“I was talking with my therapist today,” my girlfriend tells me. “I deny myself pleasure,” she says, with wistful resignation.

Midforties, attractive, relationships but never the white dress (“divorces without the wedding,” she calls them), my girlfriend has enticing men circling the nest—the Elvis look-alike Yugoslavian sailor, the Richard Gere look-alike Italian (“former”) porn star. Doesn’t she sleep with them? Or at least masturbate?

“So,” I venture innocently, “like, er, what would be an example of depriving yourself of pleasure?”

“Well,” she says, “like the other day, I was in the supermarket and I bought

the $2.19 toilet cleaner instead of the $2.99 one that I really like that smells like lavender.” After making a quick mental note of the name of the good stuff, I offer my sympathies.

Toilets, cleaning, and female pleasure: My friend is in Laura Kipnis territory.

Kipnis is the feisty author of Against Love: A Polemic (2003), a witty, well-argued rant against the trials, tribulations, and—lest one forget—virtual impossibility of monogamy. Kipnis covered the ins and outs—social, emotional, biological, ethical—of adultery. Her conclusion? Go for it. Besides, you probably will anyway. We are, after all, not one of the 3 percent of mammal species that are naturally monogamous, and now, with genetic testing, it looks like even female birds can be two-nesting sluts. Tweet-tweet.

Kipnis doesn’t think much of love either, calling it “both intoxicating and delusional, but in the end, toxic: an extended exercise in self-deception.” On the other hand, she suggests, “a citizenry who fucked in lieu of shopping would soon bring the entire economy grinding to a standstill.” Such a society does in fact exist: the lascivious little bonobos of the Congo. Genetically, we are 98 percent like the bonobos—and now we know what that 2 percent discrepancy entails: Retail. (And tails.)

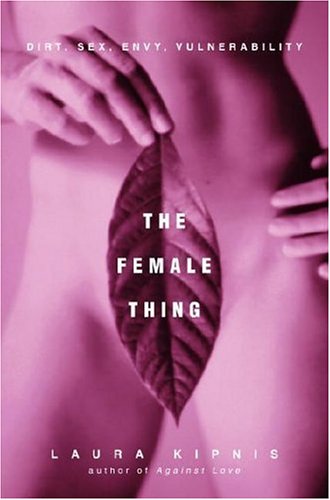

Kipnis is back with a new book of essays titled The Female Thing: Dirt, Sex, Envy, Vulnerability. While these four pieces appear more like a set of extended footnotes to Against Love than a book of their own, they nevertheless offer more of the relentless Kipnis POV, a perspective, she admits, that is all hers. God help us.

In The Female Thing, Kipnis takes on, well, you know, the “female thing.” A brief survey of my local Starbucks reveals that men think that means “the clit” or, as a married man put it more delicately, “the crux, you know, of her legs.” Women, however, regard “the female thing” as the whole thing—the entire psycho-sexual-intellectual-spiritual-hormonal insanity of being a woman. As in Against Love, Kipnis offers no answers but does a Derrida on the female situation and leaves us to sort out the awful mess.

Let’s start with what Kipnis, in a wonderful phrase, terms the “vagina-clitoris fiasco”—”a cruel combo of anatomical inheritance and sexual inhibition for the gal set; a nature-culture one-two punch.” What was the Big Guy thinking when he designed male anatomy to combine pleasure and procreation in the same place while leaving women to struggle with that half inch between their pleasure, a man’s, and survival of the species? It might as well be a million miles for all the trouble it has caused. One need go no further, so to speak, to find the source of that underappreciated, much-maligned female talent called masochism. What is the mystery here? Women are biologically designed to experience frustration.

According to Kipnis’s research, as many as 58 percent of women “don’t consistently have orgasms.” She calls female sexual pleasure “one of human history’s ongoing snaggles.” A snaggle? It’s a genuine wonder that women don’t murder more than men.

Next female thing: the eternal debate over clitoral versus vaginal orgasms. Kipnis reports on notable feminists who have weighed in on the dilemma, and the news is depressing. Doris Lessing regarded a man who offered clitoral orgasms as one in flight from intimacy. Simone de Beauvoir had neither the clitoral nor the vaginal kind with Sartre—so much for the theory of women becoming attached to men via the oxytocin released during orgasm. Beauvoir was attached as only a woman who hasn’t come can: with a vengeance.

Still, both Beauvoir and Germaine Greer found what the latter termed “digital massage” to be “pompous and deliberate,” subjugating women still further. (Receiving pleasure is, by definition, a submissive act—get with the program, girls!) On the other hand, Greer encouraged women to hold out not only for their vaginal orgasms but for “ecstasy.” “Sounds good—where do you sign up?” quips Kipnis. But remember, fingers will profit you nothing.

One of Kipnis’s overarching themes is, happily, not the old blame-patriarchy-for-everything theory but the enormous depths of “ambivalence among women themselves.” Some women, however, clearly try harder than others and subscribe to what Kipnis calls “emotional orgasms.” “There’s a name for someone,” she writes, “who would call that an orgasm: female.”

Female masochism again raises its head with the curious current practice of “hooking up,” where girls claim sexual “freedom,” while the boys enjoy a waking wet dream. As for this new romance—more accurately described as the blowjob-in-the-toilet encounter—Kipnis writes, “at least under the old femininity, you got taken to dinner.” Indeed, if this is female liberation, then give me death—or at least some decent “pompous and deliberate” digital subjugation. Wouldn’t feminism dictate just the opposite: the eat-me-then-get-out-of-my-bedroom romance? I’ll sign everyone up.

In “Envy,” Kipnis updates the eternal mystery of what women want (Freud, Freud everywhere, so much for our despair). There is always, she explains, something “invariably missing,” hence, the “underlying sense of female inadequacy.” The “Feisty Feminist,” she writes, “wanted to have what men have, without stopping to consider whether it was worth having.” Alternately, the “Eternal Feminine” looks like “an updated version of traditional femininity” and suggests that the “whole goddess-worshipping New Age veneer” has worn off. It is certainly difficult to imagine La Kipnis lighting incense and candles, toking up, and wafting about her sacred space chanting to Isis in an orange sequined caftan.

In the last essay, “Vulnerability,” Kipnis riffs on the most valuable and troublesome orifice in the world, the “small furry thing” she calls a “pootietang.” “Protecting that prized portal,” she observes, “is virtually the bedrock of female experience.” On the other hand, she suggests that “perhaps they’re overpriced,” rendering them more “theft-prone.” She thus segues to suggest that women should stop worrying about rape—their worry is way out of proportion to the statistical likelihood. Rape could really be “construed as an equal-opportunity form of victimization,” she suggests, somewhat sarcastically, and asks, What “prevents marauding gangs of criminally minded women from finding smallish men, holding them down, and penetrating them digitally [would Germaine Greer approve?]

or with other implements?” Dream on, Ms. Kipnis: One sees here an example of the author overreaching herself, swept away with ideas, language, and exasperation with her own sex, resulting in an insidious statement about a very serious subject. While enjoying the roller-coaster ride with Kipnis, occasionally one wonders about her real motives. Is she really just an intellectual show-off, a well-read performance artist, without real depth to her thoughts? Maybe. But wait, the loop-the-loop is not quite over.

My favorite chapter, “Dirt,” brings us back to the toilet-cleaner question, where Kipnis is on firmer ground. “Do women care,” she ponders, “a smidgen too much for cleaning?” “How will women ever really achieve social equality,” she writes, “when even a high-paid glass-ceiling-smasher corporate go-getter type somehow can’t stop herself from noticing what needs cleaning, thus winds up in the kitchen at two a.m. frantically scrubbing things?”

Meanwhile Kipnis offers the only practical advice in her stitch ‘n’ bitch book. On abrasive cleaners: “Soft Scrub rules.” I would like to add, in a girlfriendy kind of way, that Soft Scrub will scratch the hell out of your bathtub if you have just had the enamel refurbished. Kipnis is clearly closer to glass-ceiling smashing than most women, but I, for one, will happily bring my broom to sweep her broken glass and then contemplate my lack of ambition during a long, hot soak in my scratched, but very clean, bathtub.

Kipnis’s books offer a fascinating portrait of a woman dancing as fast as she can—with considerable grace, despite her Timberlands—around the miseries inherent in romantic love. For all her academic credentials—she is a professor of media studies at Northwestern University and the recipient of numerous fellowships and grants—one must be grateful that she has not squandered her anger in academic dryness. The Female Thing is, on the contrary, a virtual swamp.

So why is this passionate woman embedded in her Hummer on the front line of the war called love? Such pyrotechnic intellectualism about the least intellectual act in the world—fucking and its discontents—is revealing. Behind the bons mots and the clever observations, Kipnis reveals a certain contempt and superiority—in other words, a certain sadness. Laura Kipnis is in the end, I suspect, a true Romantic: disillusioned, shattered.

Hooray for her! She shows what a smart gal can do with disappointment and has, at least, put some energy into explaining it all for the rest of us. I am advised to offer a “full disclosure” here—my lucky day, I guess. Kipnis refers to my own addition to the genre of “obsessive female masochism,” in my book The Surrender, as being “infused with the ecstasy of public self-exposure.” I would like to add, to Kipnis’s felicitous assessment, that the “ecstasy” of publication not only paled beside the sex that inspired it but seriously interfered with my sex life—how’s that for masochism?

Kipnis, despite herself, has written yet another woman’s memoir—but one better, and more original, than most. One thing’s clear, Kipnis will only go down fighting. As for me, I’m now off to clean my toilet—with the lavender stuff. It’s a female thing called Progress.

Toni Bentley danced with Balanchine’s New York City Ballet for ten years. She is the author of five books, most recently, The Surrender: An Erotic Memoir (Regan Books, 2004).