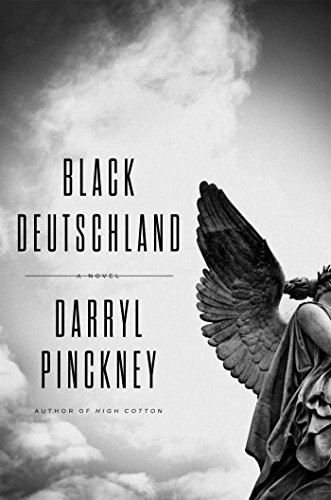

Darryl Pinckney’s second novel, Black Deutschland, is drifting and elliptical. At its center is Jed, a recovering addict from the South Side of Chicago who makes several long visits to West Berlin. It’s the 1980s, an era Pinckney portrays as blank, scattered, purged of optimism: perfect for a gay black man like Jed, who wants only to snap free of the burdens of “identity.” He falls into affairs and agonizes over the ones that work, all the while navigating an uneasy emotional détente with his cousin Cello, a failed pianist raising mixed-race children with her white, bourgeois husband.

Politics, of course, makes its brash intrusions: the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the AIDS crisis, the Reagan presidency, and the grimness on the other side of the Berlin Wall. Pinckney’s fine, erudite, allusive novel is a kind of chamber drama set against a dilapidated backdrop. Black anomie is crossed with the pleasures of the sexual underground and the dynamics of the Cold War. Love sprouts, then wilts. And the black expatriate, that melancholic figure perched on the precipice of historical change, is cut down to size, as Jed strains away from the righteous bluster of black politics toward nothing in particular.

Darryl Pinckney is a long-time contributor to the New York Review of Books, and his first novel, High Cotton, is a bildungsroman of the black bourgeoisie. It opens with a brusque, unforgettable line: “No one sat me down and told me I was a Negro.” When I met Pinckney—at his house in Harlem, which he shares with his husband, the poet James Fenton—he did sit me down, kindly, and passed me a cup of chamomile tea.

I sensed a preoccupation in the novel with how black people navigate space, especially urban space.

Jed probably shares with a number of the other black guys he meets in Berlin this sense that life in an American city has certain problems peculiar to being black in an American city, mainly police interference—which didn’t start last summer or with Ferguson. It’s been going on since the Civil War. And then the idea that Berlin is this place that nobody’s interested in. You can make up your own life. That was very much the feeling that I remember and wanted to try to evoke of Berlin in the time of the Wall: artificial in one way, but a very real haven in the other. So, yeah, they’re there to get away from various things. And have a tradition.

And yet there is an irony that in trying to leave the commitments of home, Jed still finds himself grappling with Cello, his cousin, who (though she herself is troubled by this) represents the sort of strained, intensified quality that is so characteristic of depictions of the black middle class. You use the term “clinic of the self” to describe her at one point. Yet it seems like what Jed is looking for is such a non-clinical experience.

I think in Jed’s mind, Cello is this glamorous figure who succeeded in not only getting away, but marrying into this other place. You know, where you are black is a social question. And then you’re measuring that against the way you’ve always felt inside—so, “I don’t have to worry about that here,” or, “I’m still worrying about that here, why?,” or . . . that kind of thing. But it changes from place to place, these definitions, and almost from person to person that one relates to, in a place where everyone is there to make him- or herself up. Americans in Berlin at that time knew they were in Berlin. They weren’t in Paris and they weren’t in London, they were in Berlin, which really felt far or isolated because it was behind the Iron Curtain. Prague felt far away—when the Wall went down, it turned out it was just less than a day’s drive. It freaked people out.

Part of this project of remaking or self-construction, at least within the plot, is possible because of a certain amount of economic comfort. High Cotton was an examination of that comfort, and of the black bourgeoisie. But this book takes that as a given, not an object of inquiry.

The family, meaning the elderly relatives, in High Cotton are very close to their models. But I didn’t know them. I never had these conversations with great uncles or—

So they have autobiographical models?

Yes. They left text. In a way I always thought of High Cotton as not built on folklore, because there are no oral stories, no one is telling stories on the porch, it’s not that kind of family. But they left these memoirs and I sort of regret not doing more with them. I certainly didn’t understand my great-uncle’s memoir at the time. For one reason, it was four hundred pages, typed in capital letters, single-spaced, and he only used initials. So it took forever to figure out that this is Johnny Hodges, this is James P. Johnson. I found his memoir in my grandfather’s vacuum cleaner, because he had suppressed it—I assume because my grandfather was writing his own, and he had a very slim volume called Romance of a Nobody, which my father always warned me has got nothing to do with the truth. So in Black Deutschland, I wanted Jed not to be like the narrator of High Cotton. I don’t know if I succeeded or not, but I certainly wanted his story to be different and the family to feel different. In High Cotton, they’re not part of the black elite. It’s education and bookishness that they’re descended from, it’s Reconstruction black colleges and the black church—it’s not light skin, barbers, or anything like that. In Black Deutschland there’s no emphasis on where anyone went to school, that’s just not there, and the family doesn’t have the same kind of Du Boisian commitment. The mother comes from a Marxist or radical house, and the father is. . . unidentified.

But the parents are committed to blackness as a project. The mother has an activist bent, and the father believes in rectitude in a rather old-fashioned, patriarchal sense. In Jed’s telling, they’re so stony, always recoiling from intimacy. One senses that it has something to do with having to live with such a constant sense of purpose.

That’s probably true. I mean, the family is meant to be somewhat eccentric and unacceptable to the black bourgeoisie. They just don’t quite fit. Maybe this is personal, because I don’t know a normal house—for me, everything was always a little bit off, not right, and that had nothing to do with anything except that people were crazy. So the question is, Why were they crazy or what drove them crazy? And probably being black in America did that for many people. Because it makes you live with lots of sets of strange things, or it used to. Maybe this has changed, or is changing. Class in black America has always been difficult. It was easier when everything was on the black side of town, these hierarchies, because as far as whites were concerned you were just black, it didn’t matter that you had a Phi Beta Kappa key on you or not. In fact, they didn’t like it if you did. I find now all of that slightly obscured by people. . . young blacks are rejecting this American dream or the conformism of it, but still everyone believes in getting paid, so it’s sort of, the materialism has liberated itself.

In your piece on Ta-Nehisi Coates, you mentioned that part of this new (in some ways desolate) mood is because unlike now the 1960s, and the environment of the New Left, actually offered an alternative—racial analysis was accompanied by some sense of opportunity. But you claim that now, if pan-Africanism and communism have been relegated to the historical dustbin, that righteous rejection has nowhere to go. And your novel actually takes place within a gray period in which the dreams of the ’68 generation have been defeated—and yet the Red Army Faction still exists. I guess all these world-historical realities that used to be so salient become kind of muffled by Jed’s psyche, but also by the strange emptiness of everyone’s political gestures. Dram, Cello’s husband, used to be a leftist. Manfred, Jed’s early love interest, used to be a leftist.

They weren’t students anymore. The Reagan reaction had been underway for a long time. Certainly one of the reasons I left was because that Reagan-Bush time was very unpleasant. Anyway, that disillusionment and feeling overwhelmed by the reaction is there, but at the same time Berlin was this free city, and these anarchists and environmentalists seemed to have a philosophical point to the way they organized their lives. There was still very much this kind of living by principle, if you wanted to. It wasn’t just that people went to Berlin to be free, there were also people in Berlin who were still building an alternative in their heads, because real estate hadn’t happened.

And that bohemian alternative seems to me resolutely, almost resentfully, provincial. The dreams are no longer of world revolution or grand societal transformation but about exempting yourself from what you see as a corrupt culture.

But isn’t that black expatriatism?

Exactly. And the novel is set at a time that has been referred to as the “end of history.” In a rather shallow way, I noted that history is precisely what Jed is trying to escape. Yet the narrative keeps circling back to Chicago and elements of his childhood that acquire new resonance when he’s in Berlin. Do you think your characters are manifesting a resistance to history as such?

Jed is much less oppressed by black history than the narrator of High Cotton was. Because he’s younger than Jed and it’s the past, which has a kind of sanctified weight. I think for Jed that’s sort of less, and it’s maybe that black represents a certain straightness, in all senses of the word, for him. And white is where he goes to be gay, or free. Even though in the book he doesn’t connect with any white guys: It’s always black guys. And I don’t know if he’s come to escape blackness so much as a class performance of blackness. His brother has no trouble with it: He’s married to a white woman.

But if he goes to Berlin to express some anarchic desire that can’t be accommodated within the straitjacket of black middle-class respectability, I think it’s interesting that AIDS dogs the novel as this tragedy of intimacy. The spaces of the novel are all carved up into privileged or non-privileged sections—there’s that affinity between Berlin, a city cut in half, and Chicago, the most segregated city in the US—and there seems to be a weird connection between the segregated city and the threat of disease.

That’s in part because Black Deutschland is a work of cultural memory—not my memories, I’m not from Chicago or anything, but this feeling: What was AIDS, where was it going to go? And at the time, the early and mid-1980s, the predictions were that it would become a worldwide epidemic. People tried to carry on or be cool, but I remember, at least for myself, there was a great deal of dread in the background of what you were doing, what you used to do, or what you had done. It colored what one did, and so of course it’s in the back of Jed’s mind. And it makes him sort of unable to be this predator he wants to be.

It’s funny to see how homosexuality was talked about. Cello and Dram congratulate themselves for their cosmopolitanism in tolerating this fallen gay relative, yet he can be quickly banished under the banner of AIDS. “You can’t live with me until you get the AIDS test,” or “Oh, you’re doing drugs”—it’s all part of this partially imagined seamy underworld that, as sophisticated people living in the wake of the 1960s, they must acknowledge. It wouldn’t do to be stuffy and bourgeois, but it’s interesting to see the ways in which they measure the distance between themselves and this almost avant-garde way of living.

Well, again, I was trying to be true to the period. But I also think that something like AIDS would expose the essential conservatism of a certain kind of black America, even one not connected to the church. Still, at the time it was a problem. Jed comes from a house where there are all these people in rehabilitation, these social projects, but they don’t cross any gender expectations. The mother works with battered women, but it’s battered women, the father watches sports, that kind of thing. And they don’t really want to deal with that side of him. I think that, years ago, in coming-out literature and coming-out films, the anxiety of the parent about what kind of life the child would have was very pronounced. Now, though, you tell your parents you’re gay and they want to meet your boyfriend. Next door to us is a gay couple half our age, also black and white, camera-ready in every sense of the word, and now they have two kids. One day before the second one was born I saw the white grandparents coming down the steps behind the two guys and their son, smiling away. They couldn’t care less that their big white son is gay, or that he’s married to a black guy, in fact, they’re the ones who insisted they get married. All they see is that he has the American dream. He’s got this beautiful house, this beautiful kid, a great husband.

“Is this my beautiful wife?” Not quite.

They’re fine with it, you see—parents are completely freaked out until the child is in some ways settled or moving in a direction the parents can recognize. It turned out all these people wanted the freedom to be ordinary, to get married, and this ideology that gay was different or alternative is as forgotten as communism. Gay became socially OK, because there were just too many gay middle-class people. So I can’t really tell who is and who isn’t from just looking at them, ’cause a lot of straight guys are wearing the earring and wearing these clothes and talking about, I don’t know, Cocteau.

That exquisitely differentiated microculture of male homosexuality makes possible someone like Hayden Birge in Black Deutschland. His significance is contingent on this highly precarious little world of gay aestheticism.

A little bit. He’s the one who’s always got something to say about Stravinsky or Ravel. Jed is trying not to feel rejected by him, since he would never have been in the running with Hayden. The whole book is about, really, Jed’s inability to find the intimacy he’s looking for. Or even the thug he’s looking for. These are all ideas somewhat derived from Isherwood—he’s trying to live out the fantasy of a book about another time that can’t be reclaimed, so he’s somewhat missing his own time. But then again, this is the Berlin effect. People are there partly for the historical fantasy. Berlin was where people wanted to go and hang out in the unresolved past, in a way.

And the Rushdie affair provides a tidy echo to Jed’s flight to a European capital.

Totally. That’s what it’s there for. There are these people who are real exiles one way or another, and this again is another literary idea Jed’s acting out. At some point he does sort of say, “they all felt real and I felt like I was just imitating a book.”

And yet, as soon as I started reading the book, memories of Saladin Chamcha, one of the protagonists of Rushdie’s book, emerged. But that book ends with a demonstration organized by the Communist Party, whereas the moment of political climax in this book is precisely the opposite.

The end of it. Yeah—I hadn’t thought about that either.

I guess I’m imposing things.

No! Writing a book is a bit like making a sandwich: If you press down on the bread, you’re not sure what will come out on the sides. You hope it doesn’t make you look stupid. So you try to make sure that the world you’re creating on the page doesn’t have any punctures in it where the air escapes. You do your best, and if there are things that come out that you’re not aware of, or didn’t see at the time, so much the better. It’s not supposed to be the kind of thing that you get all at once, or need to. It’s written with deliberate holes—or things unanswered, I won’t say holes—so if there are things that come out, I can’t control them.

Tobi Haslett is a writer living in New York.