In 1999, Richard A. Clarke, the US Counterterrorism Czar for Clinton and Bush, wanted to attach Hellfire missiles to unarmed Predator drones so that he could kill Osama bin Laden. In the months before September 11, Predators set their cameras upon the al Qaeda leader several times, but Tomahawk cruise missiles—then the only option for unmanned strikes—took hours to reach Afghanistan from the launch submarines off the coast of Pakistan. After the attacks, lethal drones were an easy sell.

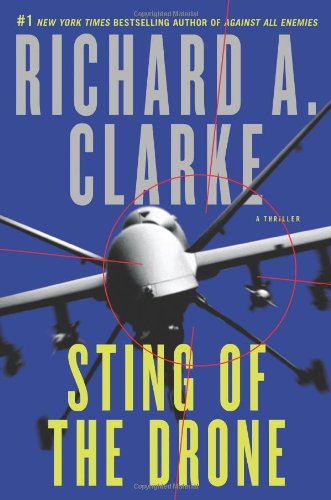

Thirteen years and four-hundred covert drone strikes later, Clarke has written a thriller about the program for which he admits “some personal responsibility.” Sting of the Drone, Clarke’s third novel and seventh book overall, imagines a presumably not-too-distant future in which the US, entrenched in a “never-ending circle of retaliations” against a global narco-terrorist network with “more money than God,” has extended its drone war to Turkey, the Philippines, and even Austria. The scale of the war keeps expanding, as does the moral uncertainty. Invariably it all starts to backfire. Indictments get served, human rights investigations are opened, the “bad guys” get drones of their own, and a lot of people get blown up. Clarke is not just spinning a yarn; he’s issuing a warning.

In conversation, Clarke is succinct, precise, and just a little terse. He spent three decades in Washington, working on every national security crisis from the Regan administration to the Bush administration. At one point, bin Laden put out a contract on “the American Terrorism Czar Dick Clarke.” Clarke’s response—“Well, that’s not surprising, since I’m trying to get him killed”—sounds like a snippet of dialogue lifted from a high-tension thriller. As an author, Clarke is just as comfortable creating a world of fiction as he is discussing his own reality; in his case, the two aren’t so different.

How have you found the experience of writing fiction different from that of writing nonfiction?

Well, I thought that writing fiction would require less research, but the truth is that even fiction requires a lot of research. And so the differences are, I think, largely in the style. In the nonfiction book you have to be far more expository and logical. And in the fiction you can be more subtle.

You are eminently readable, both in fiction and non-fiction. What are you seeking to achieve in the style of your prose?

I think in both fiction and non-fiction I’m seeking to lower the barriers to entry, so that a reader, once he or she picks it up, will keep going and not put it down after the first chapter because it’s too polemical, too one-sided, or too technical. I’d like to have a broad range of people be able to enjoy the book.

What writers have been particularly influential in the development of this style?

I hope I haven’t copied anyone, but I certainly appreciate John le Carré. I appreciate Alan Furst. In the spy genre, David Ignatius is doing a wonderful job. And then there’s Dennis Lehane, who in his crime stories has a marvelous ability in dialogue—I think that’s extremely hard to do. I tried to master the art of dialogue, but it’s difficult.

Is it a challenge to crystallize these extremely complex issues in engaging narratives?

Less than you might think. It’s certainly a challenge. But in my government career I spent a great deal of time having to explain fairly complex issues, in writing as well as orally, to senior-level people who didn’t have a lot of time and didn’t have a lot of technical background. To write for a President or a Secretary of State a one-page, typewritten memo on a very complex issue was perhaps the highest challenge of any writing task.

Though Sting of the Drone is a novel, there’s also a sense that it’s an attempt to sway public opinion and even national policy. Would you say that’s a fair analysis?

Not a lot of people who have read it have asked me which side I am on, so if it’s an attempt to sway policy in a particular direction, it’s apparently well camouflaged.

I’ll rephrase the question: Are you frustrated with how things have gone with the use of unmanned aerial vehicles for targeted killing, and is the book an attempt to explore some of those frustrations?

The book is certainly an attempt to explore—I was going to say the both sides, but it’s really the many faceted sides—of the issue. Or issues. I hope, subtly. I hope no one reads this book and says, “Oh, he’s definitely for drones,” or “He’s definitely against drones.” I hope that all the arguments have been aired, not in long soliloquies by the characters but by events in the plot.

President Clinton used to read Tom Clancy thrillers late at night and what he read in those books—even though they were fiction—would influence his opinions and ultimately some of his policies. Is it your hope that members of the Obama administration, or indeed Obama himself, will read Sting of the Drone?

I can attest that the stories about Clinton are true because I was the one who usually ended up with the novel on my desk the next day, with Clinton saying “What if this is true?” or “What are we doing about this—could this really happen?” I don’t know what Barack Obama reads. I’m not sure I’ve seen a story about whether or not he reads this sort of book. I would hope he’d read it. But I suspect that, having done his policy review last year on drone policy, he knows the arguments just as well as I do. I read through his speech on drone policy at the National Defense University on May 23, 2013. It was quite clear to me that he had written large parts of the speech himself and it was a very thoughtful speech that was informed by a long process of reviewing the issues about drones.

What do you think has changed in the year since he gave the speech?

When Obama announced a year ago a new set of rules on the use of drones, we anticipated that there would be far fewer drone attacks, and in fact there have been far fewer. It’s much more difficult now to do what’s called a signature strike, in which you’re going after facility because the facility fits the signature of a terrorist camp. You must now be able to demonstrate that there’s imminent danger of an attack against the United States, not against some other country. Those are high bars to mount, and the result is that there are far fewer attacks happening now.

In Your Government Has Failed You: Breaking the Cycle of National Security Disasters (2008), you describe how when you started out as a young man working at the Pentagon, you had the “lofty” goal of preventing unnecessary wars in the future. Do you think that the drone campaign qualifies as such a war?

That the drone campaign qualifies as an unnecessary war?

Yes . . .

No, no. First of all, it’s not a war. It’s the use of a particular type of weapon embedded in a different kind of war. If you think that we’re at war with al Qaeda, which I think would be fair characterization, the drone program is just a weapon. It’s a weapon that was chosen in the belief that it would cause less collateral damage. It would be more precise than any of the alternatives that were available. In the event, it has, nonetheless, created a lot of collateral damage.

Sting sets the US and its adversaries in a “never-ending circle of retaliations.” Is this already happening in reality?

I’m pretty sure that it’s already happening. I think that when villagers in Iraq, for example, had their lives turned upside down when their mothers or fathers or cousins or tribe members were killed by the invading U.S. Army, that probably created more anti-American terrorists than anything else anybody had ever done.

One of the criticisms of the drone is that the pilots aren’t in danger. And yet I’ll say, without giving too much away, that in the book the pilots are in danger, in very immediate danger.

That’s right. The argument that it’s an unfair fight because the pilots aren’t in danger has always seemed very unpersuasive to me. I think American commanders have always felt an obligation to try to reduce the danger that their troops are in. For a long time we thought that the drone was the ultimate achievement in that regard. It totally removed the pilot from any danger whatsoever. I suspect that may change over time, and I certainly play with that idea in the book. But there’s no need, in my mind, for a fair fight. The question is whether you want to have a fight. Do you want to go after someone for whatever reason, to defend yourself or otherwise. If you’re going to do that, I think you’re going to want the most possible protection.

One of the heroes of the book is a computer hacker. He carries out his attacks from behind a screen. He’s not exactly Rambo. Was it a challenge to create a hero out of that sort of character?

The public is realizing more and more that the people who sit behind keyboards, who know what they’re doing, and who hack their way into networks, can do enormous damage. There may be a stereotype about what that person looks like, and that stereotype may have some justification, but those people can do as much or more damage than the traditional fighter. In the Stuxnet attack on the Iranian nuclear facility, we didn’t blow it up with bombs or bullets, we blew it up with bits and bytes. And that takes a very different kind of person. The FBI director was joking the other day that he needed to hire people who smoked marijuana because the kind of people you need as hackers are just very different from the straight-laced fighters.

He faced a lot of criticism for saying that. He had to take back that statement.

That’s right, but it follows on an Air Force general saying a couple of years ago that we need to change the physical requirements for Air Force recruitment. It wasn’t important how far you could run or how much weight you could lift, since for many of the jobs all that matters was how adept you are at the keyboard.

I recall speaking to a lieutenant who had been through five deployments in Afghanistan. When I mentioned drone pilots he said, “Oh, they’re not true war fighters, between their shifts they go gambling in the Strip.” Do you agree?

There was a huge firestorm in the military following the proposal that there be a medal given to drone pilots. It was the same medal that was going to be given to hackers. I completely understand that people who spend twelve months in Afghanistan or Iraq, risking their lives, being shot at, living in wretched conditions, would think that they had sacrificed a lot more than people who sit back in the United States and play with keyboards or joysticks.

That having been said, there should be some medal that could be given to those people. I don’t want to equate the sitting back in the United States with a joystick or a keyboard with being out in the country like Iraq or Afghanistan being shot at. There should be some medal that would be offered for people who make that contribution.

And yet medals are traditionally associated with courage and bravery, and bravery doesn’t seem to fit into the picture when it comes to drones.

No, there are military awards that are given for accomplishment, not just for bravery. And there are some very significant accomplishments that people sitting at Fort Meade have achieved, to protect the lives of innocent people.

There are several references in the book to police drones, and with that the development of technology that allow drones to be made smaller. In being small, the drones offer different deadly capabilities, and pose new threats to adversaries. Are you concerned about the drones coming home?

Police in many cities are already flying helicopters, and have been for many years. There are some differences between that and the police drones. But I think that the public in general needs to be aware of the problems that will arise, and indeed are already beginning to arise, with domestic drone flight. There are safety and privacy issues that we’ve only just begun to explore.

The international proliferation of drones—that is other countries adopting and developing this technology, particularly lethal drone technology—has also received rather a lot of attention in the past couple of years.

The number of countries that now have drones is shockingly high. It went from a very small number to a very large number quickly. I think only three countries have used drones in lethal operations, but the number of countries who have them is probably in the 40s by now. The number of countries with lethal drones is probably at least a dozen. So we will see a lot more of drone attacks in the future. We have to remember that everything we do sets a precedent.

Do you think the use of drones by terrorists is a credible possibility? The FBI reportedly foiled an attempt by terrorists to use explosive-packed drones.

The FBI case is interesting because it was a sting operation. The FBI found someone who they thought wanted to be a terrorist and then suggested he should get a small commercial remotely piloted vehicle and use it to attack the Pentagon. When he said he didn’t know where to get a drone, they told him where to get it. And when he didn’t have enough money, they gave him the money. So the man was arrested more for an FBI idea than for his own idea. But it does demonstrate that the FBI is at least thinking along these lines.

There’s something about drones that captures the public imagination. The book examines that, capitalizes on it even. And yet you say that, in a sense, the drone is just an aircraft.

The phrase that has caught on is “flying killer robots.” When you think of the drone not as a remotely piloted vehicle, with a pilot, but rather as a flying killer robot, it hits a reflex in a lot people. Just as humans have had a fear of snakes from years gone by, we are likewise developing a fear as a species of the rise of the machine. We’ve all seen the Schwarzenegger movies with the killer robots: we fear that possibility, even though it’s science fiction. We wake up one day and we have the drones in the real world, drones that people describe as flying killer robots. That hits a raw nerve with a lot of people.

We all know, or at least most of us know, that they’re not robots. Yet it is also clear that they could be. The Navy, for example, has developed a drone that can fly autonomously and could be programmed to find enemy targets and attack them without any pilot being involved. You could tell the drone, “This is what an enemy ship looks like, if you see anything that looks like that, kill it.” That capability has been developed, it’s just not turned on because the current Pentagon policy is that there has to be a person in the loop. But the killer robot, the autonomous killing machine, has been invented.

What are you future writing plans now?

I have an outline for a sequel to Sting of the Drone, with some of the same characters. And I have an outline for a non-fiction book that I have been wanting to do for about six years now. It’s the kind of book that requires a lot of research.

Arthur Holland Michel is the founder and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of the Drone, an interdisciplinary research, art, and education project at Bard College.