Madeline Gins (1941–2014) never took anything for granted, certainly not something as foundational as language. Gins was a philosopher, writer, agitator, and architect. She is probably best known for her project Reversible Destiny, an elaborate philosophical endeavor she developed with her husband, the artist and architect Shusaku Arakawa, that questioned the inevitability of death. Over the course of several decades, beginning in the 1960s—often in collaboration with other artists, scholars, and architects—Arakawa and Gins conducted research, made art, wrote manifestoes, and designed and constructed buildings that they believed could extend inhabitants’ lives. Calling into question the fixed meanings of words was central to Reversible Destiny. Gins and Arakawa believed that continually interrogating our perception of the world, and the way we represent it through language, could transform our understanding of its basic terms—perhaps even death was not so inevitable after all.

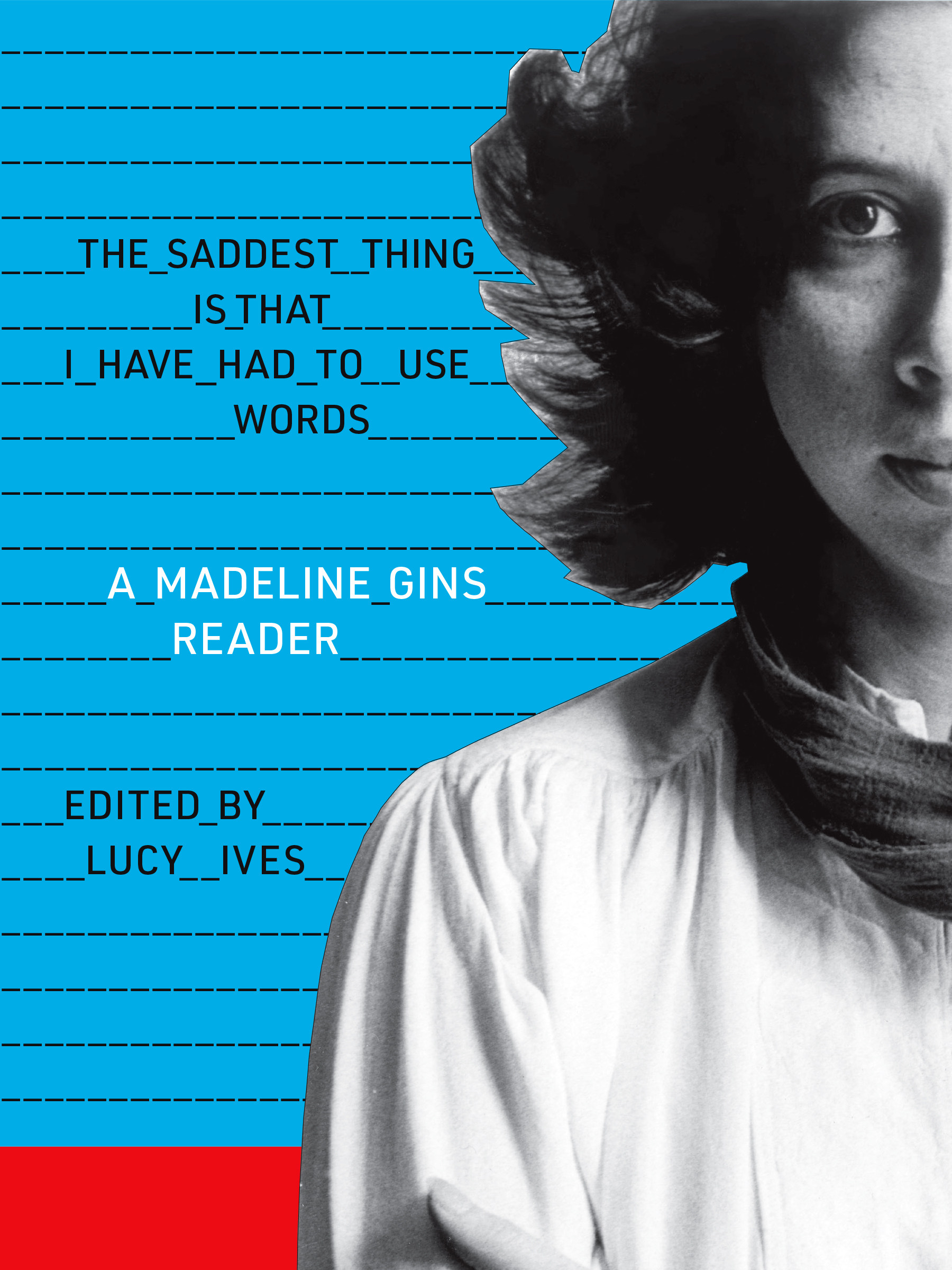

Long before she tried to remake the world through architecture, Gins wrote poems and novels that experimented relentlessly with words. The writer and scholar Lucy Ives has edited a new anthology of Gins’s previously unpublished and out-of-print work, The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had to Use Words. The volume centers Gins’s early experimentation with language, showing how her poetry was engaged in much the same world-expanding project as her architecture. “Poetry may be writing, of course, but . . . it is also image, performance, gesture, song, social life, gossip, furniture, food, shelter, dance, research, email, garments,” Ives writes in her introduction. “Madeline Gins is the one who taught me that.”

We’re talking in the midst of a pandemic, and the world feels upside down. Which is a fitting time to be thinking about Madeline Gins. I’ve been wishing that I could talk to her about all this, and wondering what she’d be doing, or writing, under quarantine.

I’ve been thinking a lot about her long poem “What the President Will Say and Do!!” It’s supposed to be a parody of executive speech. But it also functions as a series of impossible tasks that are available to anybody who might be interested in them. I think if she were here, Gins would come up with a series of playful tasks. And she would continue to discover new kinds of space within the space of quarantine. My intuition is that she would be very good at it.

Let’s go back for a minute. Gins flies under the radar for most people. How did you find your way to her work?

It happened when I was in poetry school. A very strange place to be, and I was an extremely awkward person. In Iowa City, there’s a bookstore called Prairie Lights where people gave readings. Whenever I went to one, I would pretend to be very busy browsing the books beforehand, so that no one would try to talk to me. Once, I was looking through the art books and I saw a big hardcover catalog that said “Arakawa/Gins” on the spine. I took it out and started looking through it and I was like: “What is this? Is this an architecture manual? Is this a projection of a utopia that people were going to build—and did they build it?”

I went to the library the next day. The University of Iowa library had a very thorough collection of poetry and experimental fiction in the stacks, including Gins’s WORD RAIN. I looked at it and was shocked by how weird it was. I was like, “This is not allowed—how is she doing this?” She’s making the pages into images, she’s included photographs, and the writing is so precise but also funny and strange.

I don’t think I threw it on the ground and ran away, but it was definitely one of those books where you put it back and you’re like, “I need to think about this for a little while.” This was the time of WMDs, when all of this invented language had become part of the larger culture. Seeing the ways that Gins manipulated language was a release, an escape from that culture. What she was doing was transgressive, but she had manipulated language in a way that was so much more extreme and intelligent.

When you tell this story in the book’s introduction, you mention that Madeline Gins was firmly not being taught in your MFA program. In that context, encountering something as off-the-wall as her work probably seemed even more bizarre.

It seemed like, “Oh maybe this person doesn’t understand that you’re supposed to write poems that will be published in literary magazines.” There was a sad version of me that was capable of that thought.

Who were Gins’s fellow-experimenters? And did your sense of her writerly family tree shift as you spent time in her archives?

The most obvious person in that family tree is probably Gertrude Stein, who was interested in space and language in a very particular way, one often read as an extreme high-modernist stance. But scholarship has shown that it was a kind of secret language that she shared with Alice B. Toklas. So, her writing is part of a domestic practice. That’s also something important to think about with Gins. She was trying to figure out a way to have a productive, collective life that is not based on the nuclear family. As she was reimagining the association of people one grows and learns and works with—her writing was part of that as well.

But I think you can put Gins in the context of various experimental traditions. I put her with Hannah Weiner, who was a friend of hers. Weiner was also an underwear designer, and had a practice that wasn’t just writing poetry, but also involved performance and the fabrication of semiotic objects of various kinds. And I think about the poet Bernadette Mayer, and her sister Rosemary, who’s a visual artist and worked a lot with fabric. And there’s the artist, writer, and philosopher Adrian Piper.

She also fits in with writers who had experimental or very capacious conceptions of what the book object could be. I like thinking about Laurence Sterne—you know the black page in Tristram Shandy—in relation to WORD RAIN. The idea that the act of writing and the existence of the book can, in this kind of impossible twist, be folded into the narrative, so that the existence of the book is foreseen within the fiction, as well as the existence of the reader. That kind of reflexivity—what people now call metafiction. Once we start thinking about Gins that way, we can fit her into the American tradition at a different level of experiment, along with what I think of as a group of men who’ve been taken very seriously.

As a poet, there is a singularity about her. There are ways in which literature is always threatening to jump out of its disciplinary boundary. That’s one of the most interesting things about it—it’s always trying to invade other disciplines and take them over. You can see that in spaces like literary theory, for example. You can think about Gins lots of different ways, but she seems most unique if you think about her as a poet.

On that note, let’s talk about words. In all the writing collected in the book, it feels like Gins is in a constant, very physical, relationship to words, whether it’s wrangling or playing—or many other things. The book could be read as one story about Gins and a character called “Words.” How did you come to understand her many stances toward language?

It’s interesting, when you look in the archives, there’s a lot of unpublished material from what I believe is the 1960s and ’70s, a period of just incredible productivity for Gins. In the beginning, she had a typewriter practice. You see a lot of typewriter use in text-based conceptual art, and I don’t think it’s just because that was an available technology. A typewriter is very physical, in a different way than a laptop or even a pencil is, because of the specific sound, and the time between when you strike the key and when the letter is struck onto the paper. It’s like a hiccup. There’s an anticipation, and then an event takes place. Working with the typewriter allows us to kind of stumble around words, and to see the materiality of their spellings, their art of orthography, and the number of character spaces that they take up, in a kind of fuzzy, inexact way that can lead to innovation. Gins produced at least one pretty long, strange, stream-of-consciousness novel, which she never published, about a woman whose body seems to dissolve. That was really something that couldn’t be excerpted.

I think some of Madeleine’s work in this period is related to the Natural Language Philosophy trends of the time. People are exploring the surprise that language exists at all, and that it may structure our very thoughts. There’s what I would call an aesthetic, categorical relationship to language, and there’s also a very rich materialist relationship to language that comes out of her experience with the typewriter. You get a sense of her sensorium merging with this typewriterly sensorium. That’s something that continues. Gins and Arakawa had personal computers in the 1970s. I really don’t know of that many other people who did. They collected computers, basically. There is a movement you can see in in the archives, from this prodigious activity with a typewriter, into, as time goes on, being able to do research not just in print but online. And once you can go online, then it’s like, “Woo!”

I love the idea of the typewriter as an object that allowed her to manipulate and work out questions about words. It makes me think of something she said the very first time we talked: “Language is so magnificent, but it falls into these terrible word traps.” Thinking about the disorienting way politicians use language now, Gins’s comments feel very prescient, don’t they?

Certainly, toward the end of their careers, not just Gins, but also Arakawa, were very adamant that the problem wasn’t just in space and design, it was in language itself. In terms of Gins’s early work, in the many list poems she wrote—some of which I have included—there’s a refusal to engage in the composition of full sentences. Syntax is being removed. Language is losing certain kinds of agency that it previously had in sentences that normalized what it does. We’re being forced to experience it as recalcitrant items that designate. I think she’s looking at a certain kind of violence in language, but also an instability, a sort of bluster, lots of different surfaces and textures.

Neither Gins or Arakawa were, in my opinion, particularly dogmatic in their relationship to language. There was always something about going back to explore experience, and to try to destabilize any hierarchy where language comes first. A lot of the time they’re trying to get in front of language. I think they believed that there was another register of language that was being forgotten.

In thinking about Gins and Arakawa’s work in Reversible Destiny, I always came back to the idea that it’s a project of deep optimism. Remaking language was obviously part of that. How do you see the actual work of trying to remold language happening in Gins’s writing?

She’s working so hard during the ’60s and ’70s to excavate and test words as much as she can. She’s combining sets of fairly common words: “MATH DESK,” or “FLOWER AND BURNT SECRETS.” There are so many sets of things, like “waterfall skin,” “shadow bitten”—phrases where the words are not unfamiliar but the combination is. And sometimes she’ll mix these juxtapositions with juxtapositions that we do know, so that we notice both the strangeness of the strange juxtaposition and the strangeness of the familiar one.

It’s those kinds of things that she’s trying to get at and ask: What is noticing and what is not noticing? And if I can notice noticing, and then I can train myself to notice what I previously was inured to noticing, then what can I notice after that? Language is the medium in which she establishes this style of noticing. Emily Dickinson is the American example bar none of someone who is training herself to see things that aren’t traditionally, customarily visible, using language as a means of seeing. Which gives some sense of the importance of what Gins was doing.

That’s what Gins’s work as a young writer is about. And I have to assume that she used what she learned from these experiments and these poems to develop the Reversible Destiny project with Arakawa.

But I’ve tried to resist seeing the writing as the adolescent phase of Reversible Destiny. I sometimes feel like Gins didn’t do herself as many favors as she could have as a writer. I think she was pretty clear on the fact that she was, you know, pretty smart! I don’t think she was confused about that. But maybe, on a certain level, she didn’t quite realize how great her writing was.

Amelia Schonbek is a journalist who has written for New York magazine, the New York Times, The Awl, Hazlitt, and other publications.