WHEN BARBARA SMITH describes Toni Morrison’s Sula as an “exceedingly lesbian novel” in her pathbreaking essay “Toward a Black Feminist Criticism,” she stops just short of calling either of the book’s main characters the L word. Sula, which sumptuously tells the story of a pair of Black girls learning how to become Black women in a world that aims to constrain their desires, reveals the depths of intimacy available to women when they focus on cultivating relationships with each other rather than seeking communion with men. For Smith, a woman deriving pleasure for herself “functions much like the presence of lesbians everywhere to expose the contradictions of supposedly ‘normal’ life.” In other words, to be a lesbian novel with no lesbians is to do the trenchant work of provoking readers to consider erotic arrangements outside of those deemed acceptable by heteropatriarchy by any means necessary.

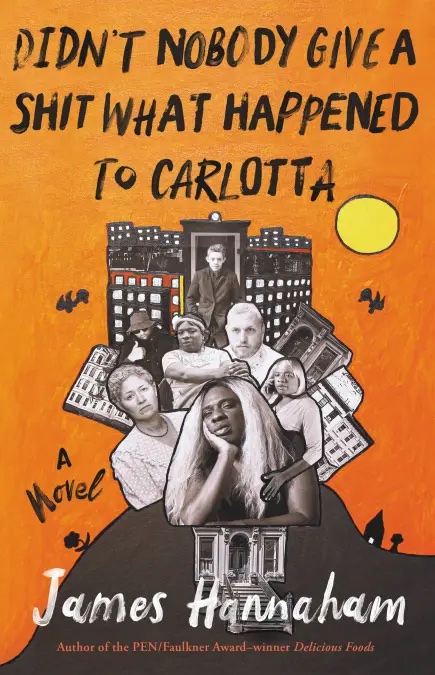

Though Smith finds reading Sula to be a profoundly rewarding experience, as a Black lesbian, she still entreats for “one book in existence that would tell me something specific about my life.” I returned to this tension between the specificity of being a lesbian and the expansion of the term “lesbianism” as I read the latest novel by James Hannaham. In Didn’t Nobody Give a Shit What Happened to Carlotta, Hannaham introduces readers to Carlotta Mercedes, a Black trans woman who—having just been granted parole after a year of pretrial detention and then twenty years of a twenty-two-year-sentence in a men’s prison in upstate New York—returns to her old stomping grounds in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, in 2015. Much of the novel takes place in the twenty-four hours after Carlotta’s release, and its style, which abruptly toggles between free indirect discourse and unmediated access to Carlotta’s thoughts and speech without any punctuation to signal the switch, crackles with a deeply felt urgency as she tries to make sense of a new world that has been so quickly built upon the old one. (If this sounds reminiscent of James Joyce’s modernist behemoth Ulysses, in which a wandering Leopold Bloom takes twenty-four hours to peregrinate around Dublin, it is. In a recent interview, Hannaham describes how he dealt with realizing that he was “low-key rewriting The Odyssey” by turning to Irish modernism.)

Given this synopsis, one might expect a gentrification novel, a prison novel, a trans novel, or simply an imitation of Joyce. Hannaham manages to avoid these generic conventions—for better and sometimes for worse—by exceeding them. To read Hannaham, a Black queer writer himself, is to encounter and explore a mind that takes irreverence seriously. In his first foray into literary fiction, God Says No, a religious Southern Black man brings the sacred and the profane into contestation by navigating his marriage to a woman while also seeking to satisfy his yearning for the company of men. Delicious Foods, which won the Pen/Faulkner Award for Fiction, quite uproariously brings together three harrowing characters: a woman held captive on a Southern farm, a son who has lost both of his hands, and crack cocaine, which gets its own sassy identity and speaking voice. In both novels, Hannaham wields earnestness and satire to make readers see what they thought they understood through a kaleidoscope of his invention.

In this way, Didn’t Nobody fits squarely within Hannaham’s body of work. Brusquely funny and subtly devastating, the novel is often quite playful even as it’s levying shrewd critiques of evils ranging from mass incarceration (“You build a whole buncha high-tech prisons, hire a shitload of COs, and it’s like . . . Field of Motherfucking Dreams, yo. They build that shit, so somebody ass gotta come”) to being misgendered (“Now, if what you want is some shit called ‘a father,’ then either you gonna have to change yo concept of what that mean, or you gonna have to recanize that what you see is what you get, sucka, just like Geraldine useta say”). Even so, as Black trans aesthetics continue to largely be forged through poetics, visual art, and memoir rather than fiction, to ask one day in the life of Carlotta Mercedes to make significant inroads in the representation of Black trans life might be one thing too much to ask of a novel with so many weighty concerns.

Take the deceptively simple idea of freedom, one of the book’s principal subjects. Carlotta has been incarcerated for twenty-one years for the crime of witnessing her cousin commit armed robbery and not doing enough to stop him. It takes five interviews with a parole board before Carlotta is granted early release just months shy of the maximum sentence that was originally ordered. It then takes five months after that hearing for Carlotta to be let out of prison. And then it takes five minutes after being dropped off in an Ithaca strip-mall parking lot to begin voguing and twirling toward freedom with $45 in cash and a check worth just north of $500 in her pocket. When she arrives in Brooklyn to begin her new life, however, the chaos of the city immediately places Carlotta’s highly conditional freedom in jeopardy.

To call parole a freedom at all when the most basic services are withheld and/or denied to those with criminal records should sound farcical. As Carlotta’s parole officer explains, to be released early from prison is to enter into a severely one-sided contract wherein parolees promise to avoid trouble while the state actively tries to keep them from fulfilling that promise with unnecessary hoops and unfair restrictions. In a few respects, Carlotta’s situation is as ideal as one can be upon reentry: she must refrain from alcohol (the armed robbery took place at a liquor store, after all), follow a curfew, and find stable housing and employment. Many of the difficulties of returning from prison are at least partially mitigated by moving back into her childhood home, a four-story brownstone still owned by her family.

But, if Fort Greene has changed since 1993—and reader, it has—much of that transformation escapes Carlotta as she deals with the chaos of a party being thrown for her in her deadname’s honor, a fete that also serves to commemorate her eight-year-old niece’s singing talents and turns into a bizarrely raucous July 4th party-cum-wake the following day. All the while, as Carlotta evades the vices that would send her back upstate and magically manages to procure a job driving an Access-A-Ride bus without knowing how to drive, it is the changes in her immediate circles that occupy her much more than the scale and speed of the racial demographic shifts that have occurred since the PBS program Ghostwriter portrayed the neighborhood as one full of all kinds of diversity decades prior.

So much seems to have transformed while Carlotta was away. Her son has grown up and grown out of his birth name of Ibe in favor of Iceman. Her mother, who gave up speaking Spanish openly so that she could use the language to gossip surreptitiously around (and about) her family, can no longer speak at all. The brownstone itself seems to have been renovated, though Carlotta cannot describe exactly how. These shifts in identity that invariably come with time for everyone and everything rarely serve as a point of connection between Carlotta and those she tries to reacquaint with, some of whom she is meeting for the first time after she has transitioned, a process she began within a year and a half of being incarcerated.

Relationships in this novel are built by way of shared experience more than anything else. Carlotta reinvigorates a friendship with an old pal named Doodle after they tell each other traumatic stories of being women with histories of sexual assault. She attempts to understand what is going on with her brother—whom she not-so-affectionally calls “Thing 2” and who spends his time alone in his room playing video games—by remembering the time she spent in solitary confinement. Though she cannot fathom what it means to voluntarily choose to live with little meaningful contact with others or the world, especially when the first floor of their home basically functions as a community center and boozy social club, she remarks that she has to respect how people evolve over time, even if “I guess stupid me’s always thinking people oughta be changing for the better.”

Rapidly, the entire situation becomes untenable. After bobbing and weaving from illegal or parole-restricted activity around her family and friends all day, Carlotta succumbs to a good time, gets drunk and high on Coney Island, passes out on the beach, and is unceremoniously taken back to jail. In the novel’s final chapter, Hannaham hits his full Joycean stride, taking inspiration from Molly Bloom’s soliloquy and giving Carlotta free rein to let loose, at full volume, her own stream of consciousness. Returning to New York for the second time, she theorizes freedom yet again as a set of conditions that allows one to opt into the fullness of life rather than opt out of aspects of it periodically for safety. Without the constraints of parole, Carlotta imagines a future in which “finally it feel like somebody seen me, the real actual Carlotta me, the me inside me, for the first time after forty-hmm-hmm years in a pain.”

Arriving at this ending, one may wonder to what extent Didn’t Nobody has been trying to be a Black trans novel, if it has been trying to be one at all. Carlotta’s life before prison and her transition, which might have been a focal point in a different novel, happens out of frame in this one. In her New Yorker review of the recent reissue of Imogen Binnie’s magnificent book Nevada, Stephanie Burt relishes in the extent to which Binnie participates in acts of refusal: “no to the standard Trans 101 narrative, in which before transition, we’re all suicidal and, after transition, we’re all happily indistinguishable from cisgender people, unless we become doomed sex workers; no to the expectations that books about trans people written for cis people usually meet.” Hannaham, though cis, certainly bucks tradition by rendering his protagonist as a complicated human rather than a stereotype. This is admirable but a tension similar to the one Barbara Smith locates in the difference between living as a lesbian and writing within lesbianism arises in representations of trans experience written by cis authors. There might be no satisfying resolution to this conundrum yet, but, before a Black trans novel tradition has been firmly established, the Carlottas that we are given might finally force more of us to actually give a shit about them.

Omari Weekes is an assistant professor of English at Queens College, CUNY.