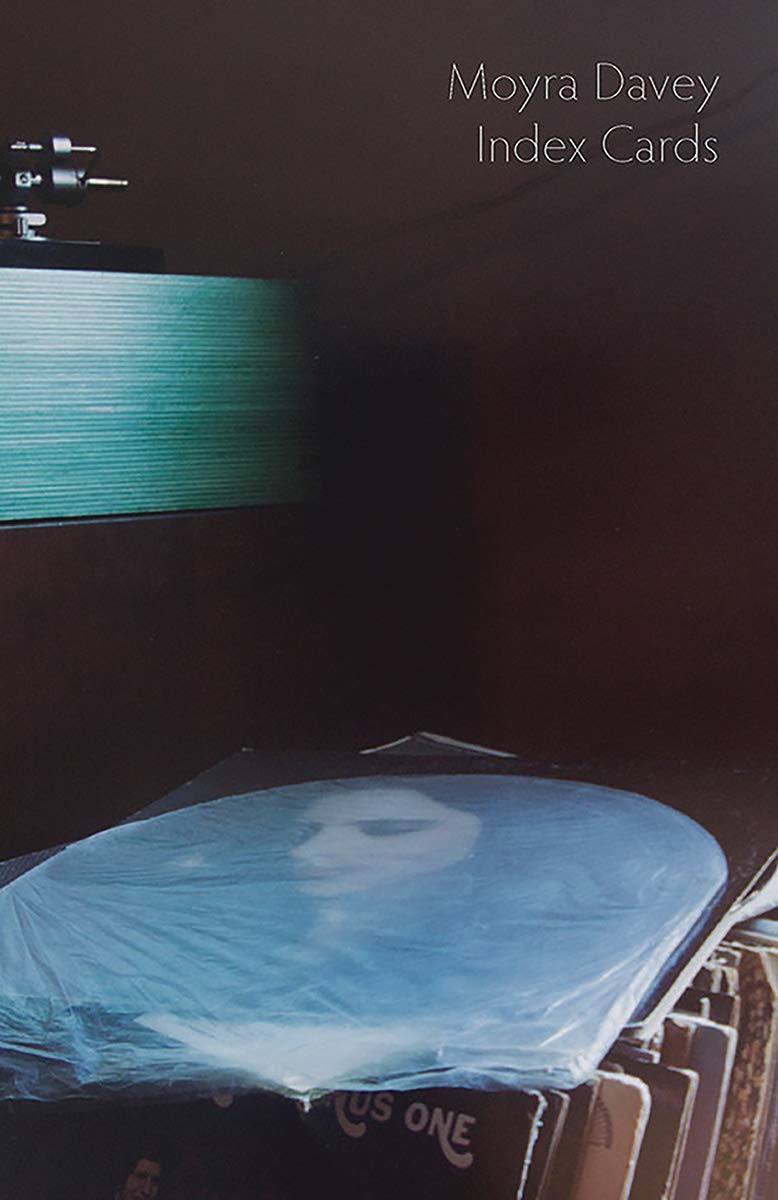

Moyra Davey began her career in photography and filmmaking. Her experimental, cross-media artworks incorporate elements of fiction, documentary, and journals. Writing has long been an important aspect of Davey’s visual work. In her recent collection, Index Cards, she lingers on the page, creating an associative personal canon through close readings of literature, theory, film, her own journals, and more. Throughout, Davey returns to the same themes and vignettes: Walter Benjamin’s epistolary account of a clock seen from his study, for example, or the unconventional lives of eighteenth-century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughters. With each telling, these stories shift slightly: a document of memories rewriting themselves, as circling becomes a way of moving forward.

I spoke with Davey via Zoom about creating during quarantine, writing about writing, and finding yourself in the frame.

What appeals to you about biographical and autobiographical writing?

I’m one of those people who has always read biographies, from the time I was a teenager. I love the form. That’s how I came to Mary Wollstonecraft, by reading about her life, and via the letters she wrote when traveling through Scandinavia. I tapped into her life, and Mary Shelley’s, and I started to make connections. I realized that important dates from their lives occurred more or less two hundred years before events in my own family life. That realization enabled my own writing; it became a way to connect personal stories with other literary histories and a feminist history of social justice. It’s not easy to write about yourself; I have the impulse, but I need permission, and I find it through connecting to other lives.

In “Les Goddesses” and “Caryatids and Promiscuity,” I used the device of events in our respective families falling on the same dates two centuries apart to connect my sisters to the Wollstonecrafts. Mary Shelley and her half-sister and her stepsister were among the few women of the time who were very well educated. They hated the conventions of their lives and being oppressed because of their gender and they rebelled against that as much as they could, which reminded me of my defiant, nonconformist sisters.

In “Opposite of Low-Hanging Fruit,” you write about your return to portraiture after abandoning the form in 1985. Why did you renounce portraiture, and how did writing lead you back to it?

When I was at the Whitney Independent Study Program in the 1980s and ’90s, I was immersed in reading critics like Laura Mulvey, Martha Rosler, John Berger, and Victor Burgin. I was very influenced by their critiques of representation and, in particular, representations of women. So, for a number of years, I decided that I wasn’t going to make portraits anymore and I started to move toward other media.

Though I always kept journals, I didn’t write until I wrote the introduction to Mother Reader, an anthology I edited in 2001. Immersing myself in that literature of maternal ambivalence gave me the urge to start writing, and that development happened in tandem with wanting to leave photography completely for a while and only work with the moving image. I started to combine writing with video, and I used myself to deliver the texts that I had written—without even thinking about it, I put myself, a woman, in the picture. Slowly, it dawned on me that through writing and filmmaking I had naturally moved away from this prohibition.

You often write about the process of writing: about scavenging for materials, misremembering anecdotes, or editors’ comments on your work. What does your process look like?

I’ve always loved to read writers writing about writing. I find it fascinating and started to do it myself. You could say it’s another device for overcoming blockages and making transitions. But I’m not consciously thinking about that when I write; it happens naturally. I sometimes use journals and notebooks as source texts; I’ll fold in a fragment from the journal.

When I’m writing an essay, I hardly write in my journal—the “writing drive” gets diverted and all the energy flows into the essay. The journals and notebooks are important and vital but they are also a concrete representation of the accretion of time, and the fact of aging, and that can generate a feeling of unease. At times, a particular journal, if it contains too many laments, will begin to feel distasteful and burdensome (I wrote an essay for Cabinet in which I compared a certain journal to a snot rag). The East German writer Christa Wolf had a great model: she kept a journal in which she wrote one entry on the same day every year for fifty years. I like the restraint and economy of it. Also, William Godwin and his circle would record notes every day, but the writing was minimal and coded—ellipses to indicate sex, a time of day to record a death, a little sun symbol used ironically by Mary Shelley to indicate the presence of her rival on a given day.

But I don’t know where I’m at with the journal right now, to be honest. I’m trying to recalibrate with everything that has transpired and continues to develop.

How are you staying focused during the pandemic?

A friend in Montreal sent me this incredible short essay by the French philosopher Catherine Malabou. She was stranded in Irvine, California and wrote about Rousseau’s confinement during a plague, as well as her own confinement. She talks about how Rousseau had a choice between quarantining with others on a boat or quarantining alone in less than ideal conditions. He elected to be confined to a hospital by himself, with nothing but his trunk and clothing. So, he made a bed out of his jacket and turned his trunk into a writing desk, transforming his isolation and meager means into an opportunity to wholly dedicate himself to writing. Malabou writes that Rousseau found a way “to isolate from collective isolation, to create an island (insula) within isolation.” She says that she had to do something similar—to find confinement within her confinement, a sense of solitude within her isolation. Establishing that freed her up to write.

Following on Malabou, I cleared my desk of ancient clutter and dust, and useless papers I’d let pile up. That helped, but still, it took months for the dazed feeling to lift, and for me to feel that a piece of writing I’d begun a year and half ago was still relevant, and that I could continue working on it.

Cassie Packard is a writer, editor, and researcher based in New York.