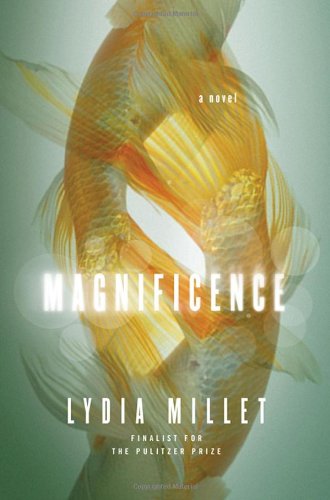

Writing in Bookforum last year, Minna Proctor said of Lydia Millet’s fiction that it “takes aim at the metaphysical jugular.” Over the course of eleven books (including two for young adults) Millet has won the respect of readers and critics for creating “exquisitely flawed characters” and pushing them “beyond themselves, their experience, their expectations” towards powerful transformations. Though she’s been shortlisted for a Pulitzer and awarded a PEN prize, Millet is not just an acclaimed novelist and short story writer; she is also a passionate environmentalist. The five years she spent completing her recent trilogy of novels—How the Dead Dream, Ghost Lights, and the recently published Magnificence—did little to interfere with her work as a staff writer for the Center for Biological Diversity, or her continued dedication to younger readers. The Shimmers of the Night, the second installment in a series that she began last year with The Fires Beneath the Sea, was published in September. Bookforum recently spoke with Lydia Millet about her various projects.

Bookforum: Your new book, Magnificence, ends the trilogy of novels you began with How the Dead Dream (2008). For how long were you at work on this project?

Lydia Millet: It took me about five years.

Bookforum: Did you set out knowing you were embarking on a larger artistic project, or did it take on a life of its own, so to speak?

Lydia Millet: I knew it would be three books and I knew something about the people in the books; I knew the stories would revolve around the crisis of extinction, at varying distances from it. Going away from it and returning. I had to write about that, not only because it’s something I work on every day—I’m an editor and writer at a group called the Center for Biological Diversity, where I’ve been now for more than a decade—but because it’s one of the great tragedies of our time and of course of capitalism. It’s hard to write about and hard to read about, though, one reason I hadn’t tackled it before. But finally I wanted to take on that hardness fairly directly.

Bookforum: Magnificence’s Susan Lindley, like T. in How the Dead Dream, is undergoing a transformation as the result of the death of a loved one. Would it be fair to say that one of the trilogy’s overarching themes is loss?

Lydia Millet: Yes. I wanted to make a bridge between the loss of individuals and the loss of whole species. Fiction constantly deals with personal and individual loss, but very often it stops there. It doesn’t look at the massive, often more-abstract-seeming loss we’re facing during the world’s sixth mass extinction crisis. Which is not merely a biological loss but also a crisis of culture. Cultures and languages are going extinct right along with animals and plants, in a parallel process driven by the same forces. It’s dangerous terrain for literary writers because you want to avoid the kind of polemic it’s easy to fall into about these matters. I tried to take on the terrible weight of extinction in a less than evasive, more than allusive way, and in a way that was personal as well as social and political.

Bookforum: But isn’t it in the nature of cultures, not to go extinct, but to disappear or change or metamorphose? Cultures seem to me a much less tangible thing than a biological species.

Lydia Millet: Except insofar as language is a crucial component of any culture. And languages are going extinct at a breakneck pace. We’re seeing a mass homogenization of culture right now through the loss of languages around the world, as smaller, more traditional cultures are subsumed by dominant cultures and the last speakers of native languages die off.

Bookforum: I’m curious about the role of animals in your work. It’s something you don’t often encounter among contemporary writers—it’s there in a lot of J.M. Coetzee’s work, but I’m struggling to think of other examples—and yet it has a long history in literature, certainly in American literature. What is the significance of animals to your work?

Lydia Millet: We lose the subject of animals when we move out of childhood. In childhood animals are all around us, and then we throw them out. In childhood they’re everywhere, the stuff of our stories and our art and our songs, of our clothes and blankets, of toys and games. Then in adulthood they’re distant symbols or objects. They’re rudely ejected from our domain. They’re frivolous or infantile, suddenly. They’re what we eat or maybe pets. Sometimes they’re what we kill. But this makes no sense. This impoverishes our imaginations. When we turn away from animals as though they’re only childish things, we make our world colder and more narrow. We rob ourselves of beauty and understanding. We rob ourselves of the capacity for empathy. My books are about empathy more than anything else, the idea that you don’t have to be something to love it. The idea that we can love otherness, that we need to love otherness to know ourselves.

Bookforum: Do you find that fiction-writing can dramatize those issues of empathy, to engage our moral imaginations, better than other forms of art?

Lydia Millet: More directly and more overtly than other forms of art, though I wouldn’t say better per se. The interiority of fiction, the subjectivity of it, can communicate the process of empathy, I think, in a way that say painting or music can’t — through linear thought-narratives rather than emotional abstracts, but linear processes that are suffused with emotion. I’d say music, for instance, often has more raw emotional power than fiction, but what fiction has is a concrete and referential specificity, a way of relating emotion to thought that more abstract forms don’t necessarily provide.

Bookforum: You mentioned before that you work for the Center for Biological Diversity. What is the nature of your work there?

Lydia Millet: I’m an editor and writer at the Center. So I use most of my workday to edit press releases, op-eds, pages for the website, all kinds of documents that go out from us to the public. We talk a lot to the media, and I oversee, to a certain degree, the language side of our output, along with others on our communications staff. Our work is about preventing species extinction and curbing global warming, and we do science and litigation to that effect.

Bookforum: Do you find that it informs your fiction-writing?

Lydia Millet: It has to, because I spend so much time and energy on it. But it’s a chicken-or-egg question: I pursued the job because protecting animals and wilderness is a longstanding interest. I never did an MFA in writing; instead I did a master’s program in environmental policy and economics, back in 1996, and I’ve been working in the field ever since.

Bookforum: Let me invert the question: do you ever feel conflicted about these two very different activities?

Lydia Millet: Only in a practical sense, the fact that my job doesn’t leave me enough time to write — I have to snatch a half-hour here, an hour there, often at the expense of lunch. But all my efforts are directed toward a unified purpose, I think — broadly speaking to love the world and keep it close while we’re also tormented by it.

Bookforum: You’ve also just published The Shimmers in the Night, your second book for younger readers. Where does that fit in with everything else you’re doing?

Lydia Millet: Thank you for noticing! My children’s books don’t get much attention. I’m writing them for my own kids and for all kids who love to read — for the sake of their idealism and their imaginations. For the same reason I write for anyone, more or less. The series that began last year with The Fires Beneath the Sea, of which The Shimmers in the Night is the second installment, is about a family on Cape Cod with a mother who’s disappeared. The children go looking for her and get caught up in helping to fight a secret war.

Bookforum: What are you working on next? Or, to put it differently, what would you like to be working on in the future?

Lydia Millet: I’m working now mostly on the role of fundamentalism in current U.S. culture and writing two books at the same time, one that’s a satire and another that isn’t a satire at all and has to do with religion and politics and language. I go back and forth between them according to my mood. It’s a bit of a balancing act.