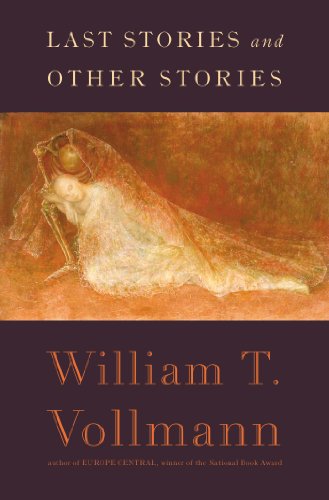

In 1994, as William Vollmann traveled by car from Split to Sarajevo with two fellow reporters—one of them a friend he’d known since high school—an explosion or possibly a sniper killed his two companions. Later, while reporting on the Siege of Sarajevo, Vollmann was offered journalistic access to an important Bosnian military leader if he was willing to murder a prisoner of war as a show of loyalty—an opportunity he turned down. Fictional treatments of these real-life horrors open Vollmann’s Last Stories and Other Stories, a collection that veers from realistic to supernatural representations of death, from reportage-like writing to the ghost story. In nineteenth-century Bohemia, a man’s wife lives on as a vrykolakas—Greek folklore’s equivalent of a vampire—contending with her husband’s wandering eye. In contemporary Veracruz, a bookish and depressive Ph.D. candidate studying folklore falls in love with an incarnation of La Llorona—a woman who, according to Latin American legend, has murdered her children, but who, in Vollmann’s representation, becomes the incarnation of the plagues that have killed vast numbers of Mexico’s indigenous population. True to Vollmann’s expansive sense of history and place, the stories span three-hundred years and four continents, including stops in Lillehammer, Tokyo, and Toronto.

Though this is his first book of fiction since his National Book Award–winning novel, Europe Central (2005), Vollmann—always prolific—has, in the meantime, published non-fiction books on poverty, California agriculture, freight-train hopping, Noh theater, and in The Book of Dolores, a book of photographs of himself dressed as a woman. When I spoke with Vollmann, he had just returned from West Virginia, where he’d been researching mining for a nonfiction book about climate change, fossil fuels, and nuclear energy. For this latest project, he’s been learning to use equipment to test water quality and radiation levels. Vollmann also made headlines in non-literary circles recently when he learned through a Freedom of Information Act request for his FBI file that he’d been a suspect in the Unabomber case.

You’ve taken on a lot of projects and adventures in order to broaden the experience you bring to your writing. Most of them have been what we might traditionally think of as masculine activities. How did the Dolores project feel different from those? How did friends and the public react to it differently?

It was a little embarrassing and humiliating, for sure. Just recently some journalist was saying, “Bill, speaking as your friend, why Dolores?” Particularly in my generation, and the one older than mine, there’s definitely a relation between gender and class, and so when a man dresses as or acts as a woman it can perceived as a step down, and that makes some people very uncomfortable. I also think that most heterosexual men—whether they would admit it or not—can’t help but check out almost every woman walking down the street and think: “Is this woman desirable? Would I enjoy touching her or sleeping with her?” and then the woman passes by and she’s immediately forgotten because here’s another one. So, for me it was interesting to experience a little of that objectification and also to conduct whatever thought experiments I could: What would it be like to be a woman? What would it be like to be a beautiful woman? Dolores would always think that she looked pretty good and she’d always be quite surprised when these pictures were taken of her and she didn’t really look all that good.

It’s been an interesting project. I got a lot out of it, including just learning what my face really was like. As a man, I’ve never really cared much if my face is stubbly or if my hair is too long or not combed. What’s the difference? Ever since I was a teenage boy, I’ve always thought that if people judge me poorly because of my appearance, then I don’t really have much use for them. But when I was trying to be Dolores, it was all about how well I could look the way I was trying to look, how well I could pass. So for me, it was fun, just like a kid playing dress-up and fortunately the stakes were low—not completely low—because I did publish the book, and so now and again I hear some things that make me uncomfortable or humiliated, but I’m reminded that, in a way, that is what I set out to do.

You just returned from a trip to West Virginia. How did it go?

I’m trying to learn about the culture of mining and the whole debate over coal versus nuclear, as well as people’s opinions on climate change. I haven’t been able to get into a coal mine yet. The big guys have no incentive to let me in, since I might cause them trouble, and the little guys run these dangerous fly-by-night operations.

I had my pancake frisker [a type of Geiger counter] with me and it turned out that the most radioactive thing I could find on the ground there was a huge granite slab in front of the courthouse with the ten commandments on it. So that made me happy.

In Europe Central, you wrote about artists and writers who were tracked and scrutinized by their governments. In your book, the surveillance agents are cast as literary critics looking for hidden meanings in the work. You recently wrote in Harper’s Magazine about learning that the FBI once considered you a Unabomber suspect. What did you learn from finding out that you, like your characters, and your work, had been the subject of the government’s analysis?

It was entertaining to me to note the FBI’s efforts at literary analysis. I can’t say that I was very impressed. I think they would have failed a comparative-literature class. They made a few mistakes. For example, they claimed I must be supporting subversion and anti-American activity because one of my books set in seventeenth-century Canada seemed, in their view—which was wrong—to tilt toward the Iroquois. Of course, I don’t see what a book set in Canada before the US ever existed could possibly prove about my terrorist sympathies, but anyway, I kind of enjoyed getting a look at their attempts.

Have you had any contact with the people who you know who spoke to the FBI about you as a potential Unabomber suspect?

I can’t know for sure who it was. In one case, I’m pretty sure. In another, I’m somewhat sure. I don’t hold it against either one of them. The Unabomber was doing a bad thing. They were doing what they thought they had to do. Just as Ted Kaczynski’s brother did what he had to do and turned in his brother. The people who spoke to the FBI about me were wrong: I wasn’t the Unabomber, but I can’t blame them for being worried and doing their best to try to protect others.

With Last Stories, you’ve written a book about ghosts after writing for many years about the nature of violence. The book’s structure—with fictional versions of your war correspondence at the start, followed by ever more supernatural tales—hints at ghosts as a representation of PTSD and the double meaning of being “haunted.” How are those two concepts linked for you?

I think for most of us death is not something to be welcomed. It’s a frightening thing. It’s an awful thing when death takes people that we know, or even when we happen to see it take strangers. We know that death will devour us sooner or later. So I imagine that the older we get, and the more experience we have of death, the more likely we are to experience some of the symptoms of PTSD. The great expressionist artist Kathe Kollwitz, who is a character in my novel Europe Central, always said that as she got closer to death, it lost much of its terror for her. She started making drawings of herself turning around with death putting his hand on her shoulder as a friend. Some of the stories in the collection treat death in a negative way and others are a little bit more nuanced. I’m sure I will find death quite scary and unpleasant. It’s good to give it a little bit of thought all the time, but not too much.

When you were nine years old, you were asked to watch your six-year-old sister while the two of you were playing beside a stream. During that time, your sister fell in and drowned. You’ve said that afterward you had nightmares of being pursued by skeletons. It’s hard not to see a reflection of that event and its aftereffects in these stories. How did that influence your writing and this collection in particular?

As a result of that experience and the many years when I was greatly oppressed by it, I wrote these stories knowing something about where this dark place might be. Now that I have—to an extent—come to terms with it, I can go back to those dark places on an experimental basis as long as I need to while I’m writing the story, but I don’t have to fear that it’s going to be some horrible thing that’s going to damage me. Writing Last Stories, I was able to say, “Well, all right, I’m 54 years old now and I get it that I’m going to be in the grave sooner or later, so what’s the big deal?” I can sort of play with that stuff and it doesn’t have to give me nightmares.

Would you live forever if you could?

I don’t feel terrible about the idea of nonexistence. The big phobia in Last Stories is the idea of eternal consciousness within the dead corpse. One point Last Stories makes is if that were the case, it might not be much different from living forever. Either way you have to accept whatever comes along.