Depressed as a teenager in London, Helen Oyeyemi wrote a novel instead of studying for her A-level exams, had it published at the age of twenty, and headed off to Cambridge, where she wrote two plays. Oyeyemi then spent her twenties writing four more novels and traveling the world before settling in Prague, a city with which she felt a mysterious affinity—she sensed there the potential for fantastical happenings.

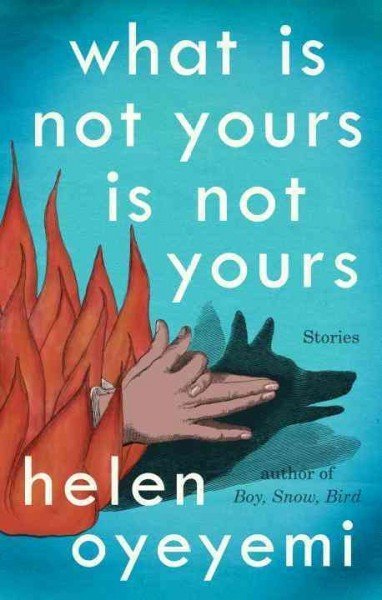

In her seventh book and first collection of short stories, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, Oyeyemi stretches the bounds of fiction with fairytale-like parables that contain more locks than there are keys, and are set in peculiar lands where puppets speak, roses commit murders, and the Big Bad Wolf can be bargained with. In the carefully tangled universes of What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, every haunting image, plummeting mood, and perverse custom is so precisely wrought that there’s no reason to believe that the spirits Oyeyemi wrangles are not real. Any sense of stability you might find in the collection’s seemingly forthright title is just another illusion. Recently, Oyeyemi and I met at the Bookforum offices in Manhattan to talk about fairytales, MFA programs, and breaking the rules.

Your last book, Boy Snow Bird, was a sort of retelling of Snow White, but much darker, as if you wanted to restore the darkness that Disney bleaches from fairytales.

I loved Disney as a child—it has a faith in storytelling that I try to retrieve as a writer. But it’s hard to reach the conclusions that Disney does. I write and retell fairy tales because I’m convinced they are real, that they are talking about our lives as we live them. Not idealized or fantastic. They are talking about truths that we sometimes want to look away from. And when you move a fairy tale to the 1950s, or the 1930s, as I did with Mr. Fox, and you change the language and the register of it—it’s not quite a trick, but it’s a way of diverting the reader and catching them in a trap.

By making it familiar to us.

Right. You’re lulled by the fact that it sounds so everyday. I’m trying to transmit my reading of the fairy tale—as a truth—to bring readers into that conception of it as well. Because I’ve never read Snow White and not been horrified by it.

You mentioned a faith in stories. What does that mean for you?

Especially in our era, it’s become really hard to find meaning. Because there’s a multiplicity of meaning in any simple story that we’re told. There is a great temptation to move toward alienation and nihilism and just say, “Nothing means anything.” I think a faith in stories is an assertion that anything that happens to you does have meaning.

Reading your stories, I’d often get to the end and think, “It’s over?” And then I’d have to go back and piece together actions that I’d initially thought had no consequences, or weren’t related to other strands of the plot.

I’ve been rereading One Thousand and One Nights. Every story revolves around another story. It’s never-ending. It’s just this engine of meaning, and One Thousand and One Nights always makes me feel like wonderful things can happen to me.

Is it important for you to balance darkness and horror with these simple desires or pleasures?

I’m content to have them coexist. I used to feel quite embarrassed and ashamed by my desire to be happy. But I feel there’s nothing I can do about that desire, and if I try to cover it up, I feel a sense of dishonesty that I don’t like. I think I’m so much in my head that I get surprised by emotions, and they seem to creep up on me, like, “Oh, I should put this in.”

What influences and traditions would you say you’re in conversation with when you write?

I feel that I write two different kinds of books. There are the duty books—books I just felt I had to write. With Boy Snow Bird, I thought, “This is my wicked-stepmother story, this is my angle on that.” And it’s a reading of Snow White that addresses, dead-on, Snow White’s whiteness as the source of her beauty. With White is for Witching, I had to tell my haunted-house story.

Then there are the books that are like games. Mr. Fox and What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours fit in there. And I think those are the ones that I love—the ones I think are useless and not contributing anything. Because of that desire to be happy, and that desire to play, but also, they feel like my own, and not just projects. These are the books where I feel I’m developing toward something, some style. And then I can tell a story that isn’t even a retelling but is my own thing. I’m curious to see what that will be like when I get there.

Sometimes your nonwhite characters are at the center of a story, sometimes they’re more peripheral. Some are protagonists, some antagonists. It doesn’t seem as if you were bearing the burden of representation as you wrote. At the same time, you do make note of the characters’ races.

It’s a visual marker for me, just a way of describing what someone looks like. But, for instance, in the story “Sorry Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea,” Anton doesn’t mention that he’s black because it felt like Anton would not—he genuinely doesn’t care. In that story, if I found myself using race to describe how someone looks, I had to delete it.

From my perspective, part of the fun of What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours was building this new Europe. It’s populated by the people I see. I see all of these people, and that’s why I’m suspicious of books that are set in big cities, but in very homogenous societies, where there are no nonwhite people there except for, like, a server at the table, or something. I’m like, “Um. . . . ” Because it’s just not like that. If you’re writing a book that’s set in the present day, that’s impossible.

And the people of color interact without white people, which is nice to read. It’s not a cast of white people and one black person.

I hate when that happens! The black best friend.

You write from the perspective of a lot of different kinds of characters: a child, a man, a woman . . .

A puppet! Writing about keys led me to puppets—trying to write from the perspective of something that is inanimate unless moved. It makes you start to think about the life of objects. Whether they can be alive even though they never exhibit any signs of life, and what they witness, and how they come to reflect the personality of the person who spends time around them. The puppet Geppetta’s was probably the most simultaneously thrilling and scary perspective I wrote from in the book.

A lot of the stories take place in these altered worlds, where there are rules, but they’re not our rules. A story would seem like it was taking place in some distant land, long ago, but then you’d put in a little detail that seemed anachronistic—like a viral YouTube video or something. And it jumped out to me because we’re taught that that’s such a no-no, that we’re supposed to try and make literature timeless.

Nothing is timeless. There’s that Borges line about how writing should affirm the hallucinatory nature of reality. I think that is true. Everything around is constructed, and sometimes these temporal markers—YouTube, Kim Kardashian—help us as readers get more grounded.

Is the class you teach at Kentucky a workshop?

No. I think it was supposed to be, but I have this absolute horror of workshops. That’s why I dropped out of my MFA because I couldn’t, I can’t. Instead I just send them passages to read and we talk about the passages and what they do and why they work.

What kind of stuff do you have them read?

My class is based on Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium. He talks about the qualities of writing that he thinks will move fiction forward: lightness, quickness, multiplicity, exactitude. And the sixth one he didn’t get to write—he died before he could write it. The sixth one is up to you. That’s how I’m going to end the class. So we’ve been reading Ali Smith, we’ve been reading Heather O’Neill, Han Kang. Some Borges. I’ve been doing a lot of fabulism with them.

How conscious you are of breaking certain rules when you write?

Sometimes I wince a little bit, because I think of how annoyed my hypothetical reader will get with me, but then I try to give them a treat for going a little bit further. Reading other writers who break those rules like crazy and are really good gives me so much courage and confidence. Ali Smith wrote this book Hotel World. A girl dies in the beginning. And the death is the beginning of the story, it’s not the end. I was like, “People can write like this?” Barbara Comyns, as well. She’s almost painfully candid about the process of writing the book. She’ll have narrators who complain, “I’m on page 12, and I can’t believe I haven’t said anything yet.” And there’s something about that wide openness that makes me feel like, “Oh, I can get away with this.”

The signature theme of What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is that of keys and locks. And sometimes, when a character tries to turn a particular key, it’s a huge catastrophe.

I think that there’s an ambivalence to the title . . . a sadness that comes with desire. The sadness that the things I want, some of them—probably most of them—I can never have. There can also be glee and relief in that, because there are so many problems associated with ownership, and nothing ever stays in our possession. Sometimes the way that you use lose the things you had is painful, and can be the breaking of you.

Heather Akumiah is a writer living in New York.