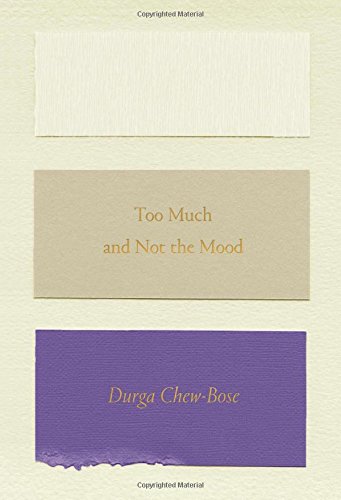

“Should I try to change my pitch?” Durga wonders, in consideration of her natural speaking voice, in an essay called “Upspeak.” “Should I try to sound more staid?” She asks her father how she could learn to speak differently. Easy, he replies: “Stop reacting to everything.” But then there would be no book for an essay called “Upspeak” to be in, and happily there is a book, Too Much and Not the Mood, a first collection of fourteen prose pieces in which Durga reacts to, and is acted upon by, the whole of quotidian life, sussing out the unobvious in sentences often as pixely and coruscating, as microcosmic and animated, as the gifs we use to signal quick appreciation. A critic who prefers the term “enthusiast,” an essayist who worries she’s really a poet, Durga is an unrivalled player of what Doris Lessing, in The Golden Notebook, calls “the game.” In “the game,” the writer-protagonist, Anna Wulf, tries to name and “create” every little object in her bedroom, ditto the bedroom as a whole, the house, the street, the country, and so on until she grasps the round world, holding in her mind “a simultaneous knowledge of vastness and of smallness.” Anna is the most particular person I’ve met in fiction; Durga the most particular person, and writer, I’ve met in life. It’s no easier for me than it is for her to see why Durga Chew-Bose should have to change.

We have been friends for five years, since a few months after I moved to New York. I saw her picture on Twitter, felt that she was beautiful, and, on a high-summer night, met her at Spain to drink the city’s cheapest red and begin a long correspondence. In “Heart Museum,” the momentous, unstoppable ninety-page essay that opens Too Much and Not the Mood, Durga asks more questions, questions for the end of being young: “Did I discern between admiring and enjoyment? Did I try on a dress? Even once? Did I disturb some peace? Experience some peace? . . . Was I a body? And did the boundaries of my thighs and the span of my arms inform my flight, or were they limbs only?” And: “Did I recover from the minor tragedy of gifting someone I love earrings she will never wear?” I did in fact wear those earrings, once. I hadn’t worn a pair in six years, and the holes in my ears had grown over, but I used the fishhook of one jet-and-silver drop earring to repierce both lobes. A few hours later the left lobe was definitely infected, so I took out the pair, put them in my pocket, and never saw them again; she never knew why. That one is as good a story as any to encapsulate best friendship.

The other day we went to the café upstairs at Metrograph, the art-house cinema where, in conjunction with the release of Too Much and Not the Mood, Durga is hosting a screening of Barbara Loden’s Wanda, followed by a book signing, on April 13. She wanted to talk first about what I was reading, then about what her students were doing in the writing course she teaches at her alma mater, Sarah Lawrence College. We talked for three hours, or seven glasses of wine. I abstained from transcribing any of the gossip, because Durga is not mean, and most of my jokes, which she does not think are funny.

Durga Chew-Bose: We’re ordering off a menu called a “Writer’s Menu.” You can’t put this in the interview.

Sarah Nicole Prickett: I can. It’s funny, even though I always liked writing, I refuse to think that “writer” is an aspirational identity. A stranger emailed me to say that she felt guilty because she has a degree in literature and is working in an unrelated, professional field, instead of writing for lit mags. I thought, like, why?! You have money and vacation days. Go read a book. Don’t say anything about it. Seems deluxe.

D: Trust me. I know. I would love to do that.

S: Me too. Live by the sea.

D: I was rereading this Lydia Davis interview where she said that when she was a kid, she wanted to grow up and be a reader. That’s the dream. I think that’s why I like teaching, because the students spend so much time reading and so little time responding. They write everything at the last minute, and because they’re not constrained by anything but time, they just shoot off into space and write the weirdest, brilliant things that they don’t even know are weird or brilliant.

S: Ugh. To be able to write—to be good at writing, but not know what good writing is, or, like, to not know how things are written. That’s alsothe dream.

D: I give the students questionnaires. I’ll ask, What’s your least favorite fruit in a fruit salad? Or what’s something you did competitively as a child? The last compliment you received? Your favorite collective noun? Your least favorite color to wear that everyone says you should wear? The last celebrity death that really shook you? It’s a fine balance, being curious without having an agenda.

And it’s always the questions I think are the most benign that induce the most weirdly profound answers. Once I asked, What’s the perfect sandwich?, and one of my students wrote, “Lentil soup and feeling contradictory today.” She answered it, but in a way that made it clear she didn’t want to. I started laughing, like of course you’re my student.

Or when I think I’ll get all different answers, it’s the opposite, like I asked, What’s a word you always misspell? So many people said separate, and I said separate too.

S: Are the olives okay? There were no olives on the “Writer’s Menu,” but I told the waiter you would need them, so he brought some that are for a Niçoise and some from the bar.

D: I’ve never had a bad olive.

S: Imagine? “The Bad Olive.” The title story in your debut book of short fiction. Although, already, in Too Much and Not the Mood, I feel like you’re almost writing fiction.

D: That’s what Jonathan Galassi says. I’m a fiction writer writing nonfiction.

What I think, when I look at this book, is that I’ve done something I never really do, which is: I’ve taken advantage of a situation. I wrote exactly what I wanted, or as close to exactly as I could get. I wrote it to my friends and to my family, and I forgot the whole time I was writing it that other people would read it, too. That writing a book means a stranger can pick it up and examine my association of Charles Mingus to my father’s shirt, or my understanding of a childhood fishing trip, or a trip to Calcutta. I never thought, What do other people want from my book of essays? I never let that thought get in my head.

S: The notion of disappointing someone you don’t personally know is very funny.

D: Also, here’s the thing: I moved to Montreal in April of last year, so I was writing away from book people, away from people talking about books, away from people writing alongside me about similar things. I went a little free and crazy with it. Like, it’s Durga concentrate, like a frozen can of orange juice. People who know me will like it, but people who don’t know me will find it a lot, or worse, they’ll read it and think they do know me.

I often write about learning more from other people than from myself. It’s unfathomable to me that someone—a stranger—reading this book is learning about me. It’s weird doing interviews and being asked questions about “Sarah.” Who? I have to remember it’s you.

S: Maybe if you had put “Sarah Nicole”! But then I would be “taking up space,” which isn’t historically something you enjoy. It’s interesting who you name in your book, and who you don’t. Tavi [actress, writer, and the editor-of-chief of Rookie], who is widely recognizable by her first name, is never named. Men you’ve slept with are never named.

D: Well, mostly I want the stories to have more shadows, and to do that I have to be careful where to shine a light, on who or on what. It sounds right to say “Katherine’s pear,” because it situates the pear. It sounds more right to say “my friend who has a play on Broadway” than to say “Tavi,” because “my friend who has a play on Broadway” puts us literally adjacent to Canal Street, where we’re getting our auras read. I actually write about you a lot and don’t name you. It would have been terrible to say “Sarah’s wedding” when I wrote about the silver shoes you wore that day.

Here’s the thing: The more anonymous someone is in my writing, the more specific I can make her or him. I made my ex-boyfriend so specific in this book. I put in things that his future wife will never know.

S: If he’s lucky!

D: My friend India texted me after she read it and said, “I feel like the star of your book is your dad!” It was nice that she felt there was a star. India is my most earnest friend, the one who doesn’t write but goes to a book club, and I was so charmed by her takeaway. It’s true, he is in some ways the star of my life.

This popcorn tastes like an Indian snack called dal moth. It has a kind of spice that makes the tip of your tongue feel aflame. You might not like it.

S: I like it, silly.

You sent me the notice of your book in the Times, and it said it’s about “family, friendship, self and identity.” I was like, “Is it?” I thought the book was about perception, or about feeling as a verb but not a noun. I had no idea Wong Kar-wai is your hero.

D: He’s so not my hero. I don’t know why the reviewer said that, but I was grateful to be close to Mary Gaitskill on the page [of the Times’s book section].

To me, the word about is a weird word in criticism. My book is not about. My book is. It’s about interiority, correspondence with myself, correspondence with the people in my life. It’s about everyone who’s ever affected me. It’s about memories and possibility. I always tell my students that when you remember something, you’re also making something newly possible. Writing is, for me, a form of retrieval.

S: There’s something else funny, on the jacket copy. “What it means to be a first-generation, creative young woman.” Comma between first-generation and creative. What this says, according to its syntax, is that you’re a first-generation young woman. You’re Eve, describing an apple seed.

D: I’m the first generation of woman! Didn’t you know, Sarah?

“First-generation” is about to become the new thing Céline puts on sweatshirts. “First-generation woman.” Five-hundred-dollar sweatshirt. Although, other people tell me I’m actually second-gen. I’ve heard it both ways. I feel like which generation you are is defined by where you spend your childhood, and my parents spent their childhood in India before moving to Canada. My brother and I were the first generation to have a childhood in Canada, so my parents always say that I’m first-gen.

S: I should ask you questions about how you wrote the book before we get too drunk.

D: I don’t want you to feel like you have to ask me questions about book writing!

S: You wrote a book. Am I wrong about this? If you would like to introduce me to the person who wrote this book, I would be more than happy to direct my questions to her.

D: She’s taking a really long nap.

S [laughing]: Well, it’s funny you say that, because, as I’ve said to you before, I loved the moments in the book, often at the end of essays, that make you wonder whether any of this happened. At the end of “Heart Museum,” you wake up in a cab at the heart hospital in Mumbai, which the driver is calling a “heart museum,” and I’m like, “Wait, this did not occur.” Or in “Moby-Dick,” you’re reading alone in the library, and the janitor comes in to vacuum, and we wonder how the whole day has passed.

D: Those things did happen!

S: I know, but whether or not memories are tied to facts is irrelevant to form, and your forms are more like short stories, or the really short ones are like character sketches, as in “The Girl.”

D: “The Girl” is like a composite sketch of myself. When I read Edmund White on Marguerite Duras, saying that all she did was repeat her own story in her own words, I felt a huge weight being lifted from me. Before that, I thought that writers were not supposed to repeat themselves, and I was worried because that’s all I do, too. My version of repetition is repetition not of a big idea, but of a feeling or a fear.

S: It’s exactly the part of the book where I felt you come closest to being Duras. But it’s also the closest you come to being a woman in the more current or commercial way of quote-unquote women essayists, where you almost reach the inevitable point of addressing where you stand vis-à-vis a man, or men in general, and it’s the only essay addressed to someone you don’t love, so it feels confrontational. “The girl does not exist.” Not “The Girl,” not yet the woman.

D: Closest I’ll ever be to Britney Spears. But it’s also me confronting myself. I’m quite comfortable confronting my fears, like the fear of being too difficult, in writing, but not in real life.

I remember exactly what I was thinking when I wrote the line in “The Girl” about having sex and feeling like a tourist. I was sleeping with someone, and whenever I woke up at his place, I wanted to go to a museum. I was like [gulps], “I can’t share that with people.” It’s so embarrassing.

S: I loved it.

D: Is having a book embarrassing?

S: No! It’s only embarrassing to say you’re “doing a book.” Personally, I’m afraid of “doing a book” I don’t want. Like how mothers are afraid of not wanting the baby after it’s born. Or like, afraid the baby will be ugly. I would hate to write an ugly book.

On the other hand, it can be embarrassing to read the loveliest words out loud. Two of the essays in your book, the one about being miserable and the one about things you can’t unhear, were originally written for readings. Do you think a lot about orality in your writing, or do you want the prose to feel like you’re in conversation with a friend, or a reader? I feel like you can have prose that looks lovely or you can have prose that sounds alive, but you’re excellent at doing both.

D: I like to give myself a project or a challenge. For those two readings, I took the opportunity to write pieces that would have a more sonic sensitivity, and that would be more conducive to performance, because I’m not a natural performer. I put in cues for myself, like extra italics, punctuation, phonetic spellings or misspellings. That kind of playfulness makes an art of reading, both for me as a reader at a podium and, hopefully, for a reader on her sofa at home.

Dialogue, though, is terribly hard. I wish nothing more than that I could capture our cadence after two glasses of wine. I’ve been reading Vita Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf’s letters, and sometimes I read them out loud, because they have all this flair, these dramatic tics, like they’re reading to each other from opposite ends of a stage.

S: Do you read your own writing out loud, even if it’s not for a reading?

D: Always. Same as you. I care about rhythm more than I care about ideas. I’m ashamed to say that, but I can’t be that ashamed, because I refuse to change it. But the rhythm changes irreparably when you’re reading it not to yourself, but to others. I did a reading at Housing Works the other day and right before I went up, I crossed out so many lines.

S: Wait, when? Why didn’t you tell me?

D: Well, it wasn’t just for me. There were other readers.

S: I’m aware. I have seen a reading before. I still would have come! Did people come up to you? Did they ask you questions after?

D: People were very nice and said they were excited about my book, but I was feeling nauseous and had to come to a screening here, so I ran out. It’s weird, no one tells you how to be your book. It’s not what I bargained for. This book is now as much a part of my identity as my shoe size.

S: Your shoe size is part of your identity?! What are you, Cinderella?

D: Meaning: It’s something I can’t change. There’s nothing in this book that puts me in a category, like film or feminism, where I can be an expert. The only thing I’m asked to speak on is being a woman of color. But that’s not the part of me that the book, for the most part, concerns. I don’t want to be a part of anything, ever.

S: You could have written a whole book on film. I hate saying this, but if you were a man…

D: I’ve done a hundred interviews with directors, I’ve written a hundred pieces about movies, and yet I still don’t feel part of the film world. That is maybe the one thing I do so desperately want to be part of, but I’m not. No one’s ever like, “Durga the film critic.” And all I do is think about film! I could only write about my own life by thinking about my life as a movie and describing it as if I were seeing it on a screen. I think I would be a better girlfriend if I didn’t see my life so damn cinematically, if I didn’t spend so much time thinking about how it looks to myself.

S: You arrived in a backwards way at writing in the first person, from writing those very adult-feeling film essays right out of college, never writing about yourself, never blogging, to now writing a book about private experience. Remember in The Dialectic of Sex when Shulamith Firestone says that—and I’m going to paraphrase this very roughly—women and children have been lumped together in political discourse and decision-making? Sometimes I think about how much of what is now celebrated as specifically “women’s writing” is also childlike. Like how imitating écriture féminine can feel like scribbling. Like how it’s common and acceptable to start sentences with “I want.” A child doesn’t know what other people want.

You talk, in the book, about editors encouraging you to say “I think” instead of “One might say.” You write that you’re someone who has “read enough ‘I’s’ in enough essays but has never seen ‘me.’” Maybe I’m failing to distinguish between women’s writing and internet writing. “It me” is also a childlike utterance. But to know who you are, to be able to clearly speak up for yourself, is not childish at all.

D: The first time I saw “me” in an essay was in Vivian Gornick’s Approaching Eye Level, where she says, “I had always known that life was not appetite and acquisition. In my earnest, angry, good-girl way I pursued ‘meaning.’” That was the first time I saw an “I” that I could relate to, because she called herself an angry good girl, and because I, too, was interested in the pursuit of meaning. I didn’t put myself in my writing because, until two and a half years ago, I didn’t know I could be an angry good girl. I associated the “I” with being sure of yourself and not being contradictory.

I remember my ex-boyfriend being upset after I wrote an essay about Barbara Loden’s Wanda, because he could sense that I might be writing about Loden because, like her, I felt repressed and overshadowed by my partner. I wasn’t using the “I” then, but I was writing in code about relationships. I was writing about a woman who doesn’t know what she wants, and knows very well what she doesn’t want. Wanda is a woman avoiding her purported responsibilities, like being a mother and having kids, and of course it’s reckless, and she’s easy to judge, but it was the first time I had seen a heroine impelled entirely by what she didn’t want to do, as opposed to being led by deep desires or passions. She drifts rather than strays.

Actually, Wanda is like Cozy in Kelly Reichardt’s River of Grass, and she and Cozy both end up with men who are criminals, but that’s not the point. The point is, watching Loden play Wanda, I felt a relief valve open. She’s distracted in a way I had never seen anyone be distracted. A woman who, when she finally breaks free, looks like a ghost instead of looking stronger. A woman who lives on opposing terms, similar to how an “angry good girl” opposes herself.

S: Female drifters aren’t big archetypes in American cinema. Although, I saw Thieves Like Us here yesterday, and the Shelley Duvall character marries outside the law, too. I kind of wish I’d married outside the law! It’s a way of excusing yourself from society. Marriage necessitates some kind of disappearance, though, in any case.

D: I have complicated feelings about wanting to disappear, because I already struggle with feeling invisible, and I know that visibility can be construed as a privilege, but I also never want to be fully seen. I even like, on occasion, to be misheard. What I struggle with more is being misunderstood.

Now that I have a book that is supposed to define me, I worry about the critic who thinks, “Why should I care about her life?” I feel like that’s saying, “Why am I spending time with this person?” Well, no one forced you to be here. Go home!

S: The argument about whether it’s narcissistic or whether it’s radical to write about your life as you see it, to write about yourself on your terms, is not as interesting as the art. Chantal Akerman casting herself in her first short film. Barbara Loden directing and starring in Wanda. Francesca Woodman being in all of her photos but you never really know what she looks like. These artists aren’t especially narcissistic or necessarily radical. They’re resourceful. You’re the resource. You don’t cost anything. There’s a low barrier to entry for writing or art about yourself.

D: When I was writing about film, editors were always like, “What’s the point, Durga? Where are you going with this?” It’s funny, people who aren’t writers or editors—and aren’t even necessarily my friends—don’t wonder what the point is when they read my book. Like Jake, who is the forty-one-year-old director of Metrograph, was so moved when he read it, and it wasn’t the film stuff that moved him, it was the stuff about parents.

I was texting with Haley Mlotek one day, and I was saying I was worried about how personal the book was becoming, and she said, “Don’t worry, you’ll find your readers. Your job is not to find your critics, but to find your readers.”

S: Yes. Although, I would like to find my enemies before they find me.

D: I only want to find my enemies if I’m in the same room as you. But I don’t think I have enemies. The only real enemies are ex-friends. I’m not ambitious enough, anyway, to attract anything more than silent animosity, or maybe I’m only ambitious enough for myself. People sometimes roll their eyes, because they’re like, “You have a book. You’ve decided to do things, and achieved them.”

S: By “people” you mean me. I’m rolling my eyes.

D: But I’m not trying to build castles in the sky. I wouldn’t know how. I turn inward and find the materials. Also, I want to have a life. I don’t need my life to be adventurous. I want to be in bed by 11.

S: But how is it not ambitious to name your book after a line from Virginia Woolf’s diaries? James Ellroy, in this totally nuts interview I love, talks about how Beethoven is the greatest artist ever in world history. Then he says he relates to Beethoven and, “If you want to identify with a great artist, go right to the top.”

D: Maybe my ambition is secret even to me. I don’t know that I identify with Woolf. I feel . . . connected to Woolf. She writes so much about tiredness. Maybe her tiredness is that she folds into a single day that whole doomed feeling of a life. I trust tired people.

S: And then she went to bed early. I always forget she was fifty-nine and not forty-nine when she committed suicide.

D: A good age to go.

S: Not dramatic. Not a midlife crisis. Kind of like going to bed early when there’s a party at your house.

D: Even less dramatic than that! It’s more like gardening early in the morning and then taking a nap before lunch.

S: Suicide is always a little dramatic.

D: Vita once wrote to Virginia that she missed her “damnably.” How perfect is that?

S: Very. Speaking of perfect, I want to know about the last little changes you made to the book. I love a last-minute word change.

D: Well, I took out the “Bic pen” in “Part of a Greater Pattern,” where I write about the stuff on my desk.

S [laughing]: You did not.

D: I did! You were the one who was like, “Durga. You do not use Bic pens.”

S: You’ve used Le Pen pens for ages. I do too now. I guess you can’t say “the afternoon light exaggerates my Le Pen pen’s worth.”

D: At one point in the edits, I read Christian Lorentzen’s piece about how he hates adverbs, and it totally scarred me! I was like, “Oh no, I love an adverb!” So I went through and made sure I had only two adverbs per page, if that.

S: What I associate with your style, in terms of things you do differently from how we’re taught to write, I mean taught by like, Orwell or Didion, is the way you do verbs. You love to “veer” or “venture.” Here [opening book at random] you have “the rude temptation of a crisp day: how it bullies.” Or here [opening book elsewhere at random] you have a woman who “flutter-blinks her lashes between strokes of mascara” or [on the same page] you have girls’ names that “pleat your memory with sing-song.” Most people confine fanciness to adjectives and choose from a more grounded set of verbs, but you animate every part of a sentence.

D: I know what you mean, but I feel like that’s me being an amateur. I can’t always explain my word choices, or maybe I don’t think of them as choices. I don’t know how real writers do it.

S: Durga, focus. We are doing an interview for a magazine, it’s called Bookforum. The occasion for the interview is that you have published a debut book of essays with a respected literary publishing house. The time to worry about whether you’re a real writer is over.

D: Fine, I’ll worry on my own time. What I will say, which has to do, again, with being a “nonfiction writer writing fiction,” is that I was insecure of the word essay in relation to this book. It doesn’t say “essays” on the FSG edition of the book, because I took it off. It says “part memoir, part cultural criticism,” but I still don’t feel like a critic. I feel like critics are supposed to be funny, or witty, and I’m not funny or witty.

S: You are funny, but your preferred mode of joke delivery is a valentine. You’re funny about loving people.

D: Yes, because all I ever want to express are my enthusiasms, most of which are about, or are directed to, the people I love. Loving people keeps you sharper, more perceptive. You want to claim that your love is original.

S: Except that what you notice about another person can say more about you. It’s the age-old paradox of criticism.

D: The only art I really love is art that begins with a single, inexplicable image. Like Polly Platt seeing Jack Nicholson with a pink balloon. Or like Andrea Arnold seeing a girl peeing on a carpet, and making a whole movie, Fish Tank, about that one image. I wrote “Moby-Dick” because I had an image of the library, the one at Sarah Lawrence, being empty at night, with the blue, dark carpet, and a janitor coming in not knowing a girl was there, and so I worked backward to remember what I was reading, what I was thinking.

Although, the other day I went to the library at Sarah Lawrence, and I looked down at the library carpet, and it wasn’t blue. I swear I remember it being blue. I thought, My whole book is a lie!

S: Was there one image you held in your mind as you put the whole book together?

D: That cover of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca that says, underneath the title, “Her Novel.” A picture of my mother getting off the Queen Elizabeth with a suitcase that says “Chew.”

S: I do wish the cover of your book said “Her Book.”

D: Rodrigo, the designer at FSG, says my book is an objet.

S: If something is beautiful, we think it’s an object.

D: You know when you go to a museum with a friend and it’s understood that you don’t have to stand side by side in front of every canvas? You can move at different speeds, occupy different corners, get separated, and it’s fine and relaxing because somehow when it’s time to leave, you’ll find each other. My favorite type of writing is like that, where it drifts in and out of different rooms, and sometimes ideas get lost or sentences sort of wander or drop off and the meanings and senses of things get separated, but it doesn’t matter. Like how after the museum, you can walk for a few blocks with your friend in silence, not pressed to speak.

Sarah Nicole Prickett is a writer in New York and the editor in chief of Adult.