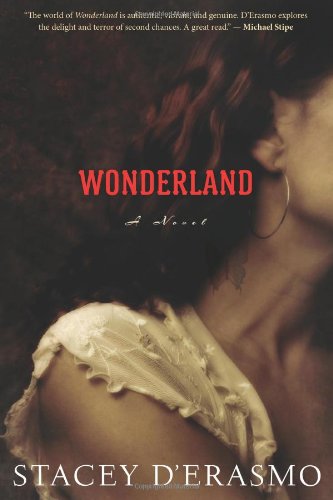

Brian Eno famously said that everyone who bought the first Velvet Underground album when it came out ended up starting a band. Someday soon, something similar could be said of Stacey D’Erasmo’s music-drenched road novel Wonderland. It’s truly an inspiring work—a master class in structure and character—and it makes you want to be a rocker and a writer. The story follows a former rock star, Anna Brundage, as she attempts a risky comeback and tours across Europe with her new band. I recently spoke with D’Erasmo about artistic ambition, the phenomenon of “dating your own characters,” and the differences between novelists and musicians.

The scenes where Anna is onstage performing music are so vivid. Did you do research to come up with your language for them?

I did research, definitely. Reading musicians’ bios, talking to musicians, going on tour with the Scissor Sisters. But I wrote most of those scenes before I had even gone on tour, and I’m not sure I ever asked a musician, point-blank, what it feels like. I drew on my intuition.

I love that the book follows Anna’s tour. Structuring it like that created a sense for me that she is running away from something. Do you think she is?

Mmmm. No, not running away, but she is busting out, do you know what I mean? You can’t be a musician in the way she is half-heartedly, or even within reasonable bounds. You have to go all in, and that’s what she’s doing. I might say “plunging” rather than “running.”

There’s a scene in the book where Anna makes a record she feels is beautiful, but then she’s summarily dropped by her record label. There was a period in the ’90s when every band I loved was dropped by their label, and then they broke up and went away, and it broke my heart. I think that’s one of the main differences between the music and publishing industries: In publishing, if a writer gets “dropped,” she keeps writing.

Yes, absolutely. We all know what’s been happening in the music industry in general, and how many extraordinary musicians have moved away from mainstream labels altogether out of frustration. But to answer your question, that’s something about working in music that is quite different, and very, very risky as compared to writing. I could write ten novels sitting in my house that never get published, and yet I’d still be writing. For a performer, if you lose the means of being heard or seen, you can’t do your art. Performers need audiences in a much more urgent way than writers do. It’s part of the high-wire act of making that kind of art.

Anna is a very sexual woman in her forties, which I think is kind of rare in fiction. She reminded me of a quote I once heard about Joni Mitchell—that she was just like a guy in that she would sleep with someone and then write a song about it. I think Dylan said that, or Crosby. Can you talk about developing Anna’s sexuality?

It’s funny, people keep asking me about that, and I’ve been a little surprised—her desire doesn’t seem that rare to me. But I think you’ve hit the mark when you say that a woman like Anna is “rare in fiction.” In life, women in their forties (like women in their twenties, or their fifties, or their thirties) have plenty of desire. Even if one somehow didn’t know any women, every website and tweet and article out there shows that. Women are appetitive, sexual beings. But in fiction, and I would say especially in literary fiction, there still exists a code whereby the appetites of male characters are the stuff of serious fiction, but female characters are taken seriously when they suffer for, are punished by, or are severely damaged by their appetites. It’s as if the only thing women can say about sex or desire that matters is that it causes pain. And, yes, desire can involve pain. But that’s only one part of it. Desire can take us many places. In that way, I think with Anna I just made a character who’s closer to life than to the sometimes punitive ideas about women and sex that reign in the literary world.

And it’s not just Anna who’s sexy. I loved Jean, the bassist, “the perfect boy whom everyone wanted and no one could have.” There’s always a boy like that in every band. He made me remember something about your fiction—you always write characters that sort of make me want to have sex with them. I fell in love with the main character in The Sky Below, too—although I wouldn’t have slept with him, for fear of catching something. Do you develop crushes on your characters as you’re writing them, too?

Thank you. And, well, that could really work out, right? You just keep yourself company by dating your own characters. Might be we all do that a little, right? Invent the people we’re dating? Anyway, I think what you’re picking up on might be the way in which fiction brings us into this extraordinary closeness with characters. Forster talks about this in Aspects of the Novel, that we get closer to characters in fiction, to their secret lives, than we ever can to real people. What can I say? Reading and writing are sexy activities. Spread the word.

Okay, last two questions! One of them is silly.

Great. I like silly.

So, I imagine that you have a secret literary rock band that you play in. Maybe you on guitar, Joan Didion on bass, Michael Cunningham on drums. That’s my current dream lineup for the Stacey D’Erasmo Experience. What’s yours?

Ha! Elizabeth Bowen on guitar—imagine?—Didion on bass, Cunningham on drums, and—hey, it’s my fantasy, right? So I’ll be lead singer. Because also in this fantasy, not only does Bowen come back to life, but I can sing. The latter is less likely by far.

There’s a moving moment in the book where Anna takes the stage and makes eye contact with a young man in the audience, who looks up at her “beseechingly.” Are there moments like that for you with your writing career—where you know you’ve made this one-on-one connection?

That instantaneousness is actually the kind of moment writers specifically don’t get that often. We write in private, and are read in privacies to which we don’t have access. But at my Housing Works event last night, when Rachael Yamagata was playing the song that she said was her interpretation of the relationship between Anna and Simon, Anna’s married lover, that felt like the one-to-one connection that you’re talking about. And it was thrilling.

Gee Henry is a freelance writer who lives in Manhattan.