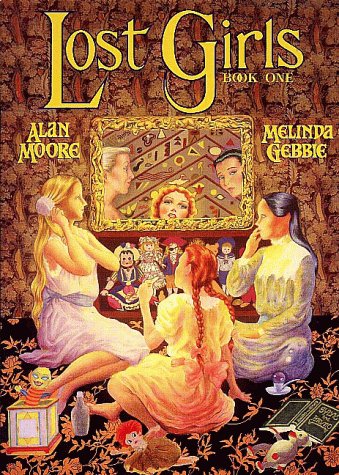

Comic-book writer Alan Moore, author of V for Vendetta, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and the much-lauded Watchmen, insists that his three-volume graphic novel, Lost Girls, be viewed as pornography—a provocative sound bite if ever I’ve heard one. Produced in collaboration with artist Melinda Gebbie, the oversize boxed set has been sixteen years in the making. During this period, it’s assumed mythic proportions, eagerly anticipated by some, reviled by others, assumed unpublishable by many.

There’s no denying the seductive brilliance of Moore’s writing. Like most American women, I’m a sucker for a literate Englishman, and Moore, a master of the language, is clearly in his element with this post-Victorian saga. Sadly, Gebbie’s artwork doesn’t live up to his sophisticated dialogue. Though her painstaking devotion to each panel is obvious and her colors are stunning, she simply can’t draw the human body with the expertise required for sexual stimulation. I kept wishing she’d examined more garden-variety pornography to see how the bits fit together, or at least called boyfriend Moore in to show her which end is up on the glans penis. Gebbie is better when mimicking the illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley and Franz von Bayros that appear in The White Book—a notorious collection of Victorian erotica that appears in Lost Girls—but a talent for imitation doesn’t make the best recommendation.

Lost Girls‘s central plot places the now-grown female leads from three well-known children’s books (Through the Looking Glass, Peter Pan, and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz) in a lush Austrian hotel on the eve of World War I. Alice, the oldest, is a decadent upper-class lesbian. Wendy is middle-class, inhibited, and unhappily married. Dorothy is the venturesome American farm girl. Inspired by The White Book, the three begin sharing their sexual histories, bodies, a few sexual appliances, and quite a lot of opium. Their tales, told in rotation, rework the original texts as stories of sexual awakening, with each character approximately the same age as in the original book—which is where things get a bit troublesome.

Pornography is held to a higher standard than is erotica. It can never beg creative license; content always counts. And while in my twenty-five years of making men’s magazines I never saw evidence that masturbating to a photo, painting, or thought leads to acting out what’s in that photo, painting, or thought, I still accept that there is forbidden territory in the business of selling lust. Moore has some reputation as a provocateur and rule breaker, so perhaps it’s no surprise he’s taken on society’s top taboo. The charitable spin is that he and Gebbie are trying to defuse the hysteria over child pornography by allowing readers to confront the subject in a safe fantasy environment. In our frenzy to protect innocence, we forget that sexual curiosity exists from birth and that most girls willingly lose their virginity before age eighteen. Moore even has the hotel’s owner remind us that the images in The White Book, and by implication those in Lost Girls, are just fantasies. “Fiction and fact,” he observes, “only madmen and magistrates cannot discriminate between them.” Moore is right, but he also pokes those magistrates with a pretty big stick when the hotel owner goes on to confess, “I was a forger, many years ago. A very bad man, living in Paris with a boy and a girl. . . . Th–they were children of two whores I knew. Perhaps they were even mine. What a time I had! Every day I would fuck them both, or draw them fucking each other. My cock made art.” Perhaps it did, but this dialogue, which develops more graphically on the following page, as well as the accompanying illustrations of prepubescent children servicing “drunk sailors,” will probably not pass as art for any but the most ardent fans—and the odd pedophile. In a recent interview, Moore stated, “If we wanted to talk honestly about pornography, we had to include all of it. . . . We couldn’t brush anything that was currently socially uncomfortable under the carpet, because that would not have been being true to the idea behind the work.” In fact, there are a great many facets of pornography not included in this work, but I suspect what is contained within its pages will be of far greater concern to madmen, magistrates, and the average reader alike.