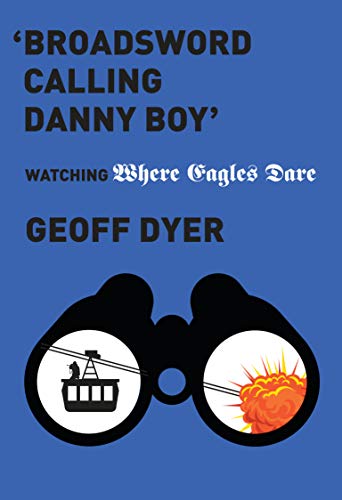

In 2012, the British author Geoff Dyer published Zona, an eccentric volume on Stalker, Andrei Tarkovsky’s vaunted 1979 film. Dyer’s Zona moves with pronounced energy between close readings and carefree riffs. Dyer’s new book, ‘Broadsword Calling Danny Boy’—just out from Pantheon—marks the writer’s second crack at book-length movie criticism. Slimmer than Zona, ‘Broadsword Calling Danny Boy’ offers a gleeful report on Where Eagles Dare (1968), Brian G. Hutton’s World War II entertainment about a pack of Allied soldiers (led by Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood) attempting to retrieve an American operative from a tightly guarded fortress in the Bavarian Alps.

Hutton’s two-and-a-half-hour movie, written by Alistair MacLean, coyly doles out information and motivation, toggling between patiently sustained action sequences and secretive back-room conversations that twist the plot. Dyer’s book follows Where Eagles Dare from start to finish, but frequently veers off-course into the author’s darting consciousness. Dyer spoke with Bookforum by phone about Where Eagles Dare, his book about the movie, and his process of thinking about a film he has adored since childhood.

With Zona, I feel like part of the challenge was finding a fresh angle on a movie that people generally agree is important. The new book is sort of the flip side, where you need to justify a book about a movie that is fondly remembered but not considered significant. What were the distinctions between those two tasks?

That’s the perfect point to start. The other thing to emphasize with Stalker is that relatively few people had seen it when I was writing my book—there were complications with the film’s licensing. There was one increasingly bedraggled print serving the whole of the Western world. So it was a film that not a lot of people had seen, but the few who had seen it loved it. Where Eagles Dare couldn’t be more different, particularly in Britain. It’s always on TV. It’s part of everyone’s consciousness. It’s not a serious film existing in the thin cultural air where Tarkovsky is, but it had been seen by a large audience. I think some people were pissed off by the Tarkovsky book, because they felt I hadn’t treated him with sufficient reverence. I feel that being reverent about anything is just worthless. In the case of Where Eagles Dare, it would be incredibly inappropriate to write in a reverential way. It was easy to write about this film in a lightheartedly, and you can easily see the absurdity.

If Zona reads like a book about an auteur, this one reads like a book about actors. You even write of Hutton that his “stylistic signature as director lies in the absence of anything that might permit us to recognize him as an auteur.” What was it like to make that shift?

In a way, Hutton’s work on Where Eagles Dare is very skillful, but invisibly so. One of the things I increasingly feel is the mark of a great director is rhythm. Often you go to a film, and within ten minutes you’re saying, “Oh my God, the bloke has got no rhythm at all.” It’s just clunking along. But with Where Eagles Dare, you sit down and say, “OK, I’ll watch it for a bit,” and then it’s difficult to give up on, precisely because of its rhythmic flow. It really does carry you along. There’s no particularly elaborate shots or anything like that, but it’s skillfully done. You’re right: I think our attention is on the actors. There’s a wonderful chemistry between Eastwood and Burton. It’s this combination of Burton, who is all voice, and Eastwood, who is all physicality—that beautiful rhythm of his walking and movement.

You make several references to contemporary cinema: recent war pictures; a note on the Where Eagles Dare hat-tips in Inglourious Basterds; the assessment that “action movies have become a form of explosive torpor.” Where Eagles Dare is a film you’ve been watching for decades, but to what extent did the current state of action movies influence the points you wanted to make in the book?

I wrote about exactly how many shots there were in Stalker. If you did a proper accounting, I suspect Where Eagles Dare moves at a much slower rate than contemporary film. In that respect—I say this partly as a joke—it’s still got a sort of Antonioni-like pace, compared to the rapid-fire cuts of contemporary film. But the main difference for me is that incredibly alienating thing: CGI. In Where Eagles Dare, although some of the back projection is clumsy, you always feel that the people doing the stunts are genuinely at risk. Gravity is felt as a major force in a way that it rarely is with CGI. The other thing is that when I go to the cinema now, and there are previews of action films, I’m struck by just how unbelievably boring they are. Where Eagles Dare is not at all boring. I say that with confidence because, even if I’m unsure of lots of things, I know that my capacity for boredom is up there with some of the most easily bored people in the world. I take that, again, as a sign of some invisible quality that Hutton must have.

The book traces the plot of the movie, and then you use that structure as a means to go on your digressions. Plot rundown is usually the least engaging part of a piece of movie criticism—it can feel like the most obligatory. Did you find it difficult to inject energy into summary?

Whenever anyone tries to sell me on a novel or persuade me to go to a film, they start summarizing the plot. Within a sentence, I’ve tuned out. So, I like the irony that I’ve written these two books about film where that’s what I’ve done. I’ve summarized the plot. On the one hand, I feel, as a novelist, that I’ve been hampered by my inability to think of plot. Other things have had to step in and do the work that is often done by plot: structure, for example. Stalker has a plot that can be summarized in three lines, while Where Eagles Dare would take a lot more explanation. But since the plots—whatever their degree of complexity—are preexisting, I’m free to do the stylistic stuff. In terms of tone, I hope I’ve increasingly become a comic writer. I’ve become fond of the multiple punchline—several gags in one sentence. The fun of the book for me is in the style and the tone, which I hope is screamingly funny.

I enjoyed how you playfully—but not at all mockingly—point out movie fakery. Like in this line about a scene of Eastwood climbing a rope: “Eastwood abseils down it with that longlimbed easy elegance that could only be his (i.e., his stunt double, Eddie Powell).” It’s this charming juxtaposition of acknowledging Eastwood’s magnetism while admitting, in the same breath, that it’s not him pulling off these feats.

I like making a serious point and then undercutting it with a joke, and then going back to a serious point. Maybe more than that, I like to do both simultaneously, whereby you’re making a serious point as a joke.

Your amusing observations are occasionally interrupted by citations of serious books on the toll of battle: Martha Gellhorn’s The Face of War, Dave Grossman’s On Killing. What were you trying to achieve with these sudden intrusions of real-world carnage?

I’m very interested in the Second World War and I love reading military history. But my interest in the war has its origins in films like this, because of the age I am. My childhood was steeped in the Second World War, but it was a war in which—to put it glibly—there was no Holocaust, there was no Stalingrad. It was this Second World War of films like this and of comics. I became conscious of Stalingrad and the other horrors later through an amazing series, The World at War—as did many kids of my generation. So the serious stuff about the Second World War and my knowledge of it coexists with these Mission: Implausible–type films. That was key: To find a way to move easily from a jokey thing to quoting Svetlana Alexievich, a writer who said that, for her, the most important unit of information is suffering. So you need the right tone that makes the two things sit comfortably alongside each other. The film is really an excuse for what’s going on stylistically. It’s a MacGuffin for me to get into the thought and comedy of writing.