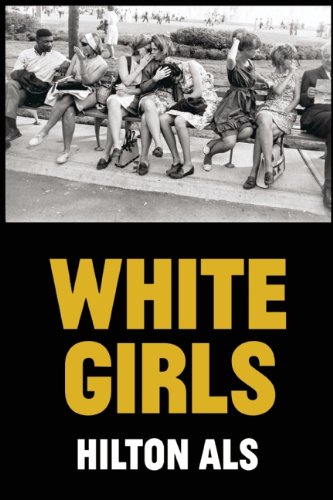

It’s been 15 years since the publication of Hilton Als’s previous essay collection, The Women. Now, in the florid White Girls, the New Yorker writer expounds on topics as varied as Truman Capote, Louise Brooks, Gone With the Wind, and Eminem. Effortlessly controversial, Als manages to add new layers to familiar subjects (the “n-word,” Richard Pryor, Flannery O’Connor) and fearlessly challenges conventions of race, culture, and sexuality. Bookforum recently called the author to ask him about White Girls.

BOOKFORUM: You call a lot of people “white girls” in your new book, including Louise Brooks and Flannery O’Connor, which makes sense, but you also call Malcolm X a white girl [or at least the back cover of the book’s galley does]. How do you define “white girl”?

HILTON ALS: Oh, I don’t define him as a white girl; I’m talking about his mother. In his book, he talks about her race—because she was mixed-race—he talks about it quite a bit, and says that she appears white. And I think that has a big effect on him in terms of his feelings of difference. He definitely was all about his mother being a white girl.

By writing about people like Michael Jackson and Malcolm X in this sort of irreverent way, do you worry that you’re going to be accused of going after some of the black community’s most sacred cows?

Well, every society has its sacred cows, and I don’t see why black people should be exempt from their cows being looked at critically.

Malcolm X also appears in your first collection The Women. What about him is so fascinating for you?

I really loved his book because it was so melodramatic, and I also think that he was really attractive. I think that he did something that was very different from my mother’s generation, which really revered Martin Luther King Jr. My sister’s generation was much more black nationalist, and he was a big hero there. So I think that the influence trickled down to me from my sisters, who were older and who had much more direct access to the black nationalist movement of the ’70s, which was always interesting to me.

I sort of feel like Jamaica Kincaid is the Sasquatch of Caribbean writing…

I love that word. What does that word mean?

I feel like she’s just so big that she just sort of like sucks all the attention away from other Caribbean writers. And I’m from Antigua, so when I write about Antigua, I almost hear her voice in my head. Is Jamaica Kincaid an influence on you?

Oh sure, I love her. She’s a friend of mine. As a reader, would you say that she’s critiquing Caribbean culture more than anything else? I think she gave me the freedom to do that. I think in The Women I talked about her a bit, right? I think that she definitely plays a part in my understanding of how to look at one’s own particular culture, for sure.

In The Women there was a passage that I kind of thought had a little bit of Jamaica Kincaid-ishness to it.

Oh, yeah, I think that was the passage where I quote her. [Laughs] That would make sense, Gee, since I’m quoting her.

This is a weird question, and I’m not even sure what I mean by it, but what does it mean for you to be a Caribbean author living in America?

Oh, I don’t think I’m Caribbean at all, because I think you would have to have been born there. My descendants come from there, and it created a sense of societal difference. Within black culture—American black culture—there are lots of ways in which blackness gets kind of one coating and one experience, and so I’m grateful to my family for giving me a different kind of experience. I think it sets you apart, allows you to look at things in a different way.

The first essay in White Girls is so confounding. I found it deliberately oblique, almost as though you were writing about people who you honestly didn’t want the reader to fully know. Would you say that that essay written more for you than your reader?

Gee, you’ve been throwing out some pretty powerful statements without actually explaining them!

[Laughs] I’m sorry!

Well, oblique in what way? I mean, what would you like to know about those people?

Well, the woman towards the end of the essay you call Mrs. Vreeland—it seems like you call her that to confuse the reader into thinking you’re talking about Diana Vreeland.

No, I say in the section, that she was stylish like Mrs. Vreeland, and it was a nickname that I gave her. I called her Mrs. Vreeland for a reason. She was a very significant person in my life who died, just as the story tells it. I think that people have a right to their own lives, so whatever I fictionalized in that piece was actually in service of the story, less that I wanted to hide, but in service of the story. But I’m curious about your sense that it’s oblique because other people have been saying that it’s not that at all. I’m just curious about why you feel that way.

Um, I don’t know. It might be a thing with your style of writing, which I love. You do a lot of riffing and it does—I mean it’s powerful—but it is a little bit confusing. So I’m not entirely sure why I found it oblique, but I was angry by the end of the essay. For some reason, that essay in particular made me mad. [Laughs]

Mad at the author or at the subject?

At the author, yeah. But then I read on in the book, and I just fell in love with it.

Oh, I’m so glad. Well, the thing that happens in the first essay is that it sets up everything that you’re reading afterward. Every person or idea that comes later in the book happens in the first essay. So there might be in a weird way too much information in the first part. But I wanted it to be—you know how you have something wonderful like Go Down, Moses, or Naipaul’s A Way in the World where they’re sort of inter-connected stories that make a book? I didn’t want to do a typical collection, I wanted to do a book that was based around this idea of it all being one story. So I guess it’s all one story about a sensibility, and I don’t think that anybody loves any sensibility completely. I don’t mind you being irritated by it at all. But you’ll have to explain to me one day when we meet what you mean.

Yeah, I’m planning on coming to one of your events in the city. So who is the audience, I wonder, for this collection?

I don’t know, what do you think? I’m just hoping that people find things in it that they like, and I hope that I’m saying something that means something to people. The biggest hope you can have is to really communicate something of your experience to the world. So maybe people will like it, I don’t know. Or be irritated by it, which is good, too.

I know that most of the essays are nonfiction, but a few of them seemed more like fiction, including the piece depicting Richard Pryor’s sister as a voiceover actress in porn.

That’s a complete fiction, yeah.

So when you have a topic, how do you decide which treatment you’re going to give it—fiction or nonfiction or a blend of both?

Well, Richard doesn’t even have a sister. But I wanted to say something about the nature of fame. And I also have a great friend whose voice I really love as a speaker, and I wanted to try to figure out how to make her voice take the form of someone telling a story. So it seemed very natural to write that in a fictional voice. There’s fiction in the first piece, and then I think those were the largest sort of fictional pieces in the book. But I think that the story tells me what to do, I don’t really tell the story what to do.

You describe yourself in the book as being friends with Andre Leon Talley, but your essay on him, which was hilarious, seems like a little bit of a takedown, a “read” of sorts.

I really love him. That piece was something that he liked initially, and then other people didn’t like it and so he didn’t like it, and then I was just really sad. Because I didn’t feel that it was a takedown, I felt that I was really describing a world that wasn’t as good as he was. I didn’t find any of the people associated with him at that time in Paris to be worth … I mean, they just didn’t have a degree of his intelligence or elegance of spirit. And so I thought I was really describing … that, and not doing a portrait of someone to take them down. I thought I was doing a portrait of someone to show that I didn’t like the world he was in.

Yeah, the part at the end where the woman…

LouLou de la Falaise.

…that was shocking to me.

But I think there’s a lot of that kind of bullshit…

In fashion?

Fashion, the art world, anything that is defined by a-historicism. You know? A-historicism means that people just say shit all the time, and then they don’t really back it up with anything. I think that Andre—it’s like actors who are sometimes too smart to be actors. Well, Andre’s too smart to be in fashion, but he is, so that’s really what the piece is about. How does an intelligent person with a really great sense of history live in a world that’s defined by moments? He’s an amazing person and I love him. I’m sorry he can’t love me back, but … [Laughs]

Does being friends with your subjects alter how you write about them?

I’m not really friends with them when I’m writing about them. Sometimes it can happen that I’m friendly with them after the fact, but never really before.

Andre is one of the few black figures to have clawed his way into the rarefied world of fashion, culture, and power. Do you feel like you’ve done something similar in the literary world, or at The New Yorker?

Well, I don’t really have any claws, and Andre doesn’t have any claws either. I think that I’ve just worked hard and maybe what I have to say is of value in that world, I don’t know. That’s a question for editors, I think. I never know what to say as a writer or as an artist in terms of my own value. But I hope that I have contributed something to that world, that publication. I hope so.

So, will we have to wait another 15 years for your next book?

Nah. I think that it took awhile because I think when you come from no place and then you have a book, and then your life becomes different, I think that it takes a while for you to catch up to your life. And I feel really sort of prepared now to write books.

Gee Henry is a freelance writer who lives in Manhattan.

Related Article: Melissa Anderson’s review of Hilton Als’s White Girls