“Reality is not a given: it has to be continually sought out, held—I am tempted to say salvaged,” John Berger writes in his 1983 essay “The Production of the World.” “Reality is inimical to those with power.”

There’s a Berger short story, published in the New Yorker in 2001, called “Woven, Sir” that reminds me, in a way, of this. It’s a story in which Berger’s adult narrator describes being in Madrid, waiting for a friend at the Ritz Hotel (with classic Berger observations around the sensual realities of class and wealth, as in his impression, in the hotel, of “the deafness of money . . . not an empty silence, but a silence of seclusion—like that of the depth of an ocean. . . . The seclusion, here, prompts me to remember the clamor of shanty towns and the everlasting racket in prisons”)—while also, simultaneously, recounting his own childhood memories of the outsize influence of an older man in his life: a man whose last name is Tyler, whom the adult narrator believes he is encountering, in the present, in the hotel. As a reader you’re never entirely sure if he’s truly seeing Tyler there in the lobby, in the present. Other hotel guests, too, get named after mythical figures—for isn’t that who Tyler is, for Berger’s narrator: a mythical figure?—one, Circe, another Pasipha, another Telegonus, but soon enough a reader realizes that the point isn’t to know for sure whether or not Tyler is there, in Madrid, in the present. In every way that matters, he is there, in Madrid, in the present. The narrator remembers something his mother once told him: “The dead don’t stay where they are buried. . . . You may meet the dead anywhere.”

Woven, the story is, with the past and the present, so there is no divide, grammatically or structurally, between the two time-spaces, and the reader lives them both, sometimes in the same paragraph; the narrator waiting for his friend Juan as an adult and hearing Tyler’s voice in the hotel lounge.

Tyler was the narrator’s tutor in a place called the Green Hut, “roofed with corrugated iron that was painted green. It had a door that fitted badly and three small windows. There was no heating and no water. . . . This hut on the edge of a field was our school. Nobody, however, referred to it as such, because Tyler insisted that he was not a schoolmaster but a tutor.”

It was here that Berger’s narrator says he first learned to write. We are in a primal memory, of a primal place. But soon the picture of this makeshift classroom—in which the narrator is joined by five other pupils, all “coached . . . to get into what were considered good schools,” “making it possible to pass me off as a gentleman boy”—starts to come into focus: it’s also a place where the six young children suffer from the cold, where they get chilblains and red noses; where the narrator can’t remember how or where they shat, but does remember “vomiting there once”; where they are subject to the terse, half-haughty, half-tender catechisms of an adult man whose power over the children in his care will mark the narrator’s entire life. It’s important to note that the asymmetrical dynamic between Tyler and the pupils is one defined not only by their teacher-student relation, but by the divide of class—these are not the children of the powerful, with their tickets to Eton already set in stone; Tyler’s tutelage is their ticket to class mobility. His lessons are in essence a kind of ad hoc training center for families circumventing the British schooling system—which is to say, the British class system. He teaches them “writing,” but writing according to Tyler also has everything to do with class propriety and order: “Writing involves spelling, straight lines, spacing, words leaning the right way, margins, size, legibility, keeping the nib clean, never making blots, and demonstrating on each page of the exercise book the value of good manners.” Values clean as a priest’s.

“You never stop being interested, that’s where the trouble begins,” Tyler scolds Berger’s narrator, sounding like every white teacher I ever had growing up, before gruffly ordering the child to wrap the end of Tyler’s scarf around himself to keep warm and keep quiet. Most of Berger’s narrator’s recollections of Tyler consist of the older man dressing him down for some fault or another, with the dressing-down its own form of gruff affection: his inability to pronounce Spanish properly, his inability to saw straight, his inability to spell. Berger’s narrator says both he and Tyler knew “the hopelessness of the project”—getting the boy to one day pass for a gentleman—“and this was our secret, which made us, in a strange way, accomplices.” Treated (as some adults do treat children) as if he is older than his years, Berger’s narrator remembers, during a very cold winter, mending the adult Tyler’s glasses with sticking plaster: “I was seven years old,” he says simply. (In Here Is Where We Meet, published four years after “Woven, Sir,” the short story appears again, slightly revised, this time under the title “Madrid”—and this time, the child-narrator says, “I was six years old.”)

And when Berger’s child-narrator lingers after class in Tyler’s private rented rooms (“from where later I caught the bus to mine”), intimate enough to be looking at a photo by the older man’s bedside, the child thinks: “Nobody can help him, I told myself, as I sat in the wicker chair before his gas fire, rubbing my chilblains and eating my toast and honey. He’s too old and he has too many hairs growing out of his body.”

Secrets and complicity; hopelessness and tenderness; an adult’s body and a child’s memory. Here is a grievous portrait, grievous most of all in its unforgetting attention; grievous most of all in its kindness. This is what a formative influence is, after all: to be influenced. To be formed.

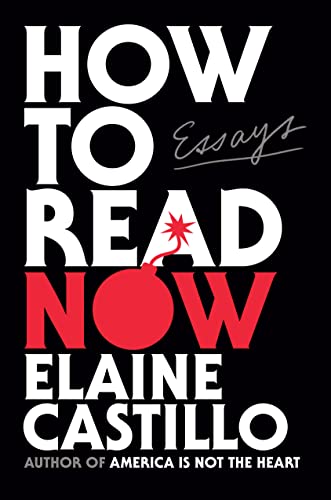

From How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the author.