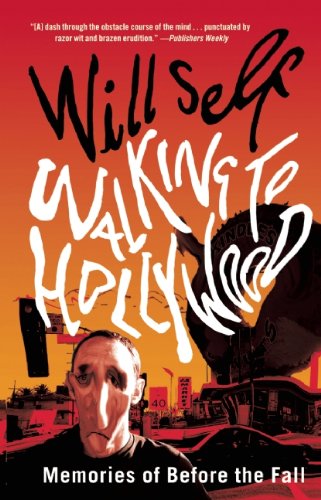

Once-roguish writer Will Self has come a long way from his days of bragging about snorting smack in the toilet of Tony Blair’s jet. His latest dispatch, Walking to Hollywood, sees the Brit-lit luminary blending a real-life non-narcotic obsession, urban psychogeography (the notion of walking as a subversive act), with his usual sesquipedalian flights of comedic fiction. But where his serrated satirical voice in 2009’s story collection Liver (mostly about habits that led to the detriment of the titular organ) sliced through page after page with deadly precision, Walking to Hollywood’s simplistic critique of twenty-first century culture cuts with a dull uncertainty of purpose. Thirty-year-old postmodernist critical theory uncomfortably poses as fiction, while glib memoir morphs into acid-casualty comic-book fantasy—all set loose on a winding 450-page journey toward a philosophical dead end.

This novelistic road to nowhere is founded on Self’s passion for non-fiction reports of walks in non-pedestrian-friendly places; yet along the way, we find him accompanied by characters and situations that could only be figments of his hyperactive imagination. In the beginning, we find “Will Self” on geographically blurred wanderings through England and America while accompanied by a foul-mouthed dwarf artist. Here we’re reintroduced to Self’s obsession with human grotesquerie (see his novel Great Apes), extremities of size and scale, and the adverse psychic effects of an endless crush of man-made consumer clutter. The “Walking to Hollywood” section is a surrealistic pedestrian trek under the pretense of discovering “who killed the movies.” As it turns out, the movies have killed reality: Self’s re-imagined version of LA is swept up by a mass illusion in which everyday people—Self included—are portrayed by famous actors and trailed by camera crews. And any concessions Self makes to realistic observation of LA’s urban spaces are eventually annulled when he gives himself temporary Incredible Hulk-like superpowers and begins overturning cars on the freeway. Later he takes a “walk of erasure” in Yorkshire, where the onset of amnesia acts as a welcome psychic cleansing. Again, what begins as an adventure in distorted reality eventually bleeds into pure fantasy, as Self ends up playing checkers with the Grim Reaper and meets a monstrous Struldbrug from Gulliver’s Travels.

Gonzo-journalism-inspired as it is, this faux-autobiographical, fictional travelogue also shares a suspiciously similar conceit with W. G. Sebald’s novel Vertigo, a work also marked by aimless peripatetic adventures and inscrutable black-and-white photos. But where Vertigo is about the instability of memory, Self’s hip nihilism advocates the total erasure of memory as the only way to successfully confront contemporary society. And where Sebald’s utilitarian prose comes in battleship-gray hues, Self has no qualms about stuffing words like “neurofibrillary” and “birefringence” into a sentence. Both books make overtly antisocial statements via their respective protagonists’ increasing alienation from the people, places, and events in a culture they can no longer comprehend.

Of course, Self is still capable of verbal virtuosity beyond just sounding like some mutant offspring of a Webster’s Unabridged and a Roget’s; but such sparkling similes as “He loped on ahead, his life story trailing over his shoulder like the silk scarf of a valiant fighter pilot…” seem random here—nice phrases plopped in the middle of banal rants. We mostly get rapid-fire referencing of mundane consumer-culture signifiers: an overkill of not only medical, technological, pharmacological, and scientific terms but also brand names, silly neologisms, and unnecessary italics.

Despite applying his usual experimental bravado, Self’s latest “novel of ideas” can only manage a miniscule peep of a postmodernist critique on the increasing unreality of our reality. Ultimately, Walking to Hollywood isn’t funny enough to make for good satire, yet it’s too cartoonish to take seriously.

Michael Sandlin has written about books for the Village Voice, Time Out New York, and many other print and online publications.