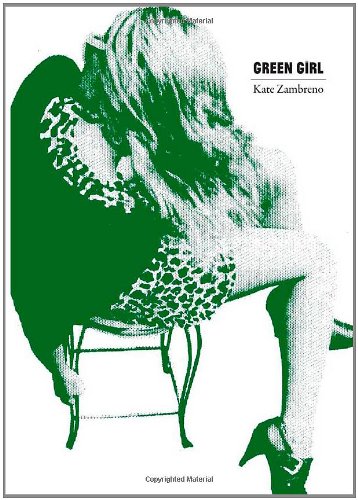

Kate Zambreno is the author of the novels O Fallen Angel and Green Girl and of the forthcoming memoir-slash literary investigation of the overlooked women of Modernism, Heroines. She also finds time to write the excellent blog, Frances Farmer Is My Sister. Green Girl revolves around Ruth, a young American girl who’s working as a temp at a London department store (which she always refers to as Horrid’s). Ruth is kind of aimless; we don’t know a lot about the substance of her life. We know that her mother is dead and she isn’t in regular contact with her father. She doesn’t have any real friends in London, nobody that she’s taken as a confidante. It’s as if she’s roamed off beyond the reaches of her regular psychological support network, the relationships and responsibilities that remind you that you’re a person, and found herself at a loss as to how to stake out an identity in this foreign place. She has a lot of bad sex and lives with this roommate who isn’t nice to her, and Ruth isn’t particularly nice back. (Their passive-aggressive, ambivalently competitive dynamic sort of reminds me of that between the twin protagonists of Czech New Wave director Věra Chytilová’s film Daisies.) Ruth as a character is often frustrating — perhaps because her youth and aimless naïveté sends us twinges of shameful recognition of, as Joan Didion once put it, “the people we used to be” —but I found Green Girl utterly captivating. I started off by asking Kate why she decided to make her novel about a character who could easily be written off by the reader.

Bookforum: Ruth doesn’t really have a strong sense of her own personal needs. She’s not really politically engaged, and the media she consumes is movies and celebrity magazines—

Kate Zambreno: And fashion! She loves fashion.

Bookforum: Yeah, and fashion! That’s like a staging ground for her own sense of fantasy. Ruth is not stupid, but she is inarticulate, and she lives this very external life: it’s hard to even get a sense of what she feels about herself. She’s the kind of person who, at the moments when you identify with her in the story, it’s sort of an uncomfortable experience. And I think that’s a hard thing to do—to center a story around a character who can be really unlikable. I sense that you’re making a point about the range of female experience, and the kinds of female experiences that are most often told in literature, and the kinds of female experiences that fall outside that boundary. So I’m curious what you think of that line: the literary versus the non-literary, let’s call it, and why it is that you decided to tell the story revolving around such a seemingly difficult character.

Zambreno: It’s a good question. I wrote Green Girl a while ago, and there’s not even Tumblr or Facebook in Green Girl, and obviously identity-forming is totally different now, because so much of it is done in public, on the Internet. I think that when I started Green Girl, I was really interested in writing about the toxic girls I had been, and had lived with, and known. And where does that toxicity come from? It comes from the culture, it comes from our training, our sort of poisonous training. But I do think that I love Ruth—I love Ruth a lot. I’m very frustrated with her, and I am often very annoyed with her, but I was maybe satirizing or conjuring up a former self, and through the process of writing the novel, it became not my current self any longer. I mean, I’m obviously not Ruth, not like a Jean Seberg gamine blonde.

Bookforum: You do have short hair.

Zambreno: I do! So there’s certainly some autobiographical stuff taken from it; my experiences are often there—or my observed experiences. But you know, I’m 34 now, and so that’s why the narrator character started to develop in Green Girl, this narrator who’s very integral to the book, and very conscious that this is a novel—and that Ruth is a character. I mean Ruth is a character in so many ways. She’s very literally the character in my novel, but she’s also the character in so many other novels, so she hasn’t really become her own author or subject. I was reading Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex, and Simone de Beauvoir—or Simone de B, as I call her in Heroines—is really hard on the young girl. She just thinks she’s totally silly, and has no sense of self at all, and I just think it’s probably a bit foggier and fuzzier than that. And certainly there are a lot of women Ruth’s age who are extremely self-aware and articulate. I was not one of them, nor were my friends. [Laughs] But I think that eventually, the novel did turn into a commentary about ingénues in literature. The epigraphs in the book are kind of an Arcades Project of the young girl, the quote from Walter Benjamin’s work on the flâneur. And Ruth is kind of a flâneuse—she’s wandering around, kind of a cipher. I think you’re right: She’s not stupid, she’s not entirely smart either. But she has something. But I don’t think I wrote a novel about a dumb girl. I wrote a novel about a very bright person who’s probably defined by the fact that she watches things. So to me, that sense of watchfulness makes me think that she will gain a sort of consciousness soon. Ruth’s struggle, which I found really interesting—and this what I return to a lot—is she’s not really trying to be empowered. I think our feminist conversation now is about empowerment. And she’s often looking for the absence of that, to sort of be destroyed. The sex stuff is part of that, and her obsession with mysticism and death. She’s almost looking to be lost. I think that’s why some people have found the book a bit frustrating. In some ways it’s very feminist—I mean obviously, I’m saying I’m inspired by Simone de Beauvoir’s young girl—and I’m obviously looking at a girl’s subjectivity, and what makes her come into consciousness, but I don’t end with her coming into any sort of consciousness. So it’s an open text.

Bookforum: Yeah, that’s interesting—the fact that for women of Ruth’s age, with feminism having existed as a political movement now for as long as it has, there is a wider range of choices available, and perhaps it’s almost thanks to feminism that Ruth can choose to be aimless.

Zambreno: Yes! But I think she’s quite alienated.

Bookforum: Yeah. I don’t think she’d put it in that political context.

Zambreno: No, she’s very apolitical. I was living in London when I was writing Green Girl, and I was married. I was a young married person and working in a bookshop, and I was very struck by the sense of being a foreigner in a big city, and that experience, which then I also linked to the experience of being a young woman—even then, I was probably 25 when I started writing it—and feeling extremely looked at. It’s like John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, where he says that the woman is always aware of being looked at. And so I was interested in how that, in some ways, makes us too aware, and how that changes a coming to consciousness, if you’re always aware of others watching you and you’re kind of an actress.

Bookforum: Yeah, it’s true, Ruth does feel like an actress in her own life. And it’s true she has that double layer of scrutiny she has the otherness of being foreign, and the otherness of being female.

# # #

Bookforum: I think that to see a book like this through a feminist lens—not to imply that there’s only one feminist lens—presents some challenges, because I do want to read literature that explores women’s perspectives, but I also want, on some level, literature that doesn’t make out women to be total fuckups.

Zambreno: Right.

Bookforum: And maybe that is closed-minded. Perhaps bringing that political dimension to it, that concern about “letting the side down”—that’s why political platforms shouldn’t necessarily get to be the aesthetic judge of literature.

Zambreno: I teach feminism, I teach women and gender studies, I view myself as a pretty radical feminist in my personal life—but you know, in college, I was a complete screw-up: on various psychotropics, sleeping with horrible boys while also taking feminism and philosophy courses, friends of mine being institutionalized while also very much identifying as being feminist. We’re in this weird post-feminist time. There is this character of the ambivalent libertine, who isn’t quite a libertine . . . even Sasha Grey is not a libertine. She might say she is a libertine, and she’s fascinating— her love of Godard films, her love of Nietzsche—but there’s this really ambiguous femininity happening now, which is both extremely aware and not entirely in control.

Bookforum: And of course it’s all taking place in a social context that includes some of the most horribly polluted visual culture, with particular regard to young women and their bodies, and the commodification of their desires.

Zambreno: It’s crazy, and it’s all in public. Identity is formed almost entirely in public right now. I mean, I’m not of the school of thought that—all of my writer friends are like either six years younger than me, or like six years older, and there’s such a divide in terms of notions of identity and femininity—but I’m not someone who thinks, oh, you can’t be a writer and be of the Internet generation. It’s just that it is so difficult navigating being a woman, or being a girl, and being a writer now.

Bookforum: The way that Ruth frequently sees herself through the eyes of others sort of reminded of some things you’ve written on your blog about the alienation from self of writers who engage in journalism, and that sort of objective, third-person voice. In your manifesto post, you specifically mention the writing of Dodie Bellamy and sort of joined her in calling for writing that is more willing to at least acknowledge its authorial conflicts and point of view, and maybe to be more complicated—more vomitous, to use your word. Is that crazy, or is there a connection between Ruth’s alienation, and your alienation—that, I take it, you sometimes feel as a writer, or have felt as writer of journalism?

Zambreno: I’ve always been really interested in the woman writer—I think that’s my main obsession. In some ways, Green Girl isn’t the best example of that. But in some ways, Green Girl is a novel about a girl who’s not yet a writer. And in terms of being a “writer,” I mean that she can be her own author, can attain her own subjectivity. I’m really interested in the mirroring of being a public writer with being a public woman, like all these female actresses that have historically had breakdowns or have felt really alienated: Clara Bow, Marilyn Monroe, of course the great Britney Spears. I think there is a link there in terms of being alienated, in terms of your interior self versus your exterior self. There is a level of performance to being a writer. I write about Elizabeth Hardwick in Heroines, who is a brilliant critic. She was married to Robert Lowell, and her book Seduction and Betrayal is about all these female characters and female writers: Zelda Fitzgerald, Sylvia Plath, Ibsen’s women. And it’s really interesting because she writes this book about these famous wives after Robert Lowell leaves her for the writer and muse Lady Carolyn Blackwood. There’s none of her self in it, but it’s everywhere. I can’t figure out if that book is a tacit act of revenge or a complete hiding of the self. To me, my criticism comes out of tremendous feeling; so, it’s hard for me to be objective. Which I think means I’m probably not the best rhetorician, but I make up for it with really intense feelings.

# # #

Bookforum: Speaking of literary disciplines, or modes that are sometimes helpful but that can also pose certain challenges for the concentration needed to tackle longer forms, what about blogging?

Zambreno: I started blogging when I was living in Akron, Ohio, where my partner was a rare-books librarian. All of “Part One” of Heroines is actually set in Akron. And knowing no women writers, or writers at all—when I was journalist, I covered the literary scene in Chicago, but I wasn’t really a part of it—I was just communing with these mad wives of modernism, and starting to form this other community, so it was this really pure, beautiful thing for me. Blogging has gotten really complicated. I think that suiciding your blog, if you have a personal blog and you’re a writer, has become almost a cliché of the form. [Laughs] It’s like, trying to quit it, talking about quitting it, wondering what it is. I end Heroines by talking in detail about blogs, how they’re these interesting notebooks that are unfinished—especially just the community of bloggers that I read, who are mostly women—and it’s hard to know what to make of them. I feel we are participating in a culture, and perhaps forming some sort of counter-culture. Something on the margins. But it takes up so much of your time. And much like a journalist, now I’m writing for this immediate consumption; part of my awakening a while ago was about how that wasn’t good. Writing a book, you kind of have to be in this world for a while.

Bookforum: Yeah, the immediate feedback that blogging offers is strangely addicting. I worry sometimes that those of us who write on the Internet are training ourselves to always be looking for that cookie, that comment, that first comment that goes up minutes after the post goes live.

Zambreno: Which is why I quit journalism. It’s because I was always looking for that cookie. I wrote a kind of proto-blog, a column for Newcity under the pseudonym Janey Smith, after Kathy Acker, that I called “Fresh Hell,” after Dorothy Parker. Very pseudo-autobiographical, and I always got so many comments and emails. And I craved that. But I think you want to start writing something more complex. But then blogging’s brilliant. I don’t know, maybe people only read the Internet. I mean, we’re in a post-book culture.

Bookforum: [Laughs] Don’t say that!

Zambreno: It’s the one thing you can write that you know people will read.

Bookforum: It’s true, it’s true . . . It’s a little bit crazy that we live in this world where metrics and your audience are so minutely traceable and trackable, and the feedback is so intense and immediate. So yeah, things that only happen on the Internet can have as much cultural impact as “real” things.

Zambreno: So I feel in some ways very divided by it. Especially with women, and young women—there’s such community building on the Internet.

Bookforum: Yeah. The Internet of course has huge potential to be a space for groups that are marginalized in traditional settings—well, in public life, in literary culture, and in the establishment—to congregate, and to make their own news, tell their own stories. Maybe that’s a naïve view of the Internet, but I do still think that kind of culture is possible, and it cheers me every time I see a site like that, with a community forming around.

Zambreno: The web is a toxic space that then can also be a very safe space, so it’s hard to mediate that.

Bookforum: Definitely. Speaking of women writers and community, you’ve written about other women writers that you’ve discovered and felt an immediate affinity and identification with—people like Dodie Bellamy, Kathy Acker, Eileen Myles. And I guess what these people and what you among them have in common as a group is clearly privileging the female experience, and especially concentrating on telling stories of female experience that are less authorized by mainstream publishing.

Zambreno: Less glossy. I think that those writers you named—who of course I admire—those three women are sort of classified as New Narrative writers, so I would say they are my fore-mothers, them and Chris Kraus—they often write about an abject subjectivity, or being in this more powerless position, they write about the body, the very messy body, the undisciplined body. So yeah, it’s certainly . . . not always likable characters.

Bookforum: Yeah, those are all late-twentieth-century writers. But is there a vein in women’s writing, is there a longer tradition of this? Clearly you have a profound engagement with many of the women in the modernist movement.

Zambreno: Yes.

Bookforum: But is there some secret overlooked history of messy women writers that we just aren’t taught about and forget all too easily?

Zambreno: Yes. And then I think what is most interesting: Heroines was actually a novel called Mad Wife. And then I was writing these blog posts, trying to figure out this novel, and then Chris Kraus approached me and said, you should write essays about these modernist women. I didn’t know that Chris Kraus was obsessed with Jane Bowles and all these women. So there was this notion of, these women should be written about in some way. But what I find really interesting is, yes, there are the women who are considered more minor like Djuna Barnes, who was a journalist, or Jane Bowles, or Jean Rhys, certainly Anaïs Nin. And you know, there are a lot of people who just hated, hated, and hate Anaïs Nin, which I always . . . I think the disgust for girls with their LiveJournals is a disgust for Anaïs Nin. Like I feel like there’s a link there that’s very contemporary. There are the women who wrote, but what I find most fascinating about modernism is the women who seemed completely charismatic, and completely like artists, but did not write, or whose writing does not really exist. And so what kept these muses from writing? And something I ask in Heroines is would they have blogged? Would they have Tumblred? An example would be Laure. She was named posthumously Laure, but she was Bataille’s mistress, Colette Peignot, who was a really interesting political figure and writer. And all that remains is just a small collection of fragments of her writing that City Lights put out, because Kathy Acker was obsessed with Laure. So there are traces. And I think part of the feminist project is reclaiming these writers. I think of all the surrealist women written about who didn’t write their own books like my milk-carton heroines. Like, where were you? What was your life, really?