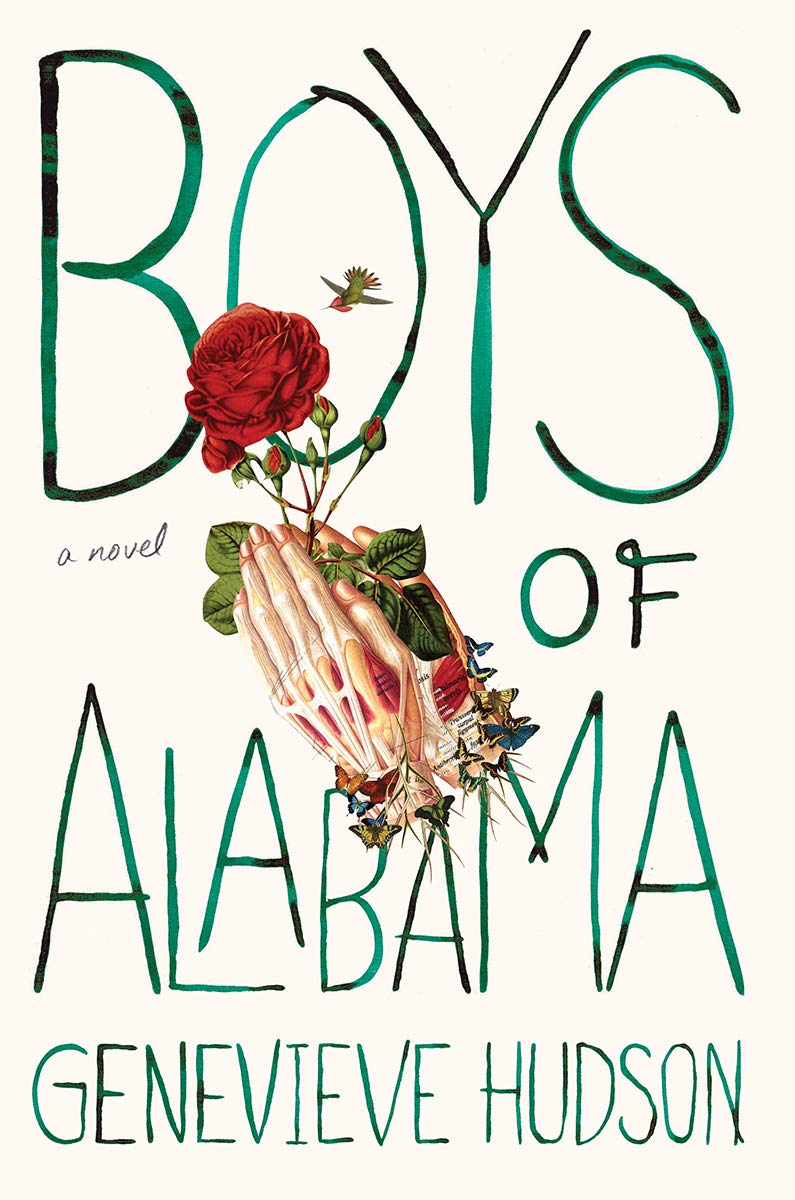

Genevieve Hudson’s debut novel, Boys of Alabama, tells the story of Max, a shy German teenager with a rare magical power, who emigrates with his parents to Alabama (Hudson’s own native state). There, Max finds a place rife with wonders and terrors beyond anything he’s ever known. It’s a slow-burning exploration of queerness and magic and toxic masculinity—of otherness and the yearning to belong—set against the landscape of the Deep South.

During the early days of the lockdown, Hudson and I talked about obsession, sentences that are more than mere load-bearing devices, and the innumerable definitions of the word “home.”

One of my writing teachers, Noy Holland, gave me a piece of advice I’ll never forget: “Write towards your obsessions. They’re where the gold is.” Do you feel you’re always circling certain themes, ideas, questions?

I relate to that sentiment a lot. I think we all have these central questions that we’re constantly trying to get to the end of, even if we never will. For me, these questions aren’t always laid out so obviously that I know what it is that I’m asking. Then, I pull back and see these same ideas cropping up again and again throughout my work. For example, the idea of what it means to feel like an outsider even in a place where you’re supposed to belong. What is it like to live with secrets? What is it like to desire something that feels just out of reach? I heard Alexander Chee once talk about how the queer experience can be that of a changeling; you kind of come into your new identity. In a lot of ways, you have bloomed into a new person with a whole new way of being in the world. That experience has endless fascination to me, and it comes up again and again in my work.

In the novel, Max is hypersensitive to everything—smells, sounds, the strangeness of the culture, even the particular quality of the air. There’s a sense that he’s an alien on a new planet. You grew up in Alabama—what was it like to write about it from the perspective of a foreigner?

I left Alabama when I was eighteen, and for a long time I wanted to put a lot of distance between myself and the Deep South. It was a complicated place for me that had brought me a lot of pain, and yet it still felt like home. When you talk about the South, there’s a rich sense of tradition and music and food and civil unrest that comes up in our cultural imagination. There was something about my place there—what it meant to grow up somewhere with that history and that lineage of pain and oppression—that I really felt I needed to explore.

I lived in Amsterdam for six years, and I would go back to the South, and bring my partner, who was Dutch. I think going there with someone foreign and seeing it through their eyes threw it into this new, stranger light. Coming back to the South after being away allowed me to look at familiar things in an unfamiliar way.

There’s an approach to writing called “defamiliarization,” where you describe something very common or ordinary, like a stone. Viktor Shklovsky, the Russian formalist, talks about how defamiliarization is an attempt to “make the stone stony” again. A stone seems so familiar to us that if somebody says “stone,” we don’t even really register it. The smoothness, the way it feels in your hand, the way it appears on the ground; we don’t even see it. So, how do you get a reader to be confronted with this familiar image in a strange way?

In Boys of Alabama, Max yearns to belong, yet in order to do so he believes he must erase those qualities that make him most special, which is something I think we’ve all experienced on some level, especially during our teenage years. Can you talk a bit about what it means to you to belong—to find a “home”?

This idea of home—where is home, what is home, and what does it mean to belong—is one of those circular obsessions that we talked about earlier. Periodically, especially when I’m engaging in more essayistic writing, I’ll have moments where I’ll dig through old journals and try to see what I was thinking at a certain point in my life, or what scenes were going through my head however many years ago. It’s always a bizarre experience to see the same questions come up for me over the years, even as I change and evolve and deepen as a person. One that I see come up again and again is this question of “What is home?” I’ve realized that home is very much something that you take with you. It has to do with developing a really deep sense of self, and a deep sense of belonging, whether you’re in the place that you were born or making a new space for yourself. In Alabama, where Max is a true outsider in a cultural sense, his sense of home is really thrown off. He is still grappling with this basic question of, “Who am I? What part of myself can I show to other people? What do I do with the secrets I’m holding?” As long as you’re in this deep, internal conflict with these basic parts of yourself, it’s hard to feel you can be a part of an external environment, or to feel safe enough to allow yourself to feel at home.

Let’s talk about the character of Pan. When it comes to the social and cultural mores of Alabama, he’s irreverent—and yet he’s still, for the most part, accepted by these football guys, being someone who’s “from” there. I found myself constantly revising my idea of who or what he was, whether he was “good” or “bad,” how he fit in (or didn’t), whether to trust him, whether he had Max’s best interests at heart.

What I saw growing up in Alabama—though I don’t want to generalize too much—was that no matter what kind of conservative or liberal family you came from, or what class, there was a sense that the kids you grew up with were familiar to you, and that familiarity also bred a sense of family. So, you could have a lot of difference in the way people were developing their identities, and there was a sense of protection and acceptance within that. Pan represents someone who was maybe on a path with these guys from the football team that was maybe going to lead to a more masculine, sports-oriented, God-fearing individual. But he, like a lot of people I was close to in Alabama, veered off onto another path. He became really critical of some of these traditions, and people in his community maybe laughed him off. There’s a line in the book where one of the football dads says that he’s just testing the limits of what’s OK—it’s just a phase he’s going through. But at the core of it there’s an acceptance. Pan is one of them, and there’s a deep and abiding love that goes along with that. He is complex, like all of us—there are parts of him that can be trusted, and parts that can’t. He is a young boy who is still figuring out what he thinks and believes, and how he’s going to be in the world. He has a lot of pain that he’s carrying in him, and a lot of fire, and I think he could be a dangerous person to get close to. That danger also comes from a sense of feeling outside of the place he’s grown up in; feeling he’s growing at a rate that’s incompatible with his community with, and having heartbreak, and all of these things. He’s trying to synthesize this, and find purpose, and it is coming out in ways that can be unpredictable. He’s an unpredictable person for Max to get close to. In my mind, he’s not a “bad” character, but he’s also not a “good” character. And those dynamics that defy an easy answer are the most interesting things to pursue.

I’m curious about your process when working on a novel as opposed to short fiction. Do you find there’s a considerable difference in the way you work when you know the project is going to be longer?

The biggest difference to me when I’m writing shorter pieces versus a novel is the scope of how you develop plot and how you pace things—those were the concerns that felt really new and exasperating and exciting to me, that I was trying to figure out and rework. Throughout all of it I was writing very slowly, and I was trying to think about sentences as I was also orienting myself towards these new, larger concerns of novel-writing. I care a lot about the sentences that I put down, and I think they really influence the way I move forward. Gary Lutz’s lecture “The Sentence is a Lonely Place” talks a lot about the role that sentences play in writing and the energy they bring to the page. He says something like, “they should do more than be load-bearing devices that carry along plot.” And he gives all these examples of ways that you can make sentences alive and unexpected and interesting and unusual. The sonics of sentences can propel readers forward in a similar way that plot can, by associations and sounds and rhythm. That lights something up in a reader that can create a forward thrust. I’m a slow writer because I’m constantly reworking my sentences. Each day that I sit down to write, I’ll read what I wrote before, and edit it on a sentence level for sound and compression. When I move forward, I let the sentences that came before speak to what’s coming next. A lot of it has to do with associations between sound and length, the consonants and the vowels, and how it’s all working together. It feels almost like I’m putting down music and it can be harder when you’re working on a longer piece, because it’s easy to get trapped on a micro level like that.

What were you reading while you wrote Boys of Alabama?

To me, reading feels like the lifeblood of writing. It’s so vital. It gives you the nutrients you need to be able to think about language in a way that would allow you to sustain a long writing project. I was at MacDowell while I was in the final editing stages of this book, and I read Sula by Toni Morrison. The language really inspired me in terms of strangeness and the integrity of sentences. That felt really important to sit with as I was editing, and to remember, “Don’t be lazy.” Every sentence needs to matter. Morrison’s work felt so beautiful and so crafted and so transcendent that I could not even imagine touching what she did, but it felt important to have something like that to strive toward.

Another book that felt like it was in conversation with Boys of Alabama was Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson. There was something about the language there, also, and just the strangeness of that story, the magic, the longing, the desire, the mythology, that felt like it had resonance with my thinking about my book. I didn’t actually read that while I was writing, but it felt like it was inside of me.

Annabel Graham is a writer, photographer, and illustrator from Malibu, California. She holds an MFA in fiction from NYU, and serves as fiction editor of No Tokens. For more, see annabel-graham.com.