Sarah Manguso’s latest book, Ongoingness: The End of a Diary, ostensibly about the eight-hundred-thousand-word journal she kept for twenty-five years, is in essence an act of withholding. On most pages, a few paragraphs or lines of text are surrounded by white space—precise moments suspended in the mass of formless, unrecorded time. Manguso describes how those blank spaces terrified her as a young woman. When a friend offers her a ride home from another city, she declines so she can spend the four-hour bus ride writing in her diary. At that point, she feels that recording an experience is the only way to control it, to avoid getting stuck in the experience or losing it altogether. Later, when Manguso’s son sets his blue toy dog in a booster seat and offers it a piece of his pancake, she cannot leave him to write it down, and the moment passes. Becoming a mother forces her into the present. After so many years and so many pages, Manguso has found a way to say less. I talked to her by phone.

How did you choose the title?

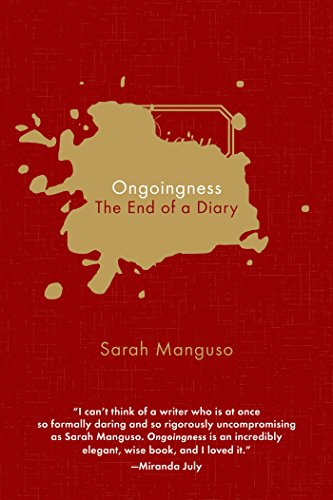

I found a note in my diary in 2010 saying that I’d begun working on the problem of ongoingness in autobiography—the idea that one can’t perceive and depict ongoing time at once. The subtitle came much later. My publisher and I came up with a short list of about fifty possibilities; in the end, it was between The End of a Diary and The End of Beginnings and Endings, which I also like, but we needed a concrete noun on the front cover.

Had you intended to write a book about keeping a diary?

My original intention was to produce a researched nonfiction book about graphomania, compulsive writing, as a way of getting out from under my own many-times-daily diary. I worked on that book for two years. Then I gave birth to my son, and time changed; the diary also changed. The book changed, too, into a document of the present moment.

Where did the compulsion to record your experiences come from?

Writing about an experience allowed me to feel that I had finished living it. If I didn’t write about it, I still felt partly contained in it. The diary provided a solace that I wouldn’t otherwise have.

You mention that you edited entries even though you didn’t intend for anyone to read them. Would you omit different things if you were writing for an audience?

No. As with my writing for publication, the diary is just an opportunity for me to attempt to write some good sentences.

Do you still keep a diary?

Yes, but it’s more compact than it used to be. The subtitle of the book is The End of a Diary not because I no longer keep a diary, but because I no longer write the diary to combat the existential anxiety of becoming trapped in time. That concern sounds insane to me now.

The book also addresses the fear that experiences become less real when we lose the person we’ve shared them with. Can you say more about that?

That concern—a narcissistic worry?—was the reason I went into psychotherapy. Not knowing whether the other half of a relationship would be kept on record somewhere—in a mind or in a document—felt unbearable.

Do you think language has the capacity to represent who we are?

We can only hope.

Did marriage and motherhood affect your sense of time?

Marriage didn’t at first, but the experience of becoming a mother did immediately.

You say that after having a child you began losing interest in the beginnings and endings of things. How did that alter your experiences?

I am no longer so troubled by the passage of time.

Is that what the book is about, ultimately—your relationship to time?

My friend Jim Richardson, a fantastic writer, sent me this deeply intelligent reading of the book: What begins as a book about time eventually becomes a book about love. As soon as I read that, I knew he was right.