“It feels like we’re living in hell,” James Greer tells me. A heavy sentiment, to be sure, especially when dropped into an otherwise sunny afternoon, on the back patio of a combination coffee shop/surf shop in New York’s Lower East Side. But Greer has spent a lot of time lately delving into climate-change research—for a film project—so the doomsday vibe is understandable. And despite the looming environmental apocalypse, he’s still got faith in the power of words to inspire and provoke.

Everyone’s a multi-hyphenate these days, but Greer actually earns the distinction: novelist (this is his third; his debut was championed and published by Dennis Cooper); musician (mid-’90s bass player for Guided by Voices, most famously); screenwriter (Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane, along with what seems like several dozen other projects in various stages of completion and production); and now director (Greer is shopping his debut feature—Mirror Moves, about the unwitting wife of a serial killer—on the festival circuit).

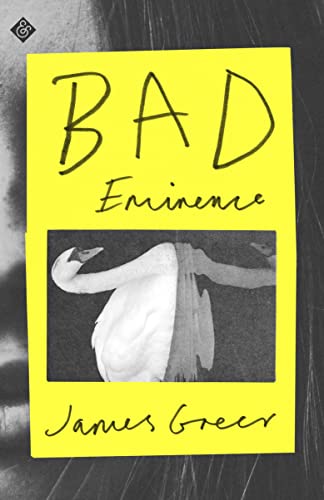

His latest novel, Bad Eminence, is an erudite romp that is both confounding and entertaining. It borrows liberally from a 1984 novel by Alain Robbe-Grillet, Recollections of the Golden Triangle, and sets off on a wild ride through suicide, the photography of Francesca Woodman, demonic infestation, gilets jaunes protestors, and tragic twins. There’s also a Michel Houellebecq–esque miscreant who, we discover, might just be an actor impersonating a real author. Confused yet? Best to just let it all wash over you.

SCOTT INDRISEK: I’ve got a unique perspective on your novel: I read Bad Eminence, then read Robbe-Grillet’s Recollections of the Golden Triangle for the first time—and then read your novel again. I was a bit nervous before our meeting, since it’s very easy to have the two books meld together in the mind.

JAMES GREER: I wanted Bad Eminence to work whether you’d read the Robbe-Grillet book or not. If you have read the book, there’ll be another level of meaning.

The original idea for the book came from a friend who had gone to high school with the actress Eva Green. She told me—I’ve never checked on this story—but she told me that Eva Green has a twin sister. And that in high school, everyone thought the twin sister was going to be the big actress and movie star, because she was much more outgoing and exhibitionist, whereas Eva was bookish and shy.

That was just the initial seed: What if you had a twin and you thought that she stole your life? Other threads wove into that. I read Recollections of the Golden Triangle and thought: This could work as well.

Then I had the idea of Michel Houellebecq not actually being Houellebecq. Twinning the twin theme. Houellebecq is so perfectly a caricature—he looks exactly the way his personality should be. I thought: “Wouldn’t it be funny if, if he really was this sort of well-groomed French businessman of the type that I know very well? And he’d hired this totally innocent misanthropic, cigarette-smoking asshole to impersonate him, to do all the public stuff, while he wrote the books?”

I’ve always hated doing book readings and publicity of any kind—

Like this?

Interviews like this, fine. But public readings. And the necessity to be on social media, which I’m not. In the past, I’ve actually had friends of mine—actors—go out and pretend to be me at readings.

I don’t go to book readings. I don’t know who goes to book readings. I don’t understand the point of book readings. First of all, Bad Eminence is narrated by a twenty-nine-year-old British/French woman. Me reading it? That would be weird. I’m not going to do a funny accent.

Did writing from that POV give you pause?

I didn’t think twice about it, and that’s partly because of working in film. You’re always writing for people who are “not you”—always. And almost everything I write with [co-screenwriter] Jonathan Bernstein has a strong female lead.

In some ways, Bad Eminence is a “translation” of Recollections Of the Golden Triangle . . .

His book is far crazier than my book—the narrator turns into a different person. It makes zero sense. This makes a little bit of sense. His book is a narrative about narrative, and I love that kind of thing.

I guess, you could say, Bad Eminence is my attempt to do that in English. But more natively, in a contemporary version that makes sense to me. Taking what I like about that and applying it to this.

Unless you’re a well-known person like Lydia Davis, or someone who’s doing a new Flaubert or Proust, they don’t really talk about the translator that much. That was interesting to me.

All these ideas were circulating. And then there’s the idea of Robbe-Grillet being a member of this very loose collective, or school, or whatever you want to call it, I think he wrote a manifesto—For a New Novel. Which I always think is funny, like Dogme 95. As a formal exercise, that can be fun. It doesn’t seem that the thing we need now is more rules. But I don’t give myself rules.

At the time, Robbe-Grillet was trying to figure out how to do something new with the novel. Post-Ulysses, that’s stumped a lot of people. It’s not very fashionable at the moment, but that’s still the kind of thing I like to do—be playful, have fun. When I’m writing movies, there’s a form, I have to tell a story. But with a novel I’m going to write something that’s more or less purely for myself—or at least, the initial impulse is for myself, and then hopefully other people will like it, too.

Drawing on this sort of thing engages me more than if I were to just tell another story. And I draw on a lot of novels. I mean, I’ll read anything—a lot of stuff that’s just straight narrative.

Genre fiction?

I love detective novels, if they’re well done. In science fiction, there’s tons of interesting stuff. I’ll read Jonathan Franzen if I have to. He’s really good at what he does, but it just wouldn’t engage my interest to try to do something like that. He’s engaged in a different project than I am. He’s a storyteller. I’m just playing with words.

Is the playfulness purely on the level of language—wordplay and puns?

That’s certainly part of it. But it’s not all of it, because—not to reference Joyce again—Finnegans Wake was kind of the end point of just playing with words.

There has to be something there for the reader—also for me, yes. Another aspect of this is I’d done a lot of research for this climate-change-disaster script that I wrote. Very depressing. Very scary. Very dismal. Everybody I talked to said that we’re fucked, way past the point of no return. It’s definitely gonna get really bad.

Part of Bad Eminence was writing my way out of despair. You know, just like, “There is no future, there is no hope.”

Satire to me is a lesson, you know, whereas parody is a game. And Bad Eminence is more like a game to me. It’s not “Let’s have fun while the world is burning,” but it’s trying to find some way forward, some shred of hope to hang on to. The book is a project to try to do. I’m not sure that it achieves it, because I’m still not hopeful.

The object of anything that I write is aiming at a kind of transcendence. I’m an atheist, so I don’t have that. There is some sort of transcendence available in art, but I don’t really know how it works, or how it would work. Maybe this is one version of how it would look, of what it might look like.

Can we talk about the book’s cover? Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but it seemed to go back to the idea of “translation”—photocopies of photocopies of photocopies . . .

You can’t read too much into this. That’s what I like about it. I like it when people try to read more into it than I actually intended.

There are jokes in Bad Eminence that only I can possibly get. Literally private jokes. They’re not important to the story—that joke is funny to me, and only me, for reasons that I have probably forgotten by this time. Everything has its mirror reflection, its link to something else, somehow.

And that’s the whole idea behind “everything is connected,” that gets into the more woo-woo, transcendental thing: until human beings realize that everything literally is connected, we’ll never dig ourselves out of this hole that we’ve dug.

Could you ever see making a film out of Bad Eminence?

No. It’s unfilmable. I mean, if I’ve done my job, it’s unfilmable. There’s obviously a way to do it—but why would I? Why would anyone start with that?

You co-wrote the script for Steven Soderbergh’s Unsane, which he famously filmed using modified iPhone 7s.

We would shoot a crazy amount of pages—because you could, because it didn’t take time to set the camera or lights or anything. And then he’d go back to the hotel and start editing. It’s 2 or 3 in the morning, and you’d get a call: “Want to see the edit?”

I was one of the few people that would show up. He was always trying to get people to stay up that late. It’s like, “Dude, we gotta be back on set on 8 am.” He doesn’t drink coffee. He’s drinking his Singani. He’ll drink and he doesn’t ever seem to get drunk.

I was exhausted even trying to keep up and not having to do anything. Being the writer on set is one of the most boring things.

Is it common for the writer to be there?

It’s not as common as it should be. But it’s common with [Soderbergh]. He likes to have the writer on set in case there are issues.

And it can be tedious—because you’re not, you know, you’re not doing anything. There’s not a lot of fun to be had there. But I was also trying to learn, watching him. Obviously he is operating at a much higher level than I could, but at least he’s using equipment that I can understand.

For him, the phone is a capture device. He can do things that he just couldn’t do with a “real” camera.

Georges Perec comes up in Bad Eminence—a French writer who once completed an entire novel without using the letter “e.” It’s a whole school of writing that’s about getting something creative out of setting limitations. Is shooting a movie with an iPhone like that—a productive pain in the ass?

Steven explained that it was as close to using a pencil as a camera could come for him. It was just another tool he could add to his box.

At one point in the novel the narrator, Vanessa, says, “Because this book will have a beginning and an end, in order for it to succeed the reader will have had to read every preceding book and every subsequent book.” I love how the novel exists in this web of other stuff, like the Robbe-Grillet novel, but also an album by the band Death Hags, which is an official “soundtrack” to your book.

It would be great if everybody reading this book has read all the same books I’ve read. But even if they haven’t, if I reference them, at least then maybe they’ll go check out these other great books which tie in, even if it’s in a tenuous way.

What’s your personal connection to France?

I spent a lot of time there. I lived there for a while, in the middle of nowhere, off and on for a few years. New Wave French film was one of my earliest and biggest influences, Godard in particular.

I started studying French in high school, just because you had to pick a language. And then I just really stuck with it. I guess I’m a Francophile.

I spent a lot of time going back, and when I was touring—when Guided by Voices played France, or the Breeders, or Pixies. I like France in general: the culture, the food, the wines, all these things. It took me a long time to get to the point where I felt comfortable enough in French. I also consulted for this French videogame company, Ubisoft, on their movies. They made Assassin’s Creed, which was a huge failure.

The stereotypical image I have of some French literature—including, say, Georges Bataille—is a lot of visceral, disgusting sex and violence . . . but for a philosophical purpose!

That was Robbe-Grillet’s excuse. He’d give interviews where he’d say, “If I write it or make a movie about horrible things, that means I won’t do those things.” OK, I guess that’s one way of justifying it. I’ve read like three of Robbe-Grillet’s books. I tend to prefer Nathalie Sarraute or Marguerite Duras. But Robbe-Grillet was so ripe for caricature. The throughlines of that stereotype that goes back to Bataille or Céline, people who revel in the gutter: nostalgie de la boue.

I kept wishing Bad Eminence was hypertext, so I could just click on references and have them explained. But you do summarize some of the important things in an appendix that you call the “Help Desk.”

That was a late addition. Jeremy Davies [my editor] was like, “Maybe you should tell people what the nouveau roman is?” I didn’t want to slow down the text with definition.

It’s called the “Help Desk” and it’s completely unhelpful. There’s some real information, and then there’s some . . . poetry, or whatever. I can’t help myself.

My next thing that I want to do is a detective novel, but I’m sure I’ll manage to fuck it up. A murder mystery set in the early-’90s in New York City. I want to get the details right—I was there, but mostly . . . drunk. It’s set in the L.E.S., specifically the bar 7B, which used to be a place that everyone went.

I’m just sure, while I’m writing, I’ll be like, “What if? What if everyone in New York was a ghost?” I’m hoping not to. This’ll be my fourth novel, and I would like one to just be a straightforward narrative.

Scott Indrisek used to work in the art world, and he’s pretty happy that this is no longer the case. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.