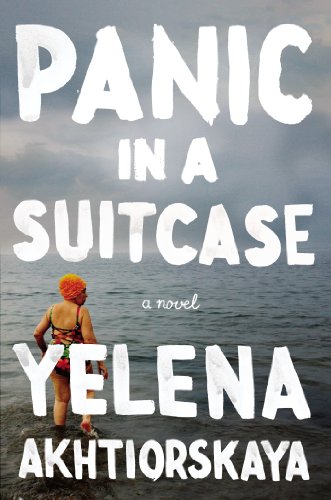

I met Yelena Akhtiorskaya in the Columbia MFA program, and soon after edited her first published stories, at n+1 magazine. These were portraits of Russian immigrants who failed to fully embrace their new country; they often dreamed about returning, or at least about taking a vacation. Akhtiorskaya’s layered first novel, Panic in a Suitcase, out last month from Riverhead, is also about ambivalent newcomers to the United States. The Nasmerstov family tries to persuade its most outsized member, the poet Pasha, to finally relocate from Odessa, as its youngest member, Frida, considers flying the coop to Ukraine. Most extraordinary about the novel is the language, which can swoop in and out of the consciousnesses of multiple characters in the space of a sentence. We spoke about Akhtiorskaya’s writing early this summer at her apartment on the Upper West Side.

When did you start writing about Brighton Beach?

Not until graduate school. For the longest time, I thought that you could not mention the word “Russian” in a story, you could not mention a neighborhood, you could not mention any specific location, ethnicity, nationality.

Why did you think that?

Because fiction had to be universal and speak to everybody on the most basic human level, so why would I write about Russian characters, who would only make it not timeless and universal? How could I possibly mention Brooklyn, let alone Brighton Beach?

How did you get out of this?

I would give my stories to my boyfriend at the time, and he would say, “This character does not make sense because she’s so clearly Russian from Brighton Beach, but you have her floating in nowhere land.” Now I’m afraid that I’ve swung too far in the other direction.

What was that first thing you wrote about Brighton in grad school?

It was a novel called My Building. It was actually two novellas, and I don’t know if I want to talk about it because maybe I’ll recycle some of that material. But it was about my building—I’m obsessed with the building my parents live in.

What about it are you obsessed with?

There are a lot of characters that need to be institutionalized. We don’t have a doorman, but we have a Georgian man who smokes nonstop and mutters to himself, sometimes screams obscenities at the top of his lungs, and stands outside of the building at all hours of the day and night and lets you in if he likes you, which is good for our family because he likes us and we always forget our keys. There’s a grotesque family with a sex slave from Ukraine, poor girl. This family doesn’t pay their maintenance and is suing the building and the building is suing them. Everybody’s suing everybody. They’re in court all the time. My mother is on the board, which is trying to keep the building from falling into bankruptcy. It was also hit really hard by Hurricane Sandy.

Are other buildings in Brighton like this?

I’m not sure what’s going on in other buildings. My guess it that we’ve got more bile and lawsuits and—fighting. At the co-op meetings, people get bloody.

So we won’t talk about the specifics of the book, but broadly speaking it was two novellas about two people living in the building.

One of them was about a man who owns a sketchy watch store on Kings Highway and drinks himself into a stupor, so his mother has to come and try to save him. And the other was about a young woman who walks out of her job one day and never goes back and falls into an aimless way of being. The woman lives in the apartment directly above the man.

Were there any books with a two-part structure that you had in mind as you were writing?

I’ve always loved Franny and Zooey, in which the two characters are also the two parts of the book. But I’m coming to terms with the fact that my brain probably just works in two parts.

I wanted to ask if you intended to carry that structure over to this new book.

I didn’t. That was the reason the first one died.

You wrote My Building in grad school and you sent it out, but you weren’t able to sell it.

Indeed. The trauma made me not want to go back to the document, and luckily the computer on which the document exists died and I’ve been meaning to take it to the Apple store for almost a year now to retrieve my documents from it but failing to do so. I like to keep thinking that it could’ve been a book. I don’t look back and say, “Oh my God, what the hell was I thinking?” But the reason it failed was its two-part structure. Everybody said, “This isn’t a novel.” The two characters didn’t fall in love, or interact whatsoever.

Was it hard for you to write after that?

It was hard when it was getting rejected. I just wanted to snap my fingers and be in a better place. That was when I was working at the Strand, shelving books in the fiction department, and I decided to quit and move to New Orleans, where a bunch of my high school friends were at the time. New Orleans is a wonderful city but I didn’t last long there, it’s too sunny and joyful—in half a year I was back in New York. Anyway, I just abandoned that first project, made a clean break, didn’t think twice about it. It must’ve been a strong survival instinct kicking in, because usually I dwell on every failure. My usual rule is the more something is a failure, the more time and energy I will invest in it. But I started writing this book right away.

Did you think of this new book as having a two-part structure from the beginning?

Originally, I set out to write a traditional, expansive, linear book spanning smoothly across the generations, basically this very masculine thing. But the strange thing about writing is that you’re finding out what’s there and what’s not there, and eventually I had to face that there was no middle. The middle was empty.

How did you decide on the Pasha character, the uncle who stays in Odessa?

I wanted to have a character who is conflicted about immigrating and ultimately decides to remain in the old country, because I’ve always been interested in how those decisions get made and what the consequences are. And then I could have the chance to show Odessa in all its glory—although I’m not sure I really did that. And the character is an uncle because I have an uncle who stayed in Odessa.

Has he read the book?

Not yet. The whole family is a bit hesitant to give it to him. Even though I’m sure he’ll see that the character isn’t him, there are similarities, so it could be a bit eerie.

I think he’s noticed that my mom, his sister, has been avoiding giving him the book. My mom was just in Odessa, and his wife said, “Is it really terrible, what she wrote about us?” But it’s not terrible.

You’ve been back, right?

Yes, several times. It’s often an unsatisfactory experience that I want to repeat again instantly, like scratching an itch. It’s hard to wade through the emotions and get to the actual moment. I feel a bit like a fraud, being there. I have all these feelings for the city, but for my parents those feelings are very authentic, they have memories tied to every corner, and then I wonder how can I make a claim to this place. Whenever I’m there, except for once when I didn’t go with my parents, I become extra stiff and shy. It’s like there’s something perpetually caught in my throat.

Was it different when you went without them?

It was better, but that’s mainly because that time I went for longer—a month—and tried to just live there for a moment, be quiet there. It got to be peaceful and natural and it felt like I could somehow try to make this my place.

Do you think your family wanted you to write about Brighton?

For a long time my mom would say to me, “Why can’t you go back to what you were writing before? I really loved your stories in high school.” Which is when I wrote science fiction.

I remember something funny your mom said about the first story you published in n+1. She said, “Did they pay you for that?” You probably said, “Not very much,” and she said, “That’s good, because you owe me half of it.”

It’s probably more than that. Because I’ll fall into a depression and my mom knows what the treatment is, and that’s gossip. She administers it like an injection. She gives it to me because she knows that’s what she has and that’s what I need. I don’t actually have the wherewithal to keep in touch with people but I am dying to know everything they’re up to.

Do you think she realized you were going to write about it?

After it happened a few times she resolved to cut me off from this information, but what would we talk about then? I think she has to not think about the fact that absolutely everything she says or does is liable to become a story. It actually adds an extra spice to our interactions—an element of danger.

Carla Blumenkranz is a senior web editor at the New Yorker and a contributing editor to n+1.