Although it sounds like the name of a sequel, LaserWriter II is the debut novel of writer and designer Tamara Shopsin; it takes its name from a laser printer manufactured by Apple in the early 1990s. The mechanics of printing are a formal concern throughout the book, which is divided by surprising page breaks and pixelated illustrations, as well its central plot fixture: Shopsin follows Claire, a young New Yorker with anarchist leanings, through her stint as a printer technician at Tekserve, a computer-repair shop that operated on West 23rd Street until 2016. Between shifts spent laboring over paper sensors and I/O boards, Claire quietly observes her coworkers, delegates of various ’90s countercultures who are united by their fascination with desktop publishing. Shopsin makes Tekserve sound about as utopian as a retail space can be, but Claire and her colleagues find echoes of bleaker political-economic shifts in their work: fixing a broken LaserJet at one point, a technician named Joel notes that “the fan (much like capitalism) has a design flaw that makes it eventually fail.” Set just before the dot-com crash began to really loom and filled with great period details (everyone is constantly drinking Snapple), LaserWriter II registers a sweet spot in the history of personal computing when the industry seemed built primarily to “help people make poetry and do their taxes.”

LISA BORST: LaserWriter II is a workplace novel that takes place at a now-shuttered business called Tekserve. Would you mind giving a quick overview of the what the shop was?

TAMARA SHOPSIN: If you lived in New York in the ’90s and you had a Macintosh, you ended up at Tekserve and your world was a better place. It was, at its bones, a computer repair shop in the Flatiron District, but it was much more. It was weird, and it had soul. It was funky, magical, and beloved by nearly everyone who went there. I worked there for maybe three months in the late ’90s.

Your last book, Arbitrary Stupid Goal, is set mostly in Greenwich Village at the original location of Shopsin’s, your family’s restaurant—another weird, offbeat business that seems like it’s so customer friendly that it’s, like, allergic to making money.

I would say my family is allergic to making money. Growing up in the restaurant, one of my dad’s golden rules was, “We don’t serve assholes.” This was gospel, and assholes were kicked out on the hour. Which is very different from Tekserve, where assholes and squeaky wheels were given special treatment and extra kindness. But there is definitely crossover between my family restaurant and Tekserve. Both spots felt outside of time, and the relationships with customers went way beyond the realm of commerce. I felt at home at Tekserve from the start: both places were decorated like an old general store, with wooden radios and tin signs, both came at retail from counterculture. At the restaurant, my mom and dad sliced meat in a meat slicer, but they also had a community bookshelf. Tekserve donated its service to almost any nonprofit that asked.

Did the work experiences feel analogous for you at all?

Not really. Working at the restaurant was very different because I sometimes wore pajamas while I was doing it. It was my home and my core. I work there to this day. It’s a constantly changing thing, but is still a huge part of my life. Tekserve was a much littler part. My decision to focus on it in this book came less because Tekserve was vital to me, but because I felt it was vital to New York, and to the history of Macintosh. The only thing that really felt analogous was that at both shops, when you interacted with customers it wasn’t about the money. The goal at Tekserve was to help people, truly.

Claire, the protagonist of LaserWriter II, works alongside this amazing cast of artists and freeform radio engineers at Tekserve, whose character sketches unfold in parallel to her own narrative arc. How do you see Claire’s role in the book?

Claire is for sure an introvert. I’d say she has two missions. The big one is to pull back the curtain on Tekserve and give the reader a tour, and her coworkers are key to that tour. They are what made Tekserve hum. (Many of the characters in the book are based on real Teks. For the most part, their backstories are real.) Claire’s other mission is smaller: to guide herself through Tekserve.

I’m interested in how subcultures operate in the novel—how they exist alongside commercialism or corporatism. Your novel plots Apple’s own larger shift toward market domination, coming out of an era when personal computing positioned itself as the territory of hippies and dropouts. What was important about that moment to you?

There was just a different idea of what Mac was back then. You loved your computer, you had your printer for like fifteen years, and it was made to last. And there were hidden jokes in the Finder menu. The sounds the computer made had funny names. It felt like the products had personality and spunk. You felt bonded to people that had the same model of computer. In the book, I wanted to lay out what that smaller, early computer culture was like. And the best way to do that for me was to document what Tekserve was and what it meant. That was really my impetus for this project.

The book suggests a kind of rhyme between gentrification, at the urban scale, and planned obsolescence, at the level of personal computing—two top-down processes that render everything more precarious and replaceable and expensive. Are you worried about New York?

I’m not worried about New York now; I was when I wrote this book. It felt like New York was on warp speed to becoming a boring, unlivable city, and the things I loved were disappearing. One of my ways of dealing with that was to write this book. To try and preserve something I loved that disappeared. But I think the pandemic put the brakes on this lemming march off the cliff. Tekserve closed back in 2016 because rent was doubling and there was a Best Buy down the block and gleaming Apple stores a subway stop away. Sometimes the lil’ guy isn’t meant to beat Goliath. But it seems like right now the lil’ guy has sway in New York. After being in New York during the pandemic and seeing the way the whole city responded—and seeing people who left to shelter elsewhere coming back with a renewed appreciation for how wonderful it is—I have a sort of Care Bear‑outlook that everyone is doing their best not to fuck up NYC.

Are there still places in the city that feel special to you in the way that Tekserve did?

Oh yeah. New York is full of them. Many are disappearing, but new ones are being added. I have restaurants, bookstores, cultural institutions, and public parks tucked away all over the city and I visit them regularly. My husband gets his camera repaired at Nippon Photoclinic in Midtown, which is a very different scene than Tekserve, much more V-neck sweater, but special in its own way. Around the block from Nippon is the NYPL Picture Collection (that just got saved!) an amazing place that is an algorithm-less, IRL image search engine. Downtown, there’s Anthology Film Archives, which projects celluloid and preserves films of freak talents like Taylor Mead. The film-preservation arm of Anthology is a gift to the future. And there’s a new record store down the block from Anthology called Ergot Records that I haven’t even been to yet.

What about online? The novel catches a moment when people are using proto-internet networks to find community. Are there places on the internet that feel that way to you now?

Stack Overflow is, for me, the most utopian place on the internet. It’s a forum where you can post questions, mostly about computer programming, and then a stranger will answer you. Actually, multiple strangers answer, with not only explanations, but also snippets of code that each stranger refines till it is a perfect poem of JavaScript or CSS. You can just copy and paste the exact snippet of code that is, like, the answer. I don’t really know how to code—I know how to use Stack Overflow. The internet is amazing at building the internet.

But there are large swaths of the internet I avoid. I don’t use Twitter. I use a plugin called LeechBlock that limits my time on sites that I get sucked into. The rise of online retailing and how it hurts brick-and-mortar stores is especially terrifying to me, as well as the whole telecommuting thing. I get all the positives in it, but I’m not optimistic.

LaserWriter II is written in the sort of fragmentary mode that critics sometimes compare to scrolling on social media—but in fact, for a book about computers, it’s really not about the internet at all. I don’t think you even mention it until page 160 or something, which is very refreshing! Where does that prose style come from, for you?

Right, the book is definitely not about the internet! Part of the joy is about existing in a time when the internet was a tiny speck.

About the prose—I didn’t go to writing school. I’m a designer and illustrator. When I wrote my first book, Mumbai New York Scranton, I figured out my writing voice, and I’ve found that the fragmentary mode is just how I write. I do feel very strongly about it. If somebody tries to take out the white space, I will be a total asshole and make them give me an extra signature rather than change the flow. The fragments are not meant to read like a social-media scroll. I hope people are filling in the white space, building the world with me. I leave gaps when I draw, too. I don’t know if “compression” is the right word for the process, but I’m trying to get the most out of the least.

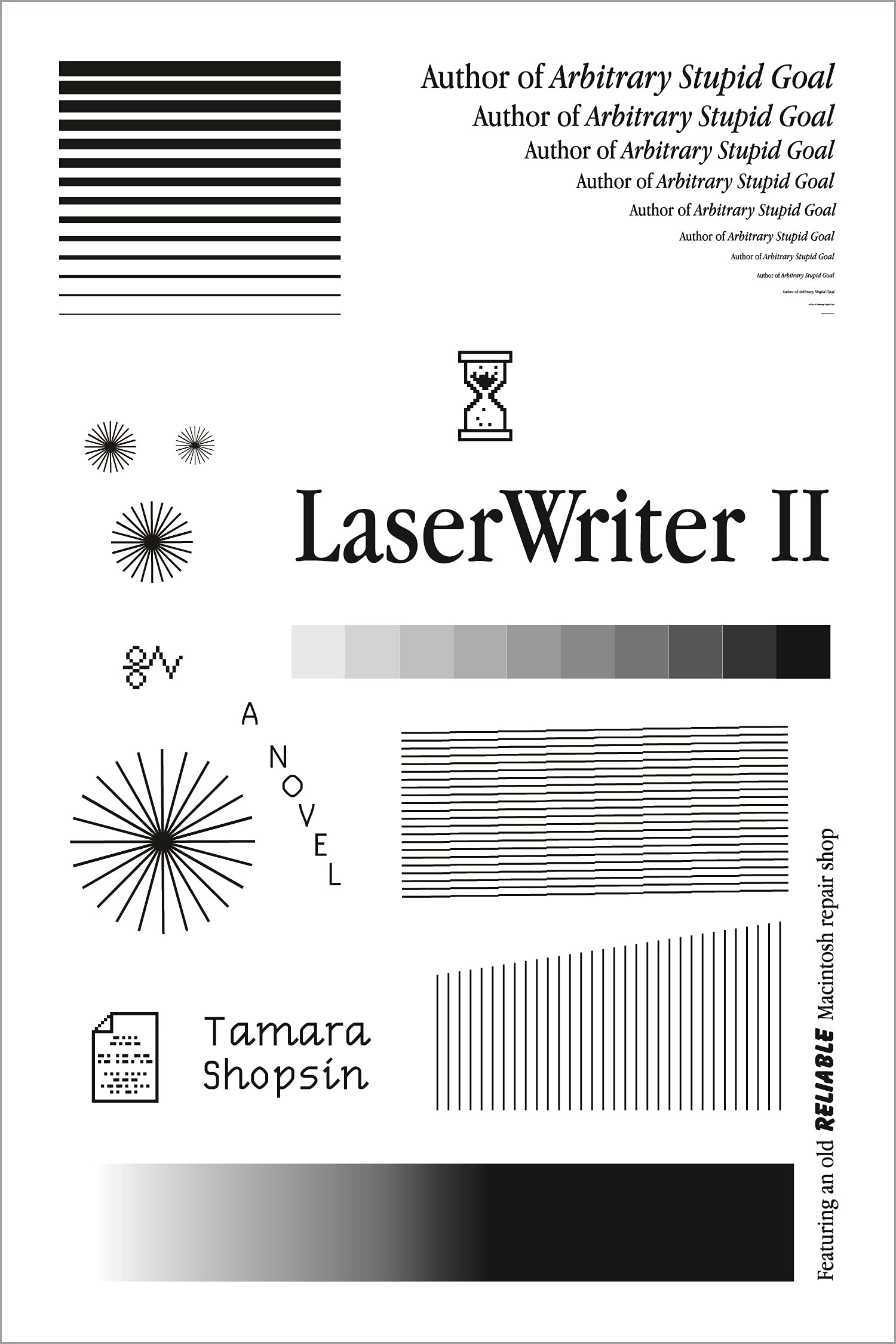

How do you see the relationship between your work as a designer and your writing? You designed the cover art for this novel, which I love. It really looks nothing like other books.

It relates to what I was trying to get at with “compression.” When I illustrate, I am basically distilling—turning a complex idea into a simple form—and that’s also the way I try to write. And my influences are from all over and they touch everything, so the designers affect my writing and writers affect my illustration. Playful artists and design thinkers like Bruno Munari, Charles and Ray Eames, Corita Kent, and Saul Steinberg. I love comedians especially: Ernie Kovacs, Gracie Allen, Harpo Marx, Richard Pryor, Andy Kaufman, Albert Brooks, Fran Lebowitz, and early Whoopi Goldberg. And writers that make me laugh, like Robert Walser, Sergei Dovlatov, and Flannery O’Connor. Small perfect books, such as: True Grit by Charles Portis and Mount Analogue by René Daumal.

But illustration and writing are also opposites in a way. In illustration, it’s always hard to find the idea (the image, the symbol, the hook). “Hard” is an understatement, but once I find that idea, it’s easy to render, because it dictates the form. Writing is the reverse: I find the idea easily, I know what I want to write about, but rendering it is a struggle.

Lisa Borst works at n+1.