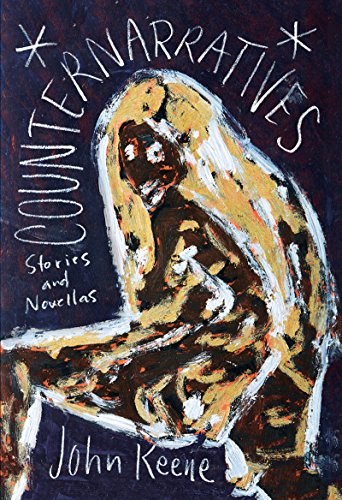

The writer, translator, and poet John Keene has long married a daringly experimental style with a commitment to stories that are usually omitted by history’s ellipses. It’s an approach tangible in his work as a translator, where Keene has long expounded the need for English editions of black diasporic authors (coining, in his essay “Translating Poetry, Translating Blackness,” the hashtag #NonAnglophoneNarrativesStoriesPoemsandOtherFormsofExpressionofBlackLivesMatter); as well as in his fiction, from his 1995 debut Annotations, a black, queer bildungsroman-turned-fugue of semi-autobiographical notations, to Counternarratives, a collection of short stories and novellas published in 2015. A feat of decolonial historiography, Counternarratives utilizes a wide array of historical idioms to explore the experiences of people of color in the Americas from the seventeenth century to the present. Keene, who is a professor and the chair of African American and African Studies at Rutgers University-Newark, was recently named a 2018 MacArthur Fellow. I spoke with him on the phone the day after the midterm elections.

How does it feel to receive the MacArthur?

It’s wonderful to have your work recognized, but it continues to feel unexpected. Someone asked if I was going to call myself a genius now, and I was like, “Are you kidding me? Come on.”

“Experimental” writers are not often granted that kind of recognition.

I’ve been at this for a while. My experience has often been to encounter a certain level of discouragement when it comes to publishing my work, and yet to press forward. So far, it has worked out. It has not been easy, though, and I’m hardly alone in this experience.

Rereading your writing in light of the award, I’ve been trying to draw out a “Keene”-ness, to make an awful pun, throughout your work. Obviously, you’re very attentive to history and its possibilities for literature, but I’ve also been struck by your inclination towards the aphoristic, which runs from your first book through Counternarratives.

I was always fascinated by the aphoristic sensibility, by the concision of such sayings and how they do multiple things at once, their compression and surplus of naming. At the same time, rhetoric is so central to aphorism, and I came around at that hot moment of high theory when rhetoric was held in tremendous suspicion. I was working through that at the end of college and right after. It was the final years of Foucault’s life, Derrida at the height of his thing. Judith Butler and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick were writing, Stuart Hall was still alive. All these things factored into my thinking in a certain way, and carried over into my particular aphoristic sensibility, especially in the first part of Counternarratives. Because, of course, who has the authority to compress the world, to squeeze the world into these statements that may or may not be true? At the same time, I’m fascinated by the Western tradition of aphorism’s relationship to things like Zen koans or West African proverbs, which provide an elliptical kind of teaching. It can be difficult to understand what they’re actually saying, but part of the way you learn is by thinking through these riddles.

It must have been nice to come of age at a time where theory didn’t feel as exhausted as it does now. Were you at the same time cultivating this attentiveness to history that so strongly marks your work?

Well, I also studied history as an undergraduate. Back then you had to pass a general exam to graduate. You had to know about all these various areas, I remember taking history courses on Islam, Israel, Latin America. Surveying all these fields, I came to understand that the question is always how one puts the pieces together. How do you think through the contradictions, the lack of smooth connections, that we want to make between these things? I’ve always been interested in seeing how things fit and don’t fit together, which is probably why it takes me so long to write. I want to let things steep for a bit.

I was rereading Alexander Chee’s essay “Children of the Century,” where he discusses the shortcomings of a stringent verisimilitude in historical fiction, and was wondering about your relationship with factualness in what you write. There’s an ethics to your project of counter narration that I could see demanding both a skepticism towards accepted historical narrative and an assertion of how things actually might have been for people who otherwise aren’t so commonly represented.

I think about verisimilitude, and then I try not to think about it. When I’m writing, I want to think from the inside out, but when I’m done, I like to go back and try to get certain basic things right. All fiction is, at a certain level, historical writing. You write it and the day after it becomes historical. You think about what we take for granted in everyday life that we don’t usually mention in a work of fiction—what would a person in the 1800s living in a particular milieu take for granted? What would be part of the landscape that they would see because it’s just there, and what would they notice? Those are the questions I ask myself. I think if you get the emotions, key aspects of the landscape, the characterization close to right, if they give off an air of truth—this used to be the idea of the telling detail in fiction—then you’ve done more than someone who got every factual detail right but the character or scenario wildly off. Unless that’s what you want to do. If you’re playing with anachronism, as in those many works of late-twentieth-century postmodernism where writers were juxtaposing these discordant historical elements, that’s a different project.

When you’re translating, to what extent are you trying to preserve a certain strangeness of the language in its new context, and to what extent are you trying to create a more legible document for English-language readers?

It depends on the work. I fall along the lines of Lawrence Venuti, who argues at a certain level against “domestication” and for the strangeness and opacity of the source language. Of course, you want to be as true to the original text as possible, which means that it goes beyond pure linguistic facility. What is the truth of that text? And how do we carry that truth into English? It depends on the language. Sometimes work that’s deceptively simple in one language can be famously difficult to translate into another, even if those languages are quite close.

Translation and legibility are also preoccupations of your own fiction writing. Counternarratives’s very first story opens with the figure of Caribbean-born sailor Juan Rodrigues deserting his ship in 1613 to become a myriad of firsts in Manhattan: the island’s first immigrant, first black person, the first Latino, but also one of its first translators.

A friend told me he saw Counternarratives as a collection in which every story was a counter-story about the lives of artists. I agreed to the extent that many of these figures are artists of life. I’m asking how one makes something beautiful out of the most difficult conditions. But it’s also fascinating to think about how many of these stories could be viewed as translation, or the lives of translators. How do you translate these disparate experiences, these almost postmodern juxtapositions of experience taking place in the past? I’ve been thinking about how there’s a way the African American experience is almost a pre-postmodernism, a making sense of these various worlds in which you’re always engaged in self-translation from the inside out and the outside in.

It’s a self-translation that often demonstrates a painful relationship to speech. I’m thinking of Jim’s seething internal monologue in “Rivers,” which is belied by what actually comes out of his mouth when he meets Huck and Tom again. I do wonder how your friend saw “The Lions,” which is a Beckett-like dialogue between unnamed African revolutionaries-turned-autocrats in a torture chamber, as a story about artists.

It’s not directly about artists, it’s about utopia and failure. These characters were revolutionaries, idealists, they’re citing activists whose words and lives animated theirs. So often in the case of a person like, say, Mugabe, it becomes about power, replicating power and a certain colonial violence—but always using that rhetoric of revolution, because the battles of the past cannot be forgotten and were fought for a reason. But once you’ve expelled the colonizers, what world are you going to have? You’re always going to invoke the colonizers as a form of rhetorical violence against those who would stop you from raping and pillaging and stealing the country blind to fill up your Swiss bank account. “The Lions” is a counter narrative as cautionary tale, a counter narrative for all the counter narratives that came before. It asks the readers, what is the counter narrative to this? That’s the one we have to write.

Matthew Shen Goodman is a writer and editor living in New York.