Emma Grove opens her graphic memoir, The Third Person, with a therapy session already underway. We don’t know anything about the therapist’s intentions or the patient’s reliability or even her hold on reality, but something definitely seems off. The rest of the doorstopper memoir about Grove’s life as a trans woman with dissociative identity disorder (complete with “alters,” or distinct personalities) unfolds similarly—as a transfixing psychological puzzle. Grove’s candor adds to the intrigue. She states up front that she doesn’t embellish her recollections: “As much of this as possible has been retained to give an entirely accurate account of exactly what was said. No dialogue has been invented or tailored to suit the author’s point of view or for storytelling purposes.” The effect is that we trust and empathize with the author as she illustrates the traumatic disintegration and hard-won reintegration of a fascinating mind. Grove and I talked recently via email about her debut.

KAREN SCHECHNER: With the majority of your memoir set in a therapist’s office, you reveal so much about yourself (and “Toby,” your therapist). Did you have any hesitation about that level of exposure?

EMMA GROVE: It’s always scary being that self-revelatory. I was scared for a long time about that, but then just figured I’d roll the dice and see what happens.

The whole inspiration for the book was, What if I put everything I’m deeply ashamed about myself on the page for everyone to see? My thinking was that maybe I’d come to realize that I wasn’t as bad a person as I thought.

One thing I said to myself during its creation is, “If it’s something you don’t want to write about, and something you’re deeply ashamed about, in it goes.” If there was something I didn’t want to put in the book, it was a good indicator that it had to go in.

Just as I didn’t flinch in including episodes showing me at my worst, I really tried to highlight moments showing “Toby” at his best, and moments that really showed his caring, nurturing, compassionate side. I really didn’t want to paint him as a villain or show him as being one-dimensional.

I was emboldened by other writers/graphic novelists who were just as brutally honest about themselves in their work, like Jennifer Finney Boylan, Ellen Forney, Alison Bechdel, and Rachel Lindsay. I figured, if they could be that brave, maybe I could, too.

There was obviously some very bad therapy happening. Was it helpful to portray and reframe that experience?

Me seeking to have a positive, profound relationship with a therapist, and hoping he would help me on my journey through the next stage of my life, and having it go the way it did, definitely left me shattered. I felt completely lost afterwards, like I had nowhere to turn to. The sessions themselves made me feel completely powerless, unable to make any decisions for myself, as I was “sick.”

Writing the book helped me, finally, after thirteen years, to take back that power. It helped me to piece together what happened, find some clarity and understanding in the chaos and confusion, and finally move on and put it behind me.

The book is dedicated to Katina. Will you talk about who she is/was and why you dedicated your book to her?

When you have dissociative identity disorder, your relationship with your alter is actually very profound and very real, and they become very real people. Me dedicating the book to her was my way of honoring her memory. She was never more alive than she was in those therapy sessions you see in the book.

It was through writing this book that I realized all that Katina had done for me, what she had meant to me. At one point I thought of just naming the book Katina and having it be all about her. She was, really, my constant companion, even though most of the time I had no memory of what she was up to. She was like having a best friend and close sister all rolled into one.

Whether she was “real” or not is something I can’t say definitively. She was real to me, and became a very real person for the therapist “Toby.” Writing the book made me miss her all over again. I still cry just thinking about her.

The Third Person is a 920-page, nonchronological tale with multiple, complex developments—but it all fits together so neatly. Why did you decide to structure your story as a “gigantic jigsaw puzzle,” and how did you keep everything so well organized?

The book was originally 1,200 pages, literally three feet tall. Editing it, in total, took six months, trying to shape it into something resembling a cohesive narrative. The therapy chapters were mostly chronological, and needed the least editing, but Book Three, the third part, was an editing nightmare.

I’m a big believer that you have to create a mess before you create order. For example, in reorganizing a room, throwing everything into a heap in the center of the room and then slowly putting everything in its proper place. So, I had an enormous stack of papers I needed to find some sense of order in. That said, I still wanted the book to convey the fragmentation and confusion associated with DID, like puzzle pieces the reader has to put together. I wanted to push it further, but it would have made the book too confusing to read.

A graphic memoir’s illustrations can convey, at a glance, multiple storytelling elements (setting, character, tone, mood, etc.). It’s so much more efficient than prose! How does drawing shape your storytelling?

While seeing the last therapist you see in the book, I actually wrote a 250-odd-page memoir that I didn’t even try to get published. The only drawings were drawings that I had done at this or that specific time in my life, like when I worked at an animation studio and took figure drawing classes in LA. What I find fascinating now is that it was written by me, Emma. All of the episodes you see with Katina in The Third Person are just not there in that book.

For The Third Person, I hashed out the whole thing in really rough, simple sketches, done as quickly and spontaneously as possible so that I could get it down on paper before I forgot it, and roughed them out as I was remembering everything. It unlocked the subconscious part of my brain, and allowed me to remember things as vividly as if they had happened yesterday, even though most of the events took place over a decade ago. It was the only way I was able to recall the moments you see with Katina.

Hair reveals a lot in your memoir. You use it to mark trans identity, to distinguish between Emma and Katrina, to show changes in mood or character development.

I’m still obsessed with hair. It’s definitely a big part of my identity, which I think is true for a lot of women.

There’s a chapter in the book where, at age sixteen, I had long, thick, beautiful hair. At the start of the chapter, I’m proud of it and defend it. By the end of the chapter, I go to a hair salon and get it all cut off. It was definitely symbolic of me giving up on having my own identity, and acquiescing to whatever and whoever anyone else thought I should be. Me, then, years later, setting up a P.O. box so I could mail order wigs, without my family knowing, was me secretly, privately trying to regain my sense of self.

Your visual representation of anger is very effective. In one scene, the abusive grandfather morphs into something like a fanged shadow, spreading across the page. Was it a challenge to develop a visual language that not only shows the escalation of anger, but also its effects on its target?

I had an art professor who once told us that if you use black in your work, you should use it as a color, to define shape or represent something, not just to fill in space and create a void where you don’t know what else to put there. So, in my book, the color black was definitely symbolic of many things, but mostly abuse. Abusive people, in the book, are all eventually represented as black silhouettes.

So much of the book is about the aftereffects of abusing someone. Book One and Book Two show the aftereffects of trauma and abuse. Book Three shows its origins.

The whole book could be seen as a call out to not abuse other people, especially children, and just how badly abuse and trauma in childhood can affect you in adulthood.

Your portrayal of dissociative identity disorder seems less like Sybil and more like a heightened version of something more common—a compartmentalization of the self. While DID is relatively rare, and a response to extreme trauma, you dramatize your experience of it in a way that enables the reader to relate to and understand it.

Trying to show people, visually, what DID felt like was definitely a challenge. I was lucky in some instances, as in some scenes that show me or Katina driving my car while me, Katina or Ed are in the back seat. That dialogue actually did happen in my car, but was also a good visual metaphor for who was “in the driver’s seat” at that moment.

One thing I did that was a slight artistic license was showing, visually, my other two “parts” talking to me, separately or together. It just made everything more understandable, even though I couldn’t actually SEE them next to me.

Me talking to them, either in my mind or as imaginary entities sitting next to me, was definitely not made up, though. I talked to them, either internally or as quietly as possible out loud, all the time. There’s a scene in the book where Ed and Katina are sitting next to me on my futon, and I talk to them and reach out and pat their knees. I really did that in real life. I couldn’t see them, but I could feel their presence enough to pretend to, and almost feel like I did touch them.

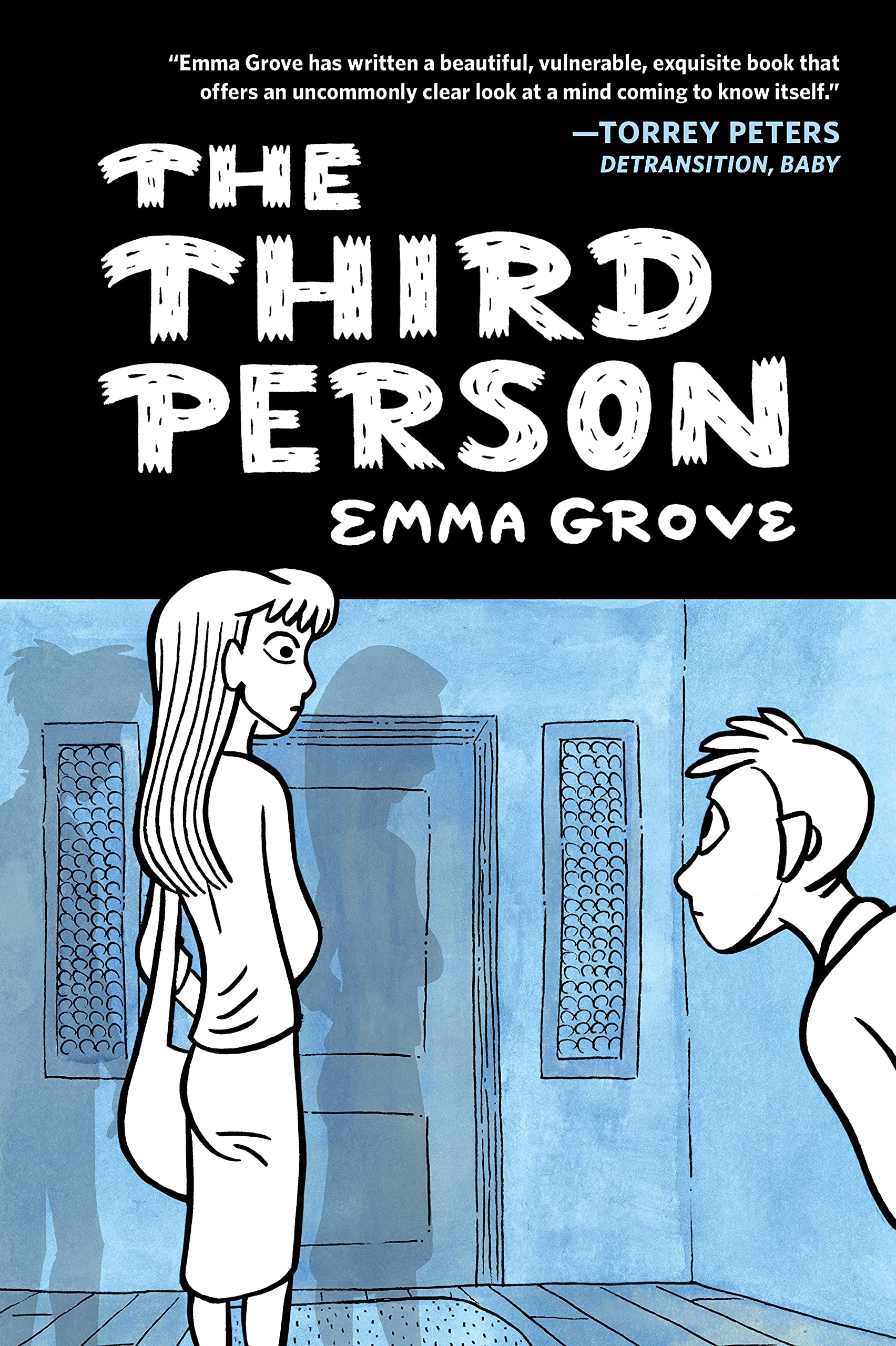

The ONLY time I actually SAW something was in a chapter close to the end of the book, where you see Katina get up from sitting beside me and walk across the room and through a darkened doorway. In that moment, I actually saw a shadowy form of a person walking across the room. If you see the cover of the book, the image of the “shadow people” standing on either side of Katina is eerily similar to what I saw that day.

A figment of a warped, overactive imagination, or something else? Who can say . . .

Trans identity and DID seem as important to the story as the understanding and integration of a fragmented core.

Getting in touch with my “core self” was me getting back to who I was before the abuse, before the “splitting” and fragmentation took place, and who I would have most likely developed into had the trauma and external pressures—and striving so hard to be what others wanted me to be—not forced me to lose all sense of self.

For me, coming to grips with having DID and being transgender were a solution to a problem. If you have DID, you find ways to amalgamate and integrate the disparate parts of yourself so that you can one day live as a whole, complete person. If you’re transgender, you find a way to transition to where you can live and be at peace with yourself and the world at large, and comfortable with yourself so that you can be comfortable interacting with others.

So, yes, they’re all part and parcel, because they all clue into identity.

Karen Schechner is a writer and editor in South Salem, NY.