With a year of lockdown and a year at home, what’s helping you stay in what you’ve described as the “underwater” imaginative space of writing, and what’s making it harder?

I’m on sabbatical this year, and made a decision, even before the pandemic, that I was going to use it as an opportunity to do nothing. I’ve more or less worked full-time since I graduated from high school, and as you know, if you’re a writer, whatever you do for a living you always feel you have another full-time job on top of that. So I decided that I was going to spend this year not writing but experiencing what it is to be alive and to notice what it feels like to be alive. I know, I can’t even believe how that sounds, but I’m saying it anyway.

Do you feel like you’ve been able to do nothing? I read a book last year, How to Do Nothing—it’s hard to figure out how to do that.

I read that book by Jenny Odell, and it was so inspiring, filled with birds and silence and landscape and ideas. The change that I’m looking for is not external, it’s internal. In the same way that with writing you have to go quiet in order to let yourself be bored, and to move through certain states, before you arrive at the imaginative place, I think I need to do a version of that same thing in order to figure out where I want my life to go next. Thus my year of living emptily.

I can relate to this so much. I tried to come up with a new routine for myself starting in January where I don’t check my email or check anything until noon.

If you can hold off till noon, it’s clarifying, right? Because everything on the screen is about absorbing other people’s thoughts, and it’s great in a way, and it feels engaging in the moment, but then where is there time or space for you own thoughts? I say this to anyone who is reading this interview right now: maybe you don’t need to hear from me right now in this moment, because maybe your own thoughts are more interesting than mine.

With my own writing lately, I always want things to be finished when what they really need is more time, and more of the quiet kind of thinking time that you were just describing. Sometimes months, sometimes years of that time. What can you tell me about writing and patience?

I have a lot of patience for just waiting, waiting for more knowledge, waiting to understand more about the world. When I’m inside a piece that I’m working on, I don’t want it to end, because I get comfort from knowing when I get up in the morning exactly what’s ahead. That when I finally sit down to write that I’m going to this place where I’m settled in and understand the landscape and the people, and understand my own place in the story that’s unfolding. Finishing something is a thrill, but it also feels like, oh no, now what will I do.

My process is slow and cumulative, it’s not about revising as much as it’s about accumulating sentences, one after another. I see them as interlocking, like Legos or some kind of puzzle, where to go back and take out a sentence just doesn’t work, because I would have to dismantle everything all the way back to that sentence. So I do the revising in my head, before it goes down. It’s why some of those pieces in that book were in process for twenty years. You make a mistake and you have to figure out how to make it not a mistake as you go along. In “The Tomb of Wrestling” I referred to a turtle as an amphibian on page one and then had to figure out how to work the mistake into the story before the end.

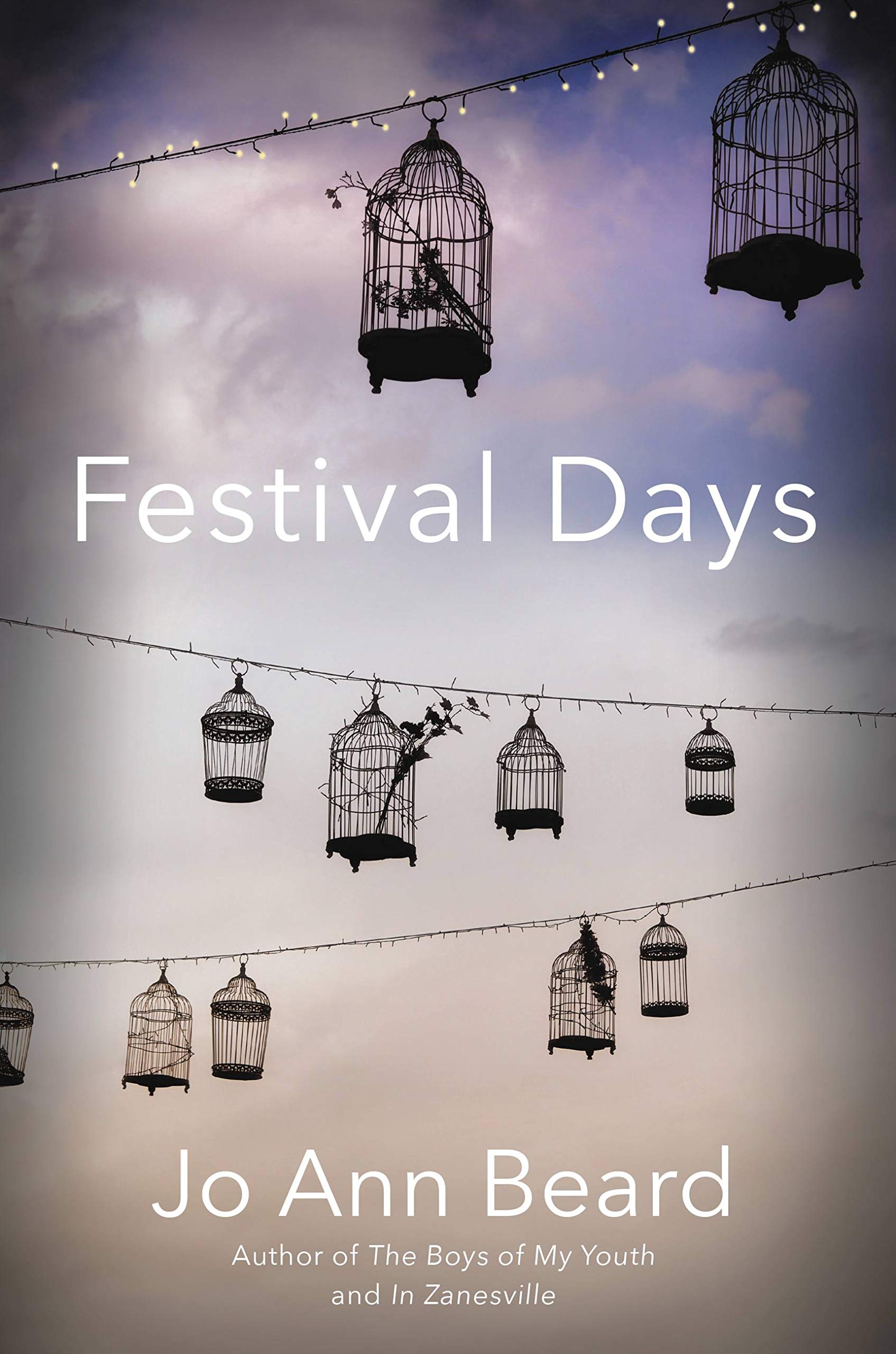

When I read the essays in Festival Days I feel nestled in this second-to-second unfolding of consciousness. Yours or someone else’s, sometimes even an animal’s. What made you realize that you could use this interior material for essays?

I first wanted to be a fiction writer, but my life was in Iowa City and I couldn’t get into the Writer’s Workshop. After several rejection cycles, the director finally called me into his office and told me it wasn’t going to happen. Which, fair enough. But then Julene Bair, a writing friend of mine who was studying both creative nonfiction and fiction, suggested I take my autobiographical stories and apply to the nonfiction program. They admitted me, and because it was an essay program, ever after I tend to think of myself as an essayist.

I was lucky to have been rejected so definitively early on, because of course it teaches you something really important about your own work and about how you have to understand who you are as a writer and what your work is. You cannot depend on somebody else to tell you that.

I’m rereading your novel right now, and it’s a delight, and I wonder: What was different about writing In Zanesville versus writing the essays in Festival Days that come from your own life or other real people’s lives?

It feels like the same thing to me, or anyway it did while I was writing In Zanesville. By the time I was done with that book I had somehow convinced myself that it was really a memoir. It was like all this really happened, though it hadn’t. But because I imagined it all for myself, I somehow felt that I had experienced it. I wasn’t going around saying this is nonfiction, but I was going around feeling like it was nonfiction, because I had lodged it in my memory by visualizing it. So, the novel felt like a memoir, and memoir feels like fiction to me. It’s like there’s a membrane between the two in my mind, but it’s permeable.

I agree. Writing about my own life feels like a very fictional enterprise.

It’s not the way we experience the world, that’s the way we write the world. In the moment, you were just having the experience, but later, in the writing of it, you must take that experience and force it to mean something (or on our better days, allow it to mean something). It’s interesting, and difficult, but no more difficult than any other genre. Poetry, for instance. Or painting.

I feel this too, that there’s something more interesting to me as a writer when the subject is quote unquote real. You write about real people in your own life, your friends like Kathy and Mary, your relationships, and some pretty painful-sounding breakups in this book. What’s your approach to writing about real people who you know who are a part of your life? Do you let everyone read everything before it goes out?

Yes I do, for the most part. And in the same way that I don’t reveal things about myself that are private, I will change things that others don’t want to have revealed. It’s a negotiation, but one that only takes place in my mind—I have always immediately said yes to anything anyone specifically asked to have changed.

Do you ever miss making visual art?

I still like to draw, but mostly just when I happen to have a pen in my hand. Then a dog will emerge, or a cigarette or a book of matches or one of the other things I long for. My version of painting now is writing. It’s easier.

Do you think it’s feeding something similar, like a need to recreate the world or document the world?

I completely do. I completely think it’s the same thing—it even feels the same way while I’m doing it. You think you might know where you’re going, but then what you put down begins to inform what you’re thinking and seeing, and it begins to change and you end up following what you’re making instead of leading, which is how I like to write, too.

In the title essay, the newest essay in the collection, you begin with the paint colors on the walls of a room in Arizona and move associatively to a hotel in India where you stayed with a friend who was dying of cancer. Was the connection between the colors what sparked the essay?

I was in Tucson in a rental house with Mary where we planned to write over spring break. The first morning we sat down at either end of a big table, with our hike ahead of us in the afternoon, and it was the first sentence I wrote. I looked around and that’s what I saw—these incredibly garish walls. At that point in my writing life everything was taking forever and my work was beginning to feel sort of cramped and dead. I was trying to loosen up and just let the first sentence that came to my mind be the first sentence, and then the next and the next. All that time with Mary when we were in the desert, and then when we were on opposite sides of the country, and then a year later we went back to the same desert and the same table, and it continued to unfurl. It was fun, because of course there were saguaro cactuses watching over our shoulders.

I can feel that as a reader, because there are many unexpected movements and connections that you make but they so clearly follow a certain train of thought that you’re on. It almost feels like being on a ride or something, it’s really thrilling to read.

When I came back from my trip I showed the pages that I had to a friend, David Hollander, and he’s really a good reader of work in process, and his advice to me was to keep going and trust the process. What I trusted was David, more than the process, but it’s good to have that, a writing friend who urges you to go forward even if the piece is a bit incoherent. And maybe it wouldn’t work out, and maybe nobody would understand what I was writing, but in the end, I would still have made my own sense of that experience. And that might be good enough. It is good enough, actually. It has to be.

What else is there, really?

Exactly. You write your story, you try to write it in enough vivid detail that the details will somehow bring forth some kind of meaning that you didn’t know was there, and then your life has meaning. And your life, the things that happen to you, make a certain kind of sense.

Jenn Shapland is the author of My Autobiography of Carson McCullers (Tin House, 2020), which was a finalist for the National Book Award.