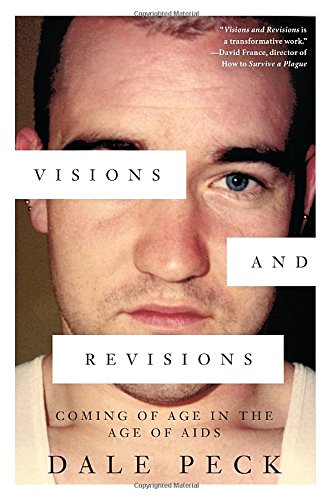

Dale Peck is not known for understatement. His reviews, collected under the title Hatchet Jobs, earned him a reputation as one of the most scathing critics of his generation’s revered literary voices. Peck’s 1993 debut novel, Martin and John, was released as Fucking Martin in the UK. His 2009 YA book, Sprout, went on to earn him the Lambda Award for LGBT Young Adult Literature and was a finalist for the Stonewall Book Award. His forthcoming work of nonfiction, Visions and Revisions: Coming of Age in the Age of AIDS, recently landed on my doorstep as an advance review copy. Interested in the title, as I too was at work on a book that is in part about the early ’90s, I devoured Peck’s memoir in two sittings. How could anyone, I thought, write a book that seemed such an unapologetic and deeply pleasurable blend of Kathy Acker and Theodor Adorno? The book’s mélange of theory and anecdote was bracing. Recently, Peck and I sat down to talk about illness as metaphor, the mediatization of AIDS in the era of ’90s talk shows, Jeffrey Dahmer, and much more.

I’m interested in the phrase you use to describe the period in which Visions and Revisions is set. I was wondering if you could talk about the specificity of it, “the second half of the first half of he AIDS epidemic”?

Well, I came up with the title a while ago—in college. I thought, “One day I want to live so long that I can publish a collection of essays or stories called Visions and Revisions. I was obsessed with this idea of a retrospective. “The second half of the first half of the AIDS epidemic” came to me when I was looking at the material I had. Sixty to seventy percent of it had been written at about that time. 1987 was the year ACT UP was founded. I was very aware of it when I was in college in New Jersey and I was the head of the campus gay group. I invited ACT UP to campus in ’88. And then I moved to the city in ’89, after I graduated, and a million things happened, between all the various things ACT UP did and being a young guy in the city and writing and selling my first book.

Then, in ’96, everything changed. Psychologically, especially, but physically—or medically—as well. The first half of the epidemic was ’81 to ’96. Those years were marked by fear and despair—a lot of anger and fighting back, but there was no real sense that fighting was going to get us anywhere. Whereas from ’97 to when I started working on this book in 2013, people fought less, but were optimistic. I think the fighting was more specific—it was done much more on a medical front.

When I think of that time, I think of Sontag. AIDS was talked about by the media in the ’90s in this newly metaphoric register. The first time I heard about AIDS was hearing that Ryan White had it, and then shortly thereafter I heard that Magic Johnson had HIV. As someone who came of age in the early ’90s, my understanding of AIDS was filtered through this celebrity, heteronormative media-sphere. Do you remember the first time you heard the word “AIDS” or “HIV”? Did you encounter it in this metaphoric sense?

I remember the first time it ever made an impression on me. It was in a high school science class, and the teacher was talking about AIDS. I actually don’t think it was homophobic, per se, but he sort of made this joke that you had nothing to worry about if you weren’t a drug addict or a man who was having sex with men. At the time, I didn’t think I was gay, because I didn’t really know what that meant. But I knew that I was sexually attracted to other boys. So, on some subconscious level, I clearly understood what it meant. And I think from a very early age I had this idea that AIDS was my destiny.

I think that’s how it was taught during that period. AIDS was my first introduction to that sort of Republican wave of fear that—in the aftermath of cases like Ryan White and Kimberly Bergalis—was attached by certain news outlets to everything from blood transfusions to going to the dentist. This sense of national anxiety was heightened by the coverage of the Gulf War in the background of American living rooms, on the evening news. There was a palpable anxiety about Gulf War Syndrome and PTSD, which themselves were so vaguely described at the time, the media almost seemed to render them more metaphor than illness. It was the first time I was aware of this idea of mortality that we’d come up against, and that culturally we were talking about it in a way we hadn’t seen before.

Yes. Because it took me so long to come out—I spent so much time denying it to other people more than to myself—I didn’t know how to shape an identity around being gay. Being a nerdy, eggheady guy, my approach was, of course, to read a lot of books and articles. I started reading gay stuff in the early ’80s, when there was a wave of late-’70s, early-’80s literature, which was pre-AIDS. It was very hedonistic. Very celebratory. It was in your face in a bougie kind of way—as opposed to the stuff that came right after that, which was in your face in a kind of punky way. The sex in the earlier books was pornographic rather than avant-garde or transgressive in the way it was described. And so I had this sense of a kind of culture that I liked. I liked how incredibly removed it was from everything I came from in Kansas. My working-class, boring white roots and all that. And then even as I was reading that material, I knew that it was all over. And then I started reading all this stuff about AIDS, and you realize that of course HIV and gay culture of the ’70s was a perfect storm—the worst possible thing.

So, I saw a lot of that culture was gone. But luckily, since I was a bit younger, I wasn’t fully conscious of what was happening during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. By the time I was in my early twenties, there’s ACT UP and there’s a context for me to come out and join in. I wanted that old world back. And then I also wanted something new.

The old world: I think one of the things I romanticized about it was that it was deeply politically disenfranchised and had no interested in assimilation—I liked that. But, at the same time, I understood that was a romantic fantasy. There aren’t many people who actually want to live their lives skulking on the outskirts of society. It’s boring. It’s difficult. It’s fun to do in your twenties, but it’s not so fun to do when you’re middle-aged. Or when you’re poor. Or when you’re already marginalized because you’re a person of color.

There was a strong feeling—both externally imposed in conservative propaganda and also internal and idealistic—that gay culture and AIDS were going to dominate my life. It became a question of whether you were going to let that be a limiting thing. Or whether you let that be a liberating thing.

In the book you explore the place we are now, not only in terms of the discourse about AIDS, but also the discourse about journalism, narrative, and the “cult of celebrity”—what you call the idea of “victim-art” and of “ongoingness”, and how we can challenge those ideas. You say, “The producers of talk shows and human-interest segments on the evening news believe that by putting a face on the epidemic they rouse viewer sympathy—and they do, and that’s the problem.” You go on to say that HIV then becomes “that much more benign, until it starts to seem not like something that should be avoided or resisted but something that should practically be embraced, a distinction, a gift even, a badge of honor and a path to wisdom.” I thought that was such an interesting and subversive way of talking about it.

I remember early on getting into an argument with someone waxing ecstatic about this AIDS fundraiser he’d gone to where he got to hang out with Sarah Ferguson. And this was before protease inhibitors—way before anybody was talking about living with this disease. And I said, “Don’t you think it’s weird that you go to a party and get drunk on free drinks and have a good old time whooping it up with Sarah Ferguson, when it’s about AIDS?” I get it—we can’t be down in the dumps all the time. We can’t constantly be grieving. But, partying and all that? It just seemed to me to be sort of a disconnect.

And I think it was. In the sense that you’re saying and also in the sense that the ’90s—not just for AIDS, but for a lot of diseases—was the beginning of the age of a scientific revolution in medicine. But at the same time it was the beginning of MTV culture and reality television. For my generation, one of the first stories about AIDS that people remember is the depiction of Pedro on MTV’s The Real World, and his roommate Puck’s blatant homophobia. In a way, this was the beginning of our being able to talk about living with AIDS the same way we talk about living with cancer. You echo that later in the book where you talk about Kushner’s Angels In America. You say, “History had acknowledged us, but it had also passed us by, by which I mean that the cultural and political response to AIDS made gay men more American, but it didn’t make Americans more gay.” That builds on the earlier idea you mention about that sort of celebrity aspect of illness as metaphor.

You know, I think I’m being a little bit of a hard-liner with that. I think America is definitely a nicer place now than when I was young.

Really? I don’t know.

There was a lot of writing back in the ’80s about how with increased visibility also comes increasingly visible backlash. Before the ’80s, before the ’90s, gay bashing was probably happening all the time. You just didn’t hear about it because gays weren’t a group you talked about in that way. And attacking them was so OK that it wasn’t the kind of thing that would even make the news. There might be a story about an assault, but the reason why the assault took place—the reason being that one man was gay or gender non-conforming—probably wouldn’t even make the story nine times out of ten. Now we hear about these terrible things happening all the time. But I am of the opinion that, as terrible as they are, they are a symptom of the fact that we are increasingly visible. We are increasingly powerful. And this makes the people who don’t like us (whose numbers I think, actually, are shrinking) that much more threatened and liable to act out. That may be very idealistic, and no one has tried to bash me in a very long time. But I do believe that that’s what’s happening.

You take a pretty critical stance on Kushner’s play. You take issue with him presenting AIDS within the context of a “gay fantasia.” I gleaned from your comments that you felt Angels was a bit of a campy, heteronormative way of inoculating traditional American theater with the concept of homosexuality.

I really loved Angels In America. I loved it, loved it, loved it. I saw the first half, and it was a full year before the second half was performed. So, you really just had to live with it. I was deeply entertained and impressed by Kushner’s linguistic brilliance, but skeptical. And then I saw the second half, and I just thought it all came together. And then I went back and saw the whole thing, and I thought it was great as a piece of theater in the moment that it came out. What I didn’t really like was the TV show. And the problem with the TV show was that it didn’t know how to address the gap in consciousness. A decade had passed. And it was a momentous decade for gay people, for people with HIV, for Americans. So many things had happened. And the play was—in a certain way that I think really great art is—so rooted in its moment that to view it outside its moment was disorienting. But the biggest thing was that when I first saw the play, I had a crystal clear sense of my own identity as a gay man and as an American. And I didn’t have that the second time I watched it. Which made the play very disorienting for me.

Later in the book, you write about visiting the Town House, and say, “The only reason I went to the Town House, of course, was to see where Thomas Mulcahy met his killer. Like any aspiring journalist, I believed it was necessary to place the two of them in situ in order to understand them better, or at least better (read: more vividly) describe what had happened to them.” You propose that journalists and memoirists have it even harder than novelists, in the sense that they reduce people “to symbol.” You say, “Journalism and memoir entailed a certain amount of projection, but I’d never realized how much role playing is involved.”

There were no two writers more influential or important to me than Joan Didion and Janet Malcolm. They were both hugely important in the way that I conceived of writing about real people. And both of them hammer home this idea that when you write nonfiction, it is almost impossible not to fictionalize your subject, because you can’t represent all of it. When you’re writing, whatever it is you put on the page is the entirety of the character. You get it all there because that’s all that exists—what you’ve made up. But when you’re writing nonfiction you’re leaving out 99 percent of the story.

When I was working on the Jeffrey Dahmer piece, which was the first big piece I did, I remember going to Milwaukee and talking to all these people: white lesbians, black gay men, black straight people. And all of them had felt so incredibly betrayed by the way the story had been reported. Everybody said exactly the same thing, which was that the journalists got it wrong. “This was not what had happened. This was not representative. This was taking a small little thing and blowing it up and trying to make it represent the whole.” I don’t think any of them thought they were testifying to the theories of Didion and Malcolm; but I remember thinking, “I’m going to fail all these people. I’m going to get all these people angry at me. Even people who disagree with each other—they’re going to agree to the fact that they don’t like the way I represent them.”

And I guess I had an idea, as a gay man, that things I read didn’t seem to capture me. All of that surrounded me as I was going out and doing my early stories. And I’m a person who, like most people, wants to know what’s going on in the world. I want to know the real things. So it was necessary for me to try and say what was actually going on, as opposed to making a metaphor out of it in my fiction, or symbols or abstractions, or whatever the case may be. I felt incredibly uneasy about it and I don’t think I ever worked out a proper solution. I feel like the closest I came was pointing it out by saying, “I don’t buy this and I’m not going to be offended if you don’t buy it either.” Because there are ten different stories that could be written about the same person, the same incident, and so much depends on the point of view you bring to it or the amount of information you have access to.

In one of the final metaphors in the book, you talk about the first time you had sex, when your watch actually stopped. The irony being that you’d been such a fan of Frank Conroy’s Stop-Time.

That’s hysterical! I never made that connection. Obviously my subconscious did, but I didn’t.

Isn’t sex perhaps a way in which, metaphorically, all of us are trying to stop time? When you describe the moment of losing your virginity and seeing your watch stop, you say you had a distinct sense that you were engineering your own demise.

Sex is a way of stopping time and becoming dead. And the fact is that when I was a sophomore in high school, when I was first beginning to have sexual fantasies about boys, I was also absorbing this idea that sex was going to kill me. By the time I had sex, safe sex had been widely disseminated and I was aware of ACT UP. I was aware of the activist Michael Callan. I’ve always wondered about the degree to which sex is a way to annihilate time and life, not in the sense of granting immortality, but in the sense of denying death while simultaneously embracing a kind of death-like condition. I think especially in my twenties, that was how I had sex. I was very much into having sex in public. Having sex in places where I might get caught. Having sex in places where it might possibly be illegal. Having sex with lots of people. Not having sex on drugs, but that’s only because I didn’t like drugs, not because I didn’t like the idea of sex on drugs. Also, I couldn’t afford them.

You talk about sex as a way “to be a stranger to yourself.”

I wanted to call the book that, but my editor, Mark Doten, talked me out of it. The original title was Visions and Revisions, but I really like this line: “Be a stranger to yourself.”

You also discuss sex in terms of the “pleasure in being the lowest of the low.”

Yes. That’s Michael Warner. And it’s funny because I very much agree with that, but I don’t think it’s universal. I think that might be a weirdness that Michael and I agree on. He was talking specifically about gay men. And I haven’t read enough of Michael’s other writing to know how far that goes.

But I do think personality, or personhood, are kind of oppressive. You are yourself all the time. It gets so boring. It’s such a trap. I mean, even as a novelist: You get to invent so many other characters, to sort of live phantasmatically through them. Still, you turn the computer off, or you put the pen down, and there you are again. And sex is a great way not to be that. I think one of the great privileges of gay sex back then—or gay male sex, I should be more specific—was the anonymity of it. The quickness of it. You could meet somebody in a room. You could be having sex with them within five minutes. And because you didn’t know them, you could imagine their personality. They could be whomever you wanted them to be. People are familiar with that, but maybe less familiar with the idea behind Leo Bersani’s question in Homos: “Who are you when you masturbate?” The root question is, “Who are you when you’re engaged in sexual fantasy?” That’s one of those moments where we shunt ourselves aside, sometimes, to become another person, or to become a kind of non-person. To actually just become a body that’s responding to certain physical impulses. I honestly don’t think I could have sex that way anymore. Maybe that’s because I’ve been married for eight years. But at the time, I think it was what was most interesting to me about sex. And I think it’s why (at least in their own perception) gay men have such a hard time having long-term relationships. Because I think the appeal of that kind of experience—you might want to say, even, the addictive appeal—is very similar to a kind of drug high. You have a fantasy of having a relationship, but really what you have is a fantasy over the other thing. But for whatever reason, this lifestyle got boring for me around the time I turned thirty.

Which leads me to the last thing I wanted to ask you about: You say of Leo Bersani’s book that he “offered a novel and in many ways appealing strategy for a revolution to dismantle the oppressive systems of patriarchy and capital. All we had to do was fuck our lives away.” I wondered if you might talk a little about what you meant by that.

One of the very first things I read about AIDS was the Douglas Crimp anthology, and the thing in it that made the biggest impact on me was Leo Bersani’s essay, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” It was so important culturally, but I think even more so to me: The idea that you were failing as a politician, as an artist, as a person, if you did not find the idea of AIDS intolerable. Anything less that that, anything that was remotely accommodating to the idea that AIDS was now in the world and we would have to learn to live with it—in the 1980s it was just too fucking soon. In the 1980s, the only response was: “This must go away. It must not exist.” Anything that said, “We can make this a part of our lives,” was—to borrow the metaphor Bersani used—like Nazi collaboration, like silent Germans who don’t actually hate Jews, but aren’t fighting to save Jews from the Holocaust. And that really meant a lot to me.

When Bersani came out with this book, I realized he was advocating a plan that I was deeply, deeply sympathetic to. In the same way that Michael Warner says that to be gay meant to enjoy being abject; to enjoy being the lowest of the low. That we used sex to do that. And the same way that I was having anonymous sex. Fetishistic sex. All these kind of things. I had a strong affinity to this idea, but when Bersani elevated it to a political program—which he did—I thought what he was calling for was the abolishment of the state, of community, of everything else.

So that was the moment I realized that the theory and the lifestyle we’d been advocating, to some degree, was circumscribed—it had its limits. Maybe there were things that were psychologically attractive about it. Maybe there were things that were culturally powerful about it. But life is a kind of mundane affair, mostly, that requires institutions and streets and, dare I say it, policemen and doctors and hospitals. And if you’re talking about abolishing the bonds of sociality itself—which was one of Bersani’s sort of fun words—you’re talking about sitting back and watching every person with HIV die. And that, in turn, resonated with a bit of the conversation that was becoming very resonant when people were starting to talk about AIDS dying out. People were basically advocating—consciously or unconsciously—segregation. The HIVs and the HIV-nots, as Allen Barnett said.

We saw that again with Ebola and the question of immigration. Do we let people into the country or do we not, essentially.

Right. The thinking being, “We’ll let them die out over there and we’ll be fine over here.” And that idea is obviously repellent to people. And I don’t think that’s what the gay and lesbian HIV activists were consciously trying to say. I don’t think that’s what they were advocating. I don’t think Leo Bersani was hoping, “Everyone with AIDS will just die off while everyone else is just fucking in the streets.” But, to me, that’s essentially what he was advocating.

It seemed, at a certain point, that we were talking about theories of changing the world, and I thought it was at that moment that you had to say, “Well, what would this theory look like in the world?” For me it was very devastating, because I once had a utopian vision. And I think that’s partly because I was young and partly because of the circumstances under which I was young. I felt like we had kind of betrayed ourselves. Betrayed our ideas. It’s one of the reasons that I like Angels In America so much. Why, in hindsight, I kind of like it more and more, because it was arguing very strongly for gay men to hang on to whatever it was that made them unique, and, at the same time, advocating for not being marginalized. Being a part of society. Which, I think, is a distinction between the visions of Tony Kushner and of someone like Andrew Sullivan, who is very much about erasing any distinction and just sort of joining that bland capitalist blur of consumerism and cronyism and just “yes-ing” the system.