She is biting her nails when I open the door, her purse pressed tightly against her breasts. As usual, I think as she walks in, head down, and sits in her usual place, Mondays and Thursdays, five o’clock: as usual. I shut the door, walk over to the armchair in front of her, sit and cross my legs, making sure I pull up my pants first so they won’t have those awful creases on my knees. I wait. She doesn’t say anything. She seems to be staring at my socks. Slowly, I pull a cigarette out of the pack in my coat pocket, then tap it on the arm of the chair as I search for a lighter in my back pocket. Before lighting it, I think again that I should stop using plastic lighters, disposable. Someone told me they-are-nondegradable-and-I-should-care-more-about-the-environment. I can’t remember who, when, where, or why. I play with the evil lighter between my fingers. Then I light the cigarette. She finally says:

“I’m sorry, but I think you’re wearing mismatched socks.”

Usually, a cigarette lasts from five to ten minutes. I try to spend as much time as possible on things like shutting the door, fixing my pants, thinking about lighters and eco-friendliness, so that she usually only gets to say something once I’ve finished my first cigarette. Almost always after I’ve asked very cautiously what she’s thinking about. Only then she sighs, looks up, looks me in the eye. This time, however, she doesn’t sigh. I consider telling her that I woke up too early, in the dark, and that . . . Instead, slowly, I ask:

“And does this bother you?”

She tenses her shoulders, and they go up almost to her ears.

Then she releases them slowly, as if massaging herself.

“It’s not that it bothers me, it’s just—Look, honestly, I don’t really care about your socks.”

She lets out that last sentence quickly, as if she’d wanted to get rid of it, to see what I’d say. But I don’t say anything. I limit myself to taking a drag on my cigarette, flicking away the ashes. I steady my glasses on my nose, these frames need to be readjusted, always sliding down. Ashes fall on my pants. I wet my index finger and thumb in order to remove them, throw them in the ashtray. She waits. I stare at her. She stares at me, then lowers her gaze. I keep waiting. I decide to help. Clipped:

“So you mean you don’t really care about my socks?”

She opens her mouth.

“Isn’t that what I said?”

She sighs. Uncrosses her legs, crosses her arms. Impatient:

“Yes, yes. But what I really mean is that today I don’t feel like wasting. Not wasting, spending. Don’t be offended. What happened is that . . . I’m not willing to spend . . . I—I bet on the plums.”

Confused, I wait. She takes a cigarette out of her purse, searches in her bag, looking for a light. I hold out my nondegradable lighter, but she’s already found a matchbox. She lights it, shakes the flame in the air. Confident:

“Listen, today I’m not willing to spend forty-five minutes discussing the sub- or un-conscious reasons why I said you’re wearing mismatched socks, all right?”

I tap my cigarette against the lip of the ashtray.

“Something happened today.”

I uncross my legs.

“Something very important.”

I look at the clock. Fifteen minutes have gone by. I look at her again, waiting for her to talk. She doesn’t, but keeps staring at me, her cheeks flushed, her eyes shining, as if she’s sick with a fever. I wait a while longer. Now with my legs uncrossed, all I have to do is stretch them out to expose the color of the socks. I’m so curious about them, I move my leg forward just a tiny bit. Maybe the burgundy one with the white edge and the black and red plaid one. Ashes from my cigarette fall on my pants again, but a light shake is enough to make them fall off and onto the carpet. This time, I don’t even need to wet my fingers to try to take them to the ashtray. When I look at her again her eyes are shining so much I decide to try to help her again. Calm:

“What is this very important thing that happened to you?”

She lowers her head, mumbles something, in a voice so soft I can’t hear a single word.

“What was that?”

She puts out her cigarette. Anxious:

“On my way here I stumbled into a coffin. With a corpse.”

If I move one of my legs very slowly to the right side of the chair and bend it at the knee, I can see the color of at least one of the socks. But she continues:

“When I turned the corner, a funeral procession was coming out of that big yellow house down the street.” She takes another cigarette out of her bag. “No, that’s not how it went. Before that I’d bought a kilo of plums.” She holds two cigarettes in her hands for a moment, one lit and one not. Then she lights one with the other. “No, that’s not how it went either. Before that, yesterday. I slept until three o’clock this afternoon. Then my mother asked me to come here.”

She stops talking, makes a face. I don’t know why, until she puts out the cigarette. She had lit the filter.

“Shit.”

She’s never said a bad word before, I think.

“Listen.”

Maybe it’s the green one, with gray diamond shapes. Along with the gray one with red details.

“I was on my way here. I was on my way and feeling dizzy, like I always do when I sleep too much. And I don’t even sleep, it just feels like I do. It was on one of those fruit stands that I saw them. I was walking with my head down, but . . . Such red plums. I was thinking about a lot of things when—”

“What things?”

“What things, what?”

“The ones you were thinking about.”

She lights another cigarette. The right end, this time.

“I don’t know, the things I’ve been. Very sad, or . . . Shitty, all of it. But that doesn’t matter, please. Don’t interrupt me right now. There’s something inside me that keeps sleeping after I wake up, very distant. It was a long time ago.” She takes a deep drag. And releases, almost forgetting to breathe. “That’s when I saw the plums and they were so beautiful and so red that I asked for a kilo of them and that was the last of my money, you know, so I thought if I buy these plums I’ll have to walk home but who cares that I’ll have to walk home, might even loosen me up a little so I was eating the plums slowly, couldn’t stop eating them, I’d already eaten about six of them when I turned the corner down the street, a coffin was coming out of the yellow house and I think the coffin was full, I mean, there was a corpse inside it because it was coming out of the house, not going in, and that was right when I turned the corner and there was no time to dodge it so I walked right into it and dropped the plums on the sidewalk, and it was then that I noticed these people in black with sunglasses and handkerchiefs and there were a whole bunch of flower wreaths, it must have been a very rich corpse and that hearse was parked there, and only then did I understand that it was a wake. I mean, a funeral. The wake is beforehand, right?”

“Right,” I confirm. “The wake is before.”

“They all stood there, staring at me. I knelt down and started to pick up the plums from the gutter. I wasn’t worried that this was a funeral and it all had stopped because of me, you know? I picked them up one by one. Only after I’d put every single one back in the bag did things start to move again. I continued on my way here. They continued carrying the coffin to the funeral car. But first they stood there for a minute, like in a photo. Me picking up the plums and all of them staring at me. Are you listening? All of them staring at me, and me picking up the plums.”

She stops talking for a moment. Then she repeats:

“Staring at me, all of them. Me, picking up the plums.”

She puts out her cigarette. I check the clock. Fifteen more minutes to go. I light another cigarette. Touching the leather on the outside of her purse, she feels something inside it carefully. I assume she’ll take out another cigarette but she doesn’t even open the purse. Just feels this object inside it, distracted, with the tips of her fingers and bitten nails. So far away I have to bring her back.

“What are you thinking about?”

She laughs. She’s never laughed before.

“There was this silly game we played when I was a girl. At every house party, Cuba libre, you know.” She takes the object out of her purse, but keeps it in her fist. “Such a long time since I last had a drink, since I last danced. God, so long since I’ve had any fun. You think people still party like that? And Cuba libres, do people still drink them? And that game, you think people still play it?” She looks at me. I imagine the object she’s holding in her hand is a matchbox. “It was kind of a dirty game. But innocent dirty, kind of childish, I guess. You’re blindfolded, then they point at someone else and ask if you want pear, grape, or apple. Pear is a handshake. Grape, a hug. Apple, a kiss on the mouth.” She laughs again. “But we would find a way to talk to the person asking the questions and then, when they pointed at someone we have a crush on, we’d secretly take a peek. Then we’d say: apple.” While she is speaking, I notice she is softly rubbing that object against her blouse, over her breasts. She laughs again: “That was the first time I French kissed.”

Now her shoulders look too low, her back almost bent. Her eyes shine less, start to look misty. I think she’ll cry. And what else, I think of asking. She straightens her posture.

“How much time do we have left?

I look at the clock.

“Five minutes.”

“Five more minutes to go, no words anymore,” she hums with a tone that strikes me as ironic. “There’s a song like that, isn’t there? Or I just made it up, who knows.”

She continues rubbing the object against her blouse. What might it be, I think without much interest. She looks at my socks again. Maybe one entirely white, the other blue with thin black stripes.

“Look, before I leave I’d like to say that I bet on the plums. That’s what came to mind when I walked away. As I entered the building, facing away from the funeral procession, the entire time, without looking back, in the elevator, in the waiting room, as I came in and sat down here.” Her eyes shine more. She’s never looked me in the eye this much before. “I want to. I need to keep betting on the plums. I don’t know if I should. I also don’t know if I can, if it is . . . Allowed, I don’t know. I think that I also don’t know what possibility and obligation are, but I know very clearly what need is. Desire?” She interrupts herself as if I’ve asked a question. But I haven’t said anything. “Desire, we make up.”

She puts out her cigarette. And I yawn, unintentionally.

“Or not,” she says, getting up. She’s never gotten up before I say well, that’s it for today, before.

I get up too, without having planned to. This has never happened to me before. She continues rubbing the object against her blouse. Only when she interrupts that motion, her hand stretched out to me, do I realize. It’s a plum. Ripe. The color of red wine. Or blood, perhaps. She walks over to the table, places it on a book next to the phone.

“This is for you.”

“Thank you,” I say, unintentionally.

She fixes her hair with her long fingers before leaving.

“Happy New Year,” she says, on her way out the door. Her eyes glimmer.

But it’s just September, I think of saying. But only think of saying, because she’s already shut the door behind her. I open it again, but the waiting room is empty. For a moment, I stand there, listening to the sound of the clock in counterpoint to the air conditioner. Then I walk over to the table. I touch the plum. The color of blood, of wine, seems to reflect itself on the polished surface of my nails. It’s so glossy it shines: the peel almost bursting with the pressure from the stuffed pulp, which I picture as yellow, juicy, clicking against the teeth. I decide to call her parents, to advise them to have her committed again. But first I have to check the color of my socks. Maybe the lilac one with navy stitches. My glasses slide down my nose again. Or the yellow one with white stripes. There’s no time left. The next patient knocks on the door.

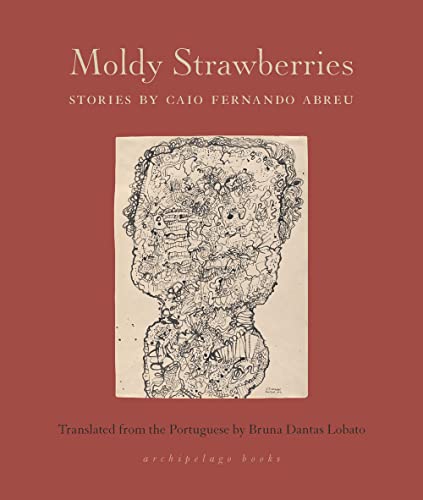

Copyright © 1982 by herdeiros de Caio Fernando Abreu. English language translation © Bruna Dantas Lobato, 2022.