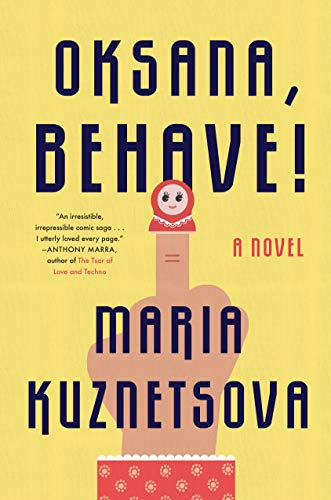

Maria Kuznetsova was born in Kiev, Ukraine and moved to the United States with her family as a child. She lent some of her biography to the heroine of her debut novel, Oksana, Behave! The novel’s eleven chapters are episodic, beginning with Oksana and her family’s immigration to the US in 1992 and continuing on through a series of mishaps, losses, and adventures as Oksana haphazardly enters adulthood.

Our protagonist is clever and impulsive—a fiery misfit. As a child in Florida, she dials 9-1-1 to find out whether the service really “works” and tells the dispatcher “My grandmother is trying to kill me!” As a young adult, she pursues an ill-advised fling at a New York apartment party and ends up robbing her host of his prized key to Gramercy Park. On a trip to Yalta, she conspires with her grandmother’s suitor, helping him win her heart—at least for one night.

The novel’s propulsive force is Oksana’s relationship with her family—her worried, depressive mother who often calls her “little idiot!”; her reserved but tender father; the little brother she dotes on; and her grandmother, a tireless force forever seeking her next affair, regularly dispensing hard-earned wisdom and witty takedowns. In leaving Kiev, Oksana’s parents and grandmother have left behind beloved family members—living and dead—and beneath the novel’s comedy lies the murk of painful histories, both personal and collective, which are part of Oksana’s inheritance.

I recently caught up with Kuznetsova over Skype and discussed Kiev, her relationship with the fictional Oksana, and the need for more stories about roguish women.

The plot of this novel is episodic, almost like a short-story collection. How did you go about choosing the parts of Oksana’s life to illuminate?

The book that was most on my mind when I was writing Oksana, Behave! was Tom Perrotta’s Bad Haircut, which consists of ten vignettes that span about fifteen years of a boy’s life as he grows up in New Jersey. My own coming-of-age took place in several states—I went to about five elementary schools—and I wanted to write a coming-of-age story that consisted of little love songs to the places I’ve lived. Once I knew that, one chapter kept leading to another. For example, an earlier draft of the chapter “Onward to the Bright Future” included a poem Oksana wrote about her dad delivering pizza. When I later cut that part out, I moved the detail about Oksana’s dad, who held a day job as a physics professor and delivered pizzas in the evening, to another chapter. It wasn’t that big of a plot point, but the father’s need for a second gig was emblematic of her family’s struggle to make ends meet in a new country.

Were there any other novels that influenced this project?

Sergei Dovlatov is a Soviet dissident who writes about the absurdity of immigration, and his deadpan, hilarious style was a big influence on the book. In general, the idea of the Russian rogue character—I’m thinking of books like A Hero of Our Time, Oblomov, or Eugene Onegin—was in the back of my mind. I wanted to write a female character who also had roguish or rebellious tendencies. I thought, why not have a drunken woman getting into trouble?

It’s interesting that you were thinking of this as fitting into a Russian lineage of stories about men. There are so few examples of literary women behaving badly in the same way that literary men often do. Were you thinking of the novel as an explicitly feminist undertaking?

I wouldn’t say I was working toward an explicitly feminist project, but I think one of the reasons it took me so many drafts to write some of the chapters, was that they forced me to reflect on myself at the most repulsive time in my life. The chapter “Onward to the Bright Future” was an example of this. It focuses on Oksana’s last year at Duke, where she is partying, drinking too much, consumed by her hookups and crushes, and being confronted with an assault allegation against her friend—all while the Duke lacrosse rape case is taking over the political conversation on campus. I probably wrote three hundred pages to get that one chapter, and I feel like it’s still unwieldy. I was at Duke during the lacrosse rape case, and I’d been trying to make sense of it in the years after. I don’t think I was more repulsive than other people in college, but I wasn’t engaging with things the way I would now. In writing about it, I had to acknowledge that I (and by extension, Oksana) didn’t care very much about the important political issues going on around me and was more focused on my romantic drama. In the first drafts, Oksana was offering all this commentary on race and sexuality, but that wasn’t true to the way she would have experienced her life at that age.

In thinking of way to describe Oksana, a word that kept coming to me was “loyal.” She’s not always loyal in traditional ways—she sometimes lets down the people she loves—but she seems loyal to greater ideas about freedom, and she’s true to her own principles, which sometimes leads to her “misbehaviors.” How were you thinking of Oksana’s refusal to “behave”?

Oksana is definitely selfish a lot of the time, but I like to think that she usually means well— especially as she gets older. I wanted her to be someone I could root for, even if she does questionable things. For example, in “Key to the City,” I wanted to show how loyal and loving she could be to her brother, all while being pretty cruel to the men in this douchey apartment party, including a well-meaning guy who might genuinely love her. Some of my early readers thought “Key to the City” should be two separate stories—that those parts of Oksana didn’t fit together—but I wanted to flirt with the extent to which she could contain all these impulses at once.

There’s a Russian way of looking at the world, in which people are either yours, or they’re strangers. I think Oksana has a bit of that worldview. Her brother is hers, but the dudes at a party, or even a random guy she hooks up with—they’re just strangers. That kind of mindset can lead to deep loyalty to your family but a lack of caring for other people. I think she carries that with her a lot of the time. It can get you into trouble.

That’s so beautiful, and it makes me think about how deeply Oksana’s grandmother belongs to her. How did your relationship with your own grandmother influence the book?

My grandmother definitely was a force—a larger-than-life person and the most positive and fun- loving woman I ever met, in spite of the fact that she survived World War II as a child and lost her young husband and daughter within the span of five years. She followed my family to the States and returned to Kiev to retire when I was a freshman in college. She died while I was writing “The Yalta Conference,” the chapter about Oksana’s trip to Yalta with her grandmother. Because she passed away right when I was starting to see Oksana’s stories as chapters in one book, she became the through line for the novel.

When I visited her in Kiev, she would take me on long walks around the city, to ballets and shows at night, and once to Yalta, always talking about how she had been all over the world, but Kiev was the most beautiful place of all. My grandmother and Kiev are forever intertwined for me.

It’s interesting that Kiev is such an important place in the book, even though so little of the story takes place there. Is your relationship to the city similar?

For a long time, I wasn’t curious about my Russian heritage. I left Kiev as a child and grew up in a Russian Jewish community in New Jersey, so I felt so inundated with it. I was either embarrassed or indifferent at best. When my grandmother moved back and I returned to Kiev for the first time since I was six, I was also beginning to write seriously. Kiev became this place I wrote about—full of nostalgia, and confusing, because I remembered it, but I didn’t. Kiev is at the core of who I am, but I also feel very foreign whenever I go there. My accent is terrible, people make fun of me, and my vocabulary is super limited. But Kiev is this thing we talk about at the dinner table. My parents and their friends are always reminiscing about it. The experience of Kiev is something I feel left out of but that I’m very curious about, and I think the same is true for Oksana.

Do you think your relationship with Kiev will be a lifelong theme in your work?

I still think about Kiev a lot, though I haven’t been back since my grandma passed away. It’s already been three years, and I don’t see myself making the trip anytime soon. It makes me kind of sad. My next book is about a teenager whose family flees Kiev during World War II, so there’s still a kind of nostalgia and focus on the city, even though it’s very different from the Kiev I know and love.

I might also write other Oksana stories, to bring in more of what happens in my own life. I want to keep having fun with it. I think any story that interests me about my life will be an Oksana story, unless there’s some reason why it can’t fit into the character’s biography.

It sounds like you think of Oksana as your literary alter-ego.

Oksana and I are not exactly the same. I met my husband when I was twenty-two. I have not had an exciting dating life, and I’d like to think I treated my family and the people around me with a bit more grace. A lot of this was taking my impulses and making them much more dramatic. A major difference between Oksana and me is that she lost her father, while mine is still alive. I think that made me stretch my imagination, because her loss influences everything that happens after—her relationships with men, her motherhood, her job.

I want to write many other things, but my vision is that Oksana can continue to be something I’m always working on. I already have a few new Oksana stories in the pipeline inspired by the birth of my daughter. If I do write another Oksana book, I think the next one will be done in, like, ten years, because I need to live a little more first.

Alex Madison is a writer based in Seattle.