“I’m mortified to be on stage,” Bob Dylan said in a 1977 interview, “But then again, it’s the only place where I’m happy. It’s the only place you can be who you want to be.”

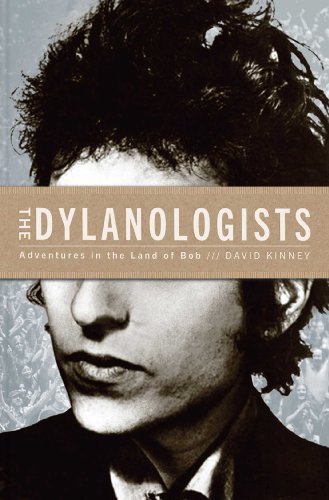

It’s from this conceit—of Dylan’s infamous reticence and the many personas he’s adopted over the years—that David Kinney founds his fascinating inquiry into the world of obsessive Bob Dylan scholars, The Dylanologists: Adventures in the Land of Bob, which comes out in May. Kinney, a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist, is no stranger to infiltrating obscure subcultures, as he did in The Big One: An Island, an Obsession, and the Furious Pursuit of a Great Fish (2009) an account of an extremely competitive saltwater fishing tournament. In his forthcoming book, the elusive subjects are both Dylan and the people who have dedicated their lives to “getting” him.

I spoke with Kinney about what compelled him to write the book, the places it took him, and we also delved into some philosophical questions about Dylan’s performative aesthetic—and, of course, I had to ask about that Super Bowl commercial. Though Chrysler’s nationalist ad fell flat, anyone who loves Bob—both the man and the myth—can agree with the commercial’s subtext: There really is nothing more American than Dylan.

What drew you to this subject: was it a personal connection? Do you consider yourself a Dylanologist?

Going into it, I’d say that I wasn’t a Dylanologist. But the subject fits in with my last book about fishing enthusiasts—both are about obsessive subcultures. I’ve been a Dylan fan since I was a teenager and went to a lot of shows. I got the sense, early on, that there was a larger community out there. You’re listening to a song, for instance, and you’re curious: What does this mean? Has anyone written about what this song is about, because I don’t get it? And I went to some online forums where I’d read pages and pages of discussion dedicated to “Desolation Row.” So, I was always interested in Dylan.

It began when I was casting around for another kind of obsessive subculture to write about, and the world of Dylan scholars seemed like a natural fit. I’m not sure you can really tell from the book, but I got kind of obsessed myself.

When you discovered all of this scholarship about Dylan and learned about the Dylanologists, did you find that it was difficult to earn your way into the inner sanctums of the subculture?

It depends. There’s a group of people who say they’re “completists,” as in they have everything Dylan has ever recorded, and they usually have some sort of inside information. As you get further away from that group—people who are not less interested in Dylan but they’re not as tied into the network—it gets easier to sort of break in. It was hard, though, with some people in this world. It was difficult with The Big One as well; I was an outsider, an off-islander going to Martha’s Vineyard, and that came with its own challenges. There was some of that here as well, and I had the impression that some fans were emulating Dylan. They were guarding their privacy just as much as Dylan does.

What do you think it is about Dylan rather than other singer-songwriters—like Lou Reed or Leonard Cohen—that inspires the kind of obsessive scholarship you see with Dylanologists?

I think one thing is longevity; that he’s still producing original work and he’s been doing it for fifty years now. There’s enough variety to it that there’s always something new to explore. If he’d just continued making folk records for fifty years people would have said, “OK, I get it,” and moved on. Even this last record, Tempest, was different from what came before; it was a different persona—so I think people respond to that. Also, the elusiveness —both elusiveness and allusiveness—of the lyrics allows you to listen to the music a bunch of times and have a different reaction—a different sense of the song. There’s a kind of mystique that doesn’t go away, and you can dig and dig and dig, and that’s rewarding. That’s probably what makes it more scholarly than, say, Springsteen. You can listen to Springsteen and get what the song’s saying—you might love it and want to hear it over and over again—but I think there’s something different with Dylan.

That’s a really interesting motif throughout your book: the notion that people can ultimately “get” Dylan. Do you think it’s even possible to get him, since he claims he does not want to be understood, and says in his memoir that no one will ever understand what he’s done?

I guess the people who would say they get it are talking about the idea that there’s these multiplicity of identities and you can’t pin him down. You have to understand that aspect of his work, and therein lies the key to understanding Dylan, as opposed to thinking, “Oh, he’s a protest singer,” or “Oh, he’s a folk singer.”

You recount a really great moment when Dylan realizes that Woodie Guthrie, his idol, can’t really understand him in the hospital, and he likens their visits to a form of confession. Some of Dylan’s superfans seem like they don’t want to listen to Bob Dylan as much as they want Bob Dylan to listen to them, to “get them” in a way. Did you see that kind of radical inversion?

That’s tough. It depends, because there are different types of fans. I mean there are the ones who are like Bryan Styble at the end of the book who went and searched for a personal encounter with Dylan. I can’t really relate to that because it’s not something that I would do, and I think that’s probably true of 98% of the people in this community that I met. But, for somebody like Styble I think there was a sense that he wanted access, he wanted to be recognized. You see that also with Elizabeth, the psychologist from Santa Barbara, who talks about how frustrated she is that her “relationship”—a long-distance relationship—with Dylan over the years, is one-sided. He doesn’t know anything about her, or even that she exists. And, she doesn’t necessarily know anything about Dylan, the man, and that’s just intensely frustrating for her. I thought that was a pretty poignant moment.

There’s definitely a number of those throughout the book—people desperately wanting to be understood by him.

Right, and I don’t know how far you’ve gone into the Dylan world but that was sort of the whole deal with Larry “Ratso” Sloman’s book in 1975, On the Road with Bob Dylan. He was hired to cover the Rolling Thunder Revue and everyone’s treating him like a dog. [Laughs] At some point he says there’s a confrontation in a hotel lobby, and Dylan finally comes over and says, “What is it you that you want?” And he’s like, “I need access! I need access!” I think there’s an element of truth to that for some of these people who follow Dylan around on the road; they’re trying to get into his circle.

I thought there was this really funny moment in the book when you’re quoting all these guys who have dedicated their whole lives to compiling and collecting everything Dylan, and then they admit that his music and performances weren’t really very good for about fifteen years. Why do you think the fervor of archiving everything for Dylanologists didn’t wane during that period?

I think there are two different things. One is there’s no accounting for taste, so some people like that stuff [Laughs]. The other thing is there is a collecting impulse that takes over, and a number of these completists that I met have this impulse to own everything. Mitch Blank calls it the collector’s gene. I think he calls it a sickness too. It’s not necessarily just Dylan, some of them collect other things as well. But there’s also another explanation I’ve heard that appeals to a historical sensibility. It’s the idea that Dylan is important and we need to save all this stuff, not necessarily for ourselves, but for later generations. That there are going to be scholars later on who are going to need every recording they can get their hands on—just in the way that we wish we had access to more material from Shakespeare.

That does kind of raise the question, ultimately, of the capital “T” kind of truth behind examining Dylan, and the idea of “getting it.” When I was reading The Dylanologists I kept wondering about why you thought Bob Dylan wrote his memoir, Chronicles: Volume One, because he blatantly borrows phrases from obscure works without citation, but it seems like there’s an intentionality to what he’s plagiarized rather than it being simply random.

I think Scott Warmuth has shown that it’s not random, and hopefully that comes through in his chapter, but that work is ongoing. In a way, all the interviews Dylan has given over the years have been a kind of performance art that fit in with whatever character he was inhabiting at that point. They go from being confrontational to friendly, but they’re consistently calculated in some way. I’d argue Chronicles is a piece of performance art, too. As I say in the book, anybody who expected him to play it straight wasn’t paying attention. And some of it was Dylan playing with everybody else’s attempts to tell his life story—I’m going to make up the best story I can [laughs] it probably won’t be true. People have been very enthusiastic, though, about a second volume of Chronicles, but they’re still waiting for it.

Since you said you became a kind of Dylanologist by the time you finished this book, I’m sure you were tapped into the network when he showed up in that Super Bowl ad. Did people know that was coming, and how did they react to it? Or did they just see it as a high-paying gig that didn’t really mean anything?

You could argue that was performance art as well, and there were people who did. There were people saying he was just doing it for the money, and there may be an element of truth to that. There were people who actually bent over backwards to say that he was using this commercial to subvert commercialism. So, the reactions ran the gamut. It’s interesting, whatever he does seems to generate controversy and always has, and, in some ways, it seems that’s the goal. He doesn’t want to do anything that’s going to be like, oh, well there was just another Super Bowl commercial and we’ll move on now. I think he wants to get that rise out of people. But in some ways that’s predictable.

In the book, there are some pretty wild characters, so I was wondering what sticks out in your mind—

Yeah, the really wild ones I left out. [Laughs]

Well, then those are the ones I want to know about!

It’s interesting, I had heard about Bill Pagel very early on, and I was really interested in meeting him, just because the fact that he ended up in Dylan’s old hometown, living right there on Dylan’s street sounded so amazing to me. He invited me into his house and was generous with his time, showing me his Dylan collection—including Bob Dylan’s highchair. Everybody’s first reaction is, that’s crazy, and he knew that—it was the first thing he said to me—but, I think he’s got that collector’s gene. He’s come around, though, especially since he’s been in Hibbing, Minnesota meeting the locals there and rubbing elbows with people who knew Dylan back in the day. I think it has maybe changed his perspective on what his collecting is about, and now his larger goal is collecting this stuff not just so it will sit in his house, but someday go to a museum and be on public display.

Given Dylan’s notorious reticence, if you could have had the opportunity to ask him a question or interview him for this book, what would you have said?

That’s a good question, and not one I ever really even considered because I was sure it wasn’t going to happen.

Did you try to contact him at all?

I did, but his interviews have become performance art, too, in a way. He does still do a sit down with somebody when a new record comes out, but it’s a hand-selected person like Mikal Gilmore or Jonathan Lethem, who is called and brought into a hotel room or a restaurant to have a discussion. Anyway, he’s been asked about his fans over and over and over again, so I had a wealth of material to work from. Just as I was finishing up the book he did that interview with Rolling Stone and was asked about some of the plagiarism stuff and that was helpful, and he gave that now infamous line about the “wussies and pussies” who criticize him, which was just hilarious.

Lastly, with all of Dylan’s deliberate performance art and re-invention, do you think behind each of those selves that he performed he genuinely believed he was that character?

You’re asking if he was sincere?

Yeah—if behind all of the different performances there’s a kind of sincerity within each identity he latches onto. If it was authentic in that moment, or if it’s all just a deliberate ploy.

Well, that’s the $64,000 question, isn’t it? (Laughs) I would argue there was sincerity behind each of those changes. There’s a restlessness to him. It couldn’t have all been play-acting.