects to the point that the writing outshines the underlying thing being written about.

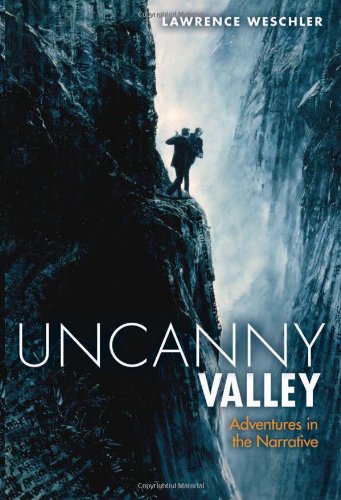

If it’s unclear, I’m a diehard Weschler fan. However, if you’re unfamiliar with his past work and uninterested in tracking the linkages between his maddeningly broad range of subjects, Uncanny Valley may frustrate you. Herein, the author profiles a seemingly random succession of minor artists and major political events, each work and document, procedure and process, described in loving and microscopic detail. There is a New York Times Magazine piece about filmmaker Bill Morrison and his re-edit of decaying celluloid film stock into a mysterious motion picture poem, then a brief New Yorker article about Italian playwright and future Nobel laureate Dario Fo’s whirlwind tour of Broadway shows. Suddenly, the canvas goes wide with a piece about the politicking surrounding the founding of the International Criminal Court, and in the next, the focus will narrow, your attentions whipsawed onto an essay spiraling in on author’s own naval. Early in the book, a series of seven short, self-conscious interludes track Weschler’s subjective experiences with, among other things, Richard Serra’s Torqued Ellipses; “Popocatepetl,” a novelty composition by the author’s grandfather, Ernst Toch; and, get this, the moths drawn to the towers of light set up near Ground Zero as a September 11th memorial.

The first thing you’ll notice in all of these pieces is that Weschler is very enthusiastic about the topics he covers. Cultural critics tend to exist on a continuum of polarized emotion about their chosen subject—either enraptured or disillusioned with the work they’ve lavished so much, maybe too much, time and thought upon. Or, to put it in terms any New Yorker aficionado would understand: Pauline Kael is at one extreme; Anthony Lane on the other. Weschler is on the far end of the rapture scale. For him, a pair of unknown artists like the Oakes twins, or a mid-career painter like Vincent Desiderio are not just subjects, they become muses-slash-protégés whom he will justify to the world. (Exhibit A: Eerily coordinated with Uncanny Valley’s publication date, the Oakes Twins just closed an exhibit at Chelsea’s CUE Art Foundation which was curated by Weschler. Exhibit B: Their next stop is a residency at Los Angeles’s Getty Center to draw in the gardens created by Robert Irwin.)

Yes, it’s fascinating to read about artists who haven’t been overly dissected by journalistic groupthink, but anyone who believes in objective reporting and a non-interventionist press corp might cringe at how Weschler’s own discourses on art-making competes with the art itself. For the rest of us, the sheer variety of his enthusiasms may leave the reader breathless and struggling to discern any organizing principle.

Before dismissing this approach, however, let me advocate for his larger project. First, I’ll recommend you start elsewhere, if you hope to apprehend it—perhaps his slim volume on money-artist J. S. G. Boggs, or Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder, his Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award-nominated book about Los Angeles’s bizarre, is-it-real-or-is-it-fake Jurassic Museum of Technology. Or, in true Weschlerian fashion, start from the start with his first published work, Seeing Is Forgetting, about the above-mentioned Robert Irwin. By my (and many others’) estimation, it is the best book ever written about a visual artist and a Rosetta Stone for his later work. (Perhaps, too, an albatross?)

A perfect introduction to Weschler’s universe of the perplex, it “has convinced more young people to become artists than the Velvet Underground has created rockers,” according to Michael Govan, former head of the Dia Foundation and current director of the Los Angeles County Museum. What makes this book so enticing is his method of depicting both art object and maker in the same frame, at once daunting and approachable. First, he’ll dissect a recondite or opaque work in terms that are one part advanced graduate philosophy seminar, one part spellbound auctioneer. Next, he turns around to profile the artwork’s maker in intimate, casually glamorous terms familiar to the readers of celebrity profiles in People magazine. The results are portraits that are both admiring and aspirational.

Indeed portraiture—favorable to the sitter, truly unfavorable details conveniently forgotten—is probably the best way to explain the position Weschler’s takes vis-à-vis his subjects. For example, Seeing is Forgetting begins by narrating Irwin’s evolution from near-juvenile delinquent to forward thinking abstract painter to demateralizer of art objects. Yet, in a funny inversion of a typical origin myth narrative, his early hobbies are valorized while his later intellectual pretensions are joked about. Irwin’s adolescent interest in multi-coat, enamel-like paint jobs on classic cars is depicted as a foundation for west coast Minimalism’s “finish fetish”; his later preoccupation with phenomenological philosophers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty are portrayed as intellectual dalliances—vital to the work but out-of-character for a man who wrestles with a kind of “macho ignorance.”

The idea here is that if Irwin is willing to take a deep dive into French theory then even you, dear reader, are smart enough to give it a try. To read Weschler is to understand that an artist’s pop-cult obsessions are often profound, while their more high falutin’ interests might be less daunting and Ivory Tower than they initially appear. Essentially, Weschler grants the handiwork of “fine” artists an approachability which high art has lacked since modernism cleaved a line between high and low culture in the early twentieth century.

If there is one unfortunate trend to Weschler’s own career it is that, recently, the Svengali has been choosing less-promising pieces of clay. Sure, he still engages with frequent foils like painter David Hockney and film editor Walter Murch. (Murch plays a major role in one of Uncanny Valley’s better pieces.) But just as Tom Parker is nothing without Elvis Presley, and Tony Wilson nothing without New Order, one suspects Weschler’s own estimable talents would be better utilized in depicting the career of artists like Gerard Richter or Matthew Barney in all their inscrutable glory, rather than a comparative unknown. As an enraptured fan I’ll continue to read everything he does; as a slightly embittered critic, I’d challenge him to find more subjects who will not only benefit from his deep dives into their creative process, but will drive Weschler’s own process deeper still.

Alec Hanley Bemis started the Brassland record label, manages musicians, and has written for the New York Times, the New Yorker, and Stanford University’s Arcade blog.