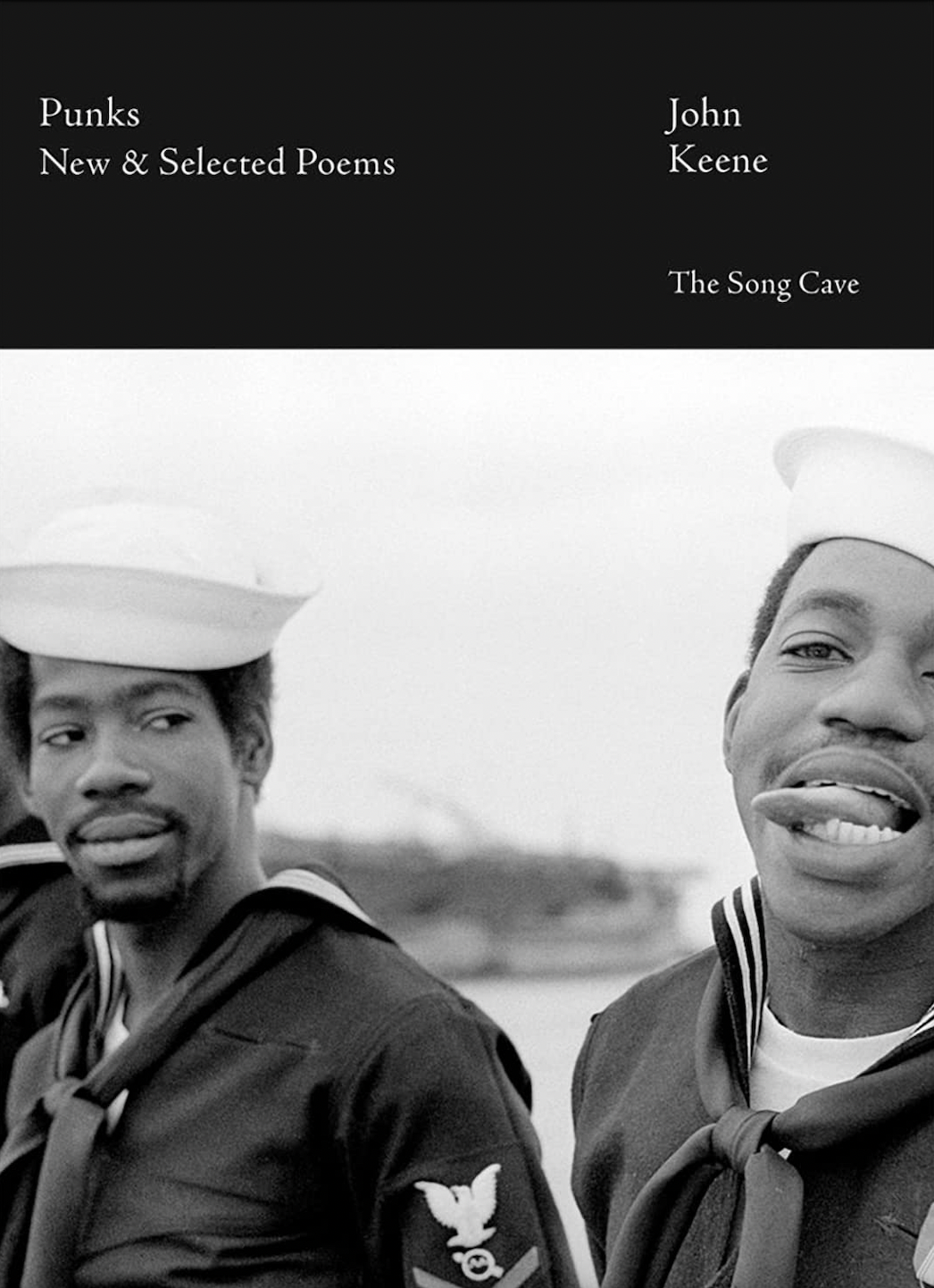

John Keene, the novelist, translator, poet, is one of these bold, singular artists who continuously redefines and recontextualizes American literature. From his debut with Annotations (1995), a prose-poem about coming-of-age in St. Louis and still ahead of our time, to the masterpiece Counternarratives (2015), Keene’s output remains undefinable for how easily he blends genres, forms, and styles to celebrate the lives and experiences of people in the Americas who remained in history’s margins for far too long. Now, with the publication of his latest poetry collection Punks, Keene brings together poetry from across three decades of his career, tethering dozens of styles into a mixtape that reflects on race, sexuality, and memory. I met with Keene in November, just before the publication of Punks to discuss the immense collection, his views on elegiac poetry, and what translated literature must teach us.

ZACHARY ISSENBERG: I wanted to start by asking what prompted this collection. Punks includes poems from various projects over the last three decades. How did the book come together?

JOHN KEENE: I feel like portions of Punks could have come out at various points over the last twenty-five years. There were moments when it seemed like earlier versions of this collection would appear, and then it just didn’t happen. At a certain point, I resigned myself to the fact that maybe it just wouldn’t be published. But it so happened that I was giving a poetry reading in Brooklyn and Alan Felsenthal, one of the editors at The Song Cave, heard me there and asked if my work was part of a collection. It wasn’t, beyond the chapbook I was reading from, but the result is this collection. In assembling the book, I went back to an older way of looking at poetry collections, which is just to bring things together. My other poetry works, Annotations and Seismosis, the collaborative project I did with Chris Stackhouse, were discrete projects. In some ways, Punks is more like Counternarratives, which is a gathering of seemingly disparate stories that cohere on many levels. When that book came out, I described it to Reggie Harris, who was in conversation with me for the Lambda Literary Review, as a mixtape, and I love that metaphor. Punks is similar in that it brings together texts that are thematically related, but also distinctive in style—or that give you a variety of styles with resonances across and within the sections. With those distinct sections and styles, I hope readers get a holistic picture of a world of containing worlds, with elements of the rhizome, of the mixtape, of life itself.

And did the sequencing come about organically?

At a certain point, I asked myself, “How could this cohere?” For several years I was frustrated, then I started to rework things. One of the things I always loved about poetry collections—especially those in this older style—is that feeling of movement, when you feel like you’re starting someplace and going someplace, even if there’s no narrative present at all. So I was hoping to create that sense of movement, and The Song Cave editors Alan and Ben [Estes] made wonderful edits, going poem by poem, making holistic edits, figuring out the right order. With the historical poems for example, I could have left them out, but we felt they were speaking to what came before and what follows them in the book. Just like the wonderful poems that I collaborated with Cynthia Gray on. And my editors took some poems out too, which is always tough! I have this one poem which is in the shape of a bunny, a textual bunny. I love it, but I could never get it published. At one point I stuck it in this collection, and my editors were like, No. They were right—there’s a place for that bunny poem somewhere, but it’s not here.

You do have “How to Draw a Bunny” in there though.

Exactly, yes. And several poems that are related to it. Which is all to say, The Song Cave’s editorial vision was really in sync with mine.

Could you tell me more about some of the older versions of the collection?

One of the earliest versions of this manuscript was called Heroic Figures, and some of those poems appear throughout Punks. I think in those earlier manuscripts, while some of the individual poems were working, the manuscript just wasn’t. But now, with this work along with a good amount of newer stuff, I finally had enough material to provide a greater sense of richness and depth, so that those individual poems that might not have worked side by side would be a part of a progression, like ripples or echoes. Rereading the older poems myself, I noticed certain key words and images over and over. I can see ghostly traces of previous versions. I began to see this inner structure of coherence that holds things together across time and across style.

Throughout this collection and throughout your work in general, you approach creation with questions. For example, you have a poem called “A Report on the ‘What’s American about American Poetry?’ Conference at the New School.” Can you speak to the questions you’re trying to answer in your work?

When I originally wrote that poem, I was outraged by some of the comments that John Hollander had made at one of the panels at that 1998 conference, and at the silence of some of the other poets there. And I thought, Well, I could write about Hollander, or about how I feel. But to me, it was more interesting to just re-pose that question. To ask again: What is the value of American poetry? Why are we writing poetry, what is it for? And of course, poetry is this incredibly powerful medium, tool, mechanism, that’s been part of every society, oral or written or both, since the beginning of humankind. It’s one of the ways that we tell stories, that we wield and demonstrate the power of language. It’s how we convey knowledge and create it, right? That’s a recurrent theme in a number of these poems, even the ones which seem like they don’t have anything to do with epistemology or knowledge-making.

And I think that interest in creating knowledge might be most apparent in the poems in the voice of Alain Locke (“Alain Locke in Stoughton Hall”) or Miles Davis (“Apostate”). Part of what I’m thinking about in that Miles Davis poem is how he’s making music, but it’s about more than making music. It’s about a life: How do you live and survive? How do you convey the stakes of what it means to be, in his case, a Black man of a certain background living in a certain time, who has this extraordinary gift? And it’s not just about realizing your gift, but also taking on the challenges that you and others like you face. How do you express that, or fail to express that? What are your limitations? These are things poetry can help us learn.

What was it like to go over the poems about Boston in the late ’80s and early ’90s?

It felt good, but strange. In some ways, these poems feel very current, and in other ways they feel very distant. In terms of LGTBQ life and lives, we’re in a different place, but all the challenges remain. That was fascinating to think about. HIV/AIDS is still with us, but it’s a very different moment than 1995 or 1985. As I was revising, one of the things that I didn’t want to do was lose the immediacy of the past.

Do you resist elegy?

Well, there are AIDS elegies in the book. I wanted to—not to write against elegy, but to think in a different way. In a poem like “Suit,” I try to push that idea, to think about what it might look like if in the process of mourning someone you say, “I mourn, but I also want to sit inside this and find something else as well.” I didn’t want to give in to nostalgia, or give people the idea that everything was so much better twenty or thirty years ago, because it wasn’t! I wanted to remember people in a way that was faithful to that time, but not solely in an elegiac way. But at one point I did worry, Am I only writing elegies? Someone once told me about a great poet who only wrote occasional poems—as if it were a bad thing. And I thought, well, you write what you write. What was wrong with that? There are people primarily writing poems in response to political events and others writing poems about deep inside themselves. These approaches can be deeply connected. You write what you’re drawn to write.

What did you learn about historicity as you edited these poems?

I wanted to stay as true as possible to the voices of these poems as when they were originally written, so I tried not to do too much editing. But I did realize that if I had had the clarity in my twenties that I have now, I would have been able to write these poems in far fewer drafts. To give one example, in “Portrait of the Father as a Young GI,” I think I had the music in my head for that poem. I had even read it, in the early 2000s at an event at Deutsches Haus at NYU, but something was just off. It took me a while to figure out what needed to be pared away in order to spring the music. And not just to spring the music, but also to capture the power of those ideas. How to get that poem to earn that final sentence. Maybe you could get there with prose in a thousand words, but it took a while to compress that feeling into a poem, and that was the case throughout the collection. My “Postcard” poems started out as one single poem, and for whatever reason, it would just not work for me. But once I decided to break them up, they could breathe, like little postcards. The idea was there. But those last things to actually make them work together? It took rethinking and rewriting to help these poems arrive.

How has translating affected your experience writing and editing poetry?

Translating poetry is a wonderful, difficult challenge to undertake. There’s always something you lose. Many poets I admire draw upon distinctive resources of the languages they write and speak and think in, and sometimes that is hard or, more truthfully, impossible to bring over to English. I thought about that as I wrote some of these poems. For example, my poem “Mirror” is, on one level, untranslatable, although a resourceful poet/translator in another language would figure out what I’m doing and come up with an analogue. What’s more important to me is not an exact translation of those sets of words so much as to capture their spirit in another language. That is something I think more carefully on when I write fiction or poetry: the richness of language, polysemy, connotation. All these things go through my head.

And what do you hope for with English translation?

I think there’s been a lot of recent interest in translations. There are so many fantastic translators of all ages and backgrounds. But there are challenges for the US publishing industry: How do you come up with a way to make this financially viable? How do you support translation, how do you get these translations out to people who’d be interested in reading them? I think of Jennifer Croft taking on Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jacob—I mean, that’s a huge book! She deserves an incredible amount of credit for a real labor of love and dedication, to bring that author’s vision from Polish to English. Or Katrina Dodson with her forthcoming translation of Mário de Andrade’s Macunaíma.

For me, it’s exciting to try to keep track of the translations coming out. And there’s an incredible profusion of work from beyond the Anglophone world, which we can hope will eventually be translated. For one, there’s Mohamed Mbougar Sarr’s The Most Secret Memory of Men, which just won the Prix Goncourt, which I hope and assume will be translated! Bruna Dantas Lobato just masterfully translated Caio Fernando Abreu’s stories, Moldy Strawberries, as well. The history of literature is the history of translation, of exchange and interchange and conversations, even as we take account of hierarchies and hegemonies. Writers, artists, and readers will read across boundaries, and that is the most powerful thing that literature offers us—to envision new possibilities.

Zachary Issenberg is a writer from South Florida, currently based in New York. He earned his MFA in Fiction from Columbia University, where he wrote two novels. He currently teaches at Lehman College, and is at work on a new book, titled Miami!. You can find his writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books, The Millions, Words Without Borders, and The Shoutflower.