Novelist Bernardine Evaristo is the consummate traveler, having led a peripatetic life since her teens. This adventurousness extends to her creative work, much of which starts off in one genre, only to end up in another. The Emperor’s Babe, which tells of the life and times of Zuleika, a young Sudanese woman who is “a nobody wanting to be somebody,” was conceived as a series of poems, but was eventually published as a verse novel incorporating unrhymed couplets. Blonde Roots has roots in a short story commissioned by The Guardian. Girl, Woman, Other, a protean, polyphonic novel that won the 2019 Booker Prize, started as a narrative poem for radio.

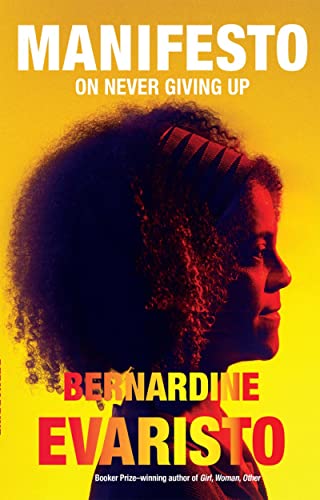

The process of writing Manifesto: On Never Giving Up was relatively straightforward: Evaristo always knew that it would take the form of a memoir. But the new book continues the author’s interest in transformation. Manifesto recounts Evaristo’s experience growing up in a working-class neighborhood in South London with seven siblings. Born to a white mother and a Black Nigerian father, Evaristo experienced early on what it was to “be regarded as a sub-person: submissive, inferior, marginal, negligible—a bona fide subaltern.” The book is a testament to her “unstoppability”; she looks back on how she refused to conform to society’s low expectations for her and made a creative life for herself—first as a poet and playwright and later as a novelist. Currently a professor of creative writing at Brunel University London, she has written numerous plays and novels that explore white British colonialism and the African diaspora. In 2021, she was announced President of the Royal Society of Literature, becoming the second woman—and the first writer of color—to lead the organization in the two hundred years since it was founded. Evaristo and I spoke over Zoom in March about her new memoir, fusion fiction, and constructing the sound chambers of her novels.

Your descriptions of drama school are some of the most interesting in Manifesto. You call them “intense laboratories that demand a high degree of self- and group interrogation. . . . The unthinking self is dismantled so that you can be rebuilt with a deeper understanding of who you are, which in turn enables you to create convincing characters.” Can you say more about your immersion in these hothouse environments and how it informed your later writing?

When I got to drama school, I realized that acting was about consciously working on yourself in order to know yourself in order to be able to play other people. Before I started drama school, I wasn’t able to cry. I guess I’d toughened myself up to the realities of my life. I learned to cry at drama school. I had to peel back the layers of myself to understand myself. The whole three years was this intense laboratory. When you compare that to a traditional university, it’s very different. With most subjects, you’re not really encouraged to explore who you are. You’re encouraged to learn things, which can be a very external thing, but not to explore your essence and get in touch with your vulnerability. That’s what I gained from drama school. I also learned about collaboration and listening to my fellow theater makers. The process of self-interrogation and connecting to my emotions shaped me as a writer who feels the need to connect emotionally to her characters. If I can’t connect emotionally to my characters, then the writing appears very dry, and I lose my passion for it.

When you started writing poetry, you had no formal training. Now, there are a variety of classes one can take to get up to speed on the art of crafting of poem. Do you think your poems would have been different if you had taken poetry courses at universities?

Absolutely. I’m a very single-minded person in terms of my creative practice. I could not entertain the idea of being taught how to write when I was a younger person. Also, there weren’t a lot of creative-writing programs in Britain in the early 1980s. There weren’t that many workshops around either, and anything that was around was taught by white people. I felt that if I was going to be studying creative writing, it would need to be in the Black women’s space. In my younger years, that didn’t exist. My books are all experimental in different ways because I had to find out how to do it myself. I didn’t have anyone teaching me even the basics—line endings, imagery. The pedagogical poetry books were prescriptive and limiting. I just learned through reading poetry and then trying it out myself.

I know that Derek Wolcott is one of your favorite writers. What about his poems draws you in?

When I read Walcott, I fell head over heels in love. His writing is just so beautiful. But it’s also politically, culturally, and historically complex. There is a sense of foreignness about his work; obviously, a lot of his work is rooted in the Caribbean. Even though I’m not Caribbean, I was entranced by the way in which he wrote about the Caribbean, which spoke to me much more than anybody writing about life in Britain. White feminist poetry did not speak to me as a woman, but there’s something about Wolcott’s subject matter and the complexity of thought and beauty of his language that I found incredibly inspiring. I also love the fact that he could turn the ordinary into the extraordinary through his use of imagery. His writing is exquisite in that way.

You mention in Manifesto that you’ve often thought of your father as a Yoruba warrior. I wonder if I could ask you to say more about the influence of other traditions in your novels, whether African or ancient ones that may not be legible or visible to readers from the US or UK.

I didn’t encounter a lot of African writing as a young woman. It really was a cultural desert for me as a Black British woman looking for stories that in some way spoke directly to me. Most of what existed when I was young was written by men about men. In my twenties, I was drawn to African American women writers who were centering Black women in their stories, writers like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Michelle Cliff, Maya Angelou, and Ntozake Shange.

You write that you weren’t always a fan of Virginia Woolf. I was surprised to learn this because I think there are similarities between some of Woolf’s novels and Girl, Woman, Other. Superficially, you both dispense with some novelistic niceties and disrupt conventional paragraphing and punctuation. I think a work like The Waves shares a lot with the style you have termed “fusion fiction”: a hybrid style that pushes prose towards free verse, allowing direct and indirect speech to seep into each other and sentences to run on without full stops. Did your rejection of Woolf have to do with a larger sense of modernism’s elision of race?

So many writers cite Woolf as a major influence on their own practice, and they have done for many decades now. When I say that she wasn’t an influence on my work, people are slightly shocked and appalled. How could I not revere Virginia Woolf? But actually, as a young woman I was writing against Woolf. The first book I encountered of hers was To the Lighthouse, which was taught at school. I found it very painful to read. I didn’t understand it. I wasn’t interested in it. It wasn’t particularly well taught by the teacher. Even though I don’t cite Woolf as an influence, I do think others have been influenced by her. I am a writer living in this world, reading lots of books, by writers who have probably been influenced by Woolf. So it’d be disingenuous for me to say that I haven’t been touched by her work. Because I’m engaging with lots of literature and other people have been touched by her. I find myself in direct conversation with Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf. Not that we’re doing the same thing because we’re not. But Shange’s play had such a profound effect on me as a young Black woman. Going to theater in London in 1979 and seeing that live on stage—it was like, my God, all these Black women on stage! And there’s seven of them! And they’re American, which was incredibly glamorous and beautiful.

You write compellingly on the upshots of leading a nomadic lifestyle: “When you move around a lot, you have to be mentally agile and adapt quickly to new environments. Moving home as much as I did forced me to live by my wits, which I reasoned was no bad thing for my creativity.” Yet leading a “creative life” also “led to peripeteia and precarity.” In your twenties and thirties, you chose to rent instead of taking on a mortgage—“essentially a twenty-five year debt,” you called it. After years of resistance, you’re now a homeowner. If the stability that homeownership confers is the opposite of precarity, what’s the opposite of peripeteia for you?

It’s also stability. It’s very interesting, because when I was writing the memoir, I wanted to present my life through a positive prism. I was thinking about how I’ve reached this point and realized a lot of people wouldn’t be able to deal with the nomadic lifestyle that I’ve had. It would throw them off course and they would stop writing. Initially, I enjoyed moving from home to home, it was exciting. And then I reached a point where I did want stability, but it wasn’t forthcoming. There was this tension between a lifestyle that wasn’t stable and a career that was in a way, because I always kept writing. I was never complacent; my life was never comfortable financially or home-wise. Sometimes complacency can be the death of creativity. What I don’t talk about in Manifesto is that I also have traveled a hell of a lot. I was on the road for a couple of years at one point. Now when I’m on the road, I’m just traveling for work. It’s not as interesting.

Your father’s heritage is Nigerian and African Brazilian, and I’m wondering if you plan to travel to either of those countries for a book tour?

I haven’t been on a plane for two years. I’ve quite like being grounded. I was supposed to tour in the US for a month in January, but that was cancelled because of the Omicron wave. Next year, I’ll be back on the road and I’m really looking forward to that because I’m supposed to be in Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Trinidad. I was in Nigeria in 2019, after I won the Booker. I would love to go back with Manifesto. I was supposed to be physically in Brazil, and will probably there next year.

You were recently elected as President of the Royal Society of Literature. How does it feel to be the first person of color to helm this institution?

It feels great. I call myself Madam President. When I think about where I started in the arts and where I am today, I’m still having many pinch myself moments, because it’s been a forty-year journey. I left drama school in 1982, and I broke through at the age of sixty. I’m president of this very august organization, which is also progressive. It is a diverse and inclusive organization, especially in the last few years. For me to be the figurehead of such an organization feels like a personal achievement, but also a symbolic achievement. I don’t share a background with other people who have occupied this post.

You’re also involved with Penguin UK’s “Black Britain: Writing Black” series. How do you choose which books to include?

I’m looking for Black British books that have been published in the past and that deserve to be republished and to reach a new audience. I’m very aware of Black British literary history. I’m more aware, I think, than anybody in publishing because publishers often only know about the books that have done well, books that have been part of the canon, which have primarily been by white men and some white women. Very few Black British writers have been allowed into the academic canon or canons. Somebody who’s in publishing has probably come through a traditional English literature education, where they wouldn’t have encountered Black British writing. For my Ph.D., I wrote about Black British writing and have been involved in it for a very long time. Also, I’ve known many of the writers and so I kind of relied on my own resources in order to find the books and sometimes asked other people who are also knowledgeable about it for their recommendations. I read every book that was a contender and then I made my decision about whether this was a book that felt fresh and also somehow relevant to our times.

In Manifesto, I found the section about your “torture affair” with the “Mental Dominatrix” painful to read. You tell us that she exercised control over almost everything in your life: “she was top dog in the hierarchy of our coupling, and it was her duty to tell me where I was going wrong with my life, my thoughts, my friendships, my associates, my everything.” Was that the most difficult section of the book for you to write?

I don’t think it was, because I’ve been dining out on that relationship for a very long time. It’s just, like, juicy gossip and I got over it a very long time ago. Thirty-seven years is a very long time ago. So I had fun talking about that relationship and writing about it. I think the difficulty was talking about not finding a relationship when I was having relationships with men. There’s something slightly humiliating I think about not being able to find myself in a proper relationship and also owning up to that was difficult. It’s not something I’ve ever written about, and I did have to think quite deeply about whether I wanted to go there with it. That was the main stumbling block for me: Am I going to really tell people about having all these unsuccessful relationships, or am I going to gloss over it? I decided to go for it. And once I decided to go for it, I got rid of my fear of talking about it, simply by talking about it.

Your book Lara was updated in subsequent reprintings. You note that for a 2009 reprinting, you “changed the poetic form, breaking down the page-length blocks of poetry into more readable two-line stanzas.” You also wove in more fictionalized family narratives from your German and Irish ancestors, and you tantalizingly write that “one day I will add new family narratives to it.” I find this idea of going back to a finished work and updating it so interesting. Do you often feel the itch to go back and revise your other novels? How do you know when a project has been finished?

I don’t have the impulse to rewrite any of my other books. It’s just that book, and that was because it went out of print. So I needed to find another publisher. And at the same time, I was made aware that I hadn’t gone into my Irish history and my German history. And suddenly I’m very excited by those two strands of my family history. The book is semi-autobiographical; there are whole sections about me and my parents and my early life and it ends about thirty years ago. There’s been so much movement in my life since then. I didn’t know when I wrote Lara that I could track my history back three hundred years. I feel that this book will probably never be complete. And I look forward to the next stage when I add more material to it. With all the other books, I feel they’re finished, there’s nothing more to do with them. I have developed a very strong sense of when a book is done. I don’t think I had that quite so much when I was a younger writer, and that is often the problem—you don’t know where to finish. But now I have this really strong sense that everything is coming together towards the end of a novel. There’s an automatic process that happens with me, and maybe it happens with other writers: there’s a circularity to fiction. Towards the end of a book, you start to refer back to the beginning. There are echoes of what’s happened at the beginning in some way, shape, or form. And when that starts happening naturally without me shoehorning it into the narrative, I’ve come to the end.

In Girl, Woman, Other, the very name of the queer theatre director, Amma, is palindromic, and it rhymes with the formal symmetry of the novel, which opens and closes at a theater.

I absolutely love that. I’ve never thought of that. We just write the books and then people come and they see the patterns and the rest of it.

Rhoda Feng is a freelance writer whose writing has appeared in the New Republic, Jacobin, the White Review, 4Columns, BOMB, and elsewhere.